How to Prevent Hypertension from Ruining Your Health

Imagine being diagnosed with a disease that you don't have, taking multiple prescription drugs that you don't need, and experiencing side effects that require you to take even more drugs. Then imagine that almost everyone past 50 is diagnosed with the same fake disease, and what it does to their health. Impossible, right?

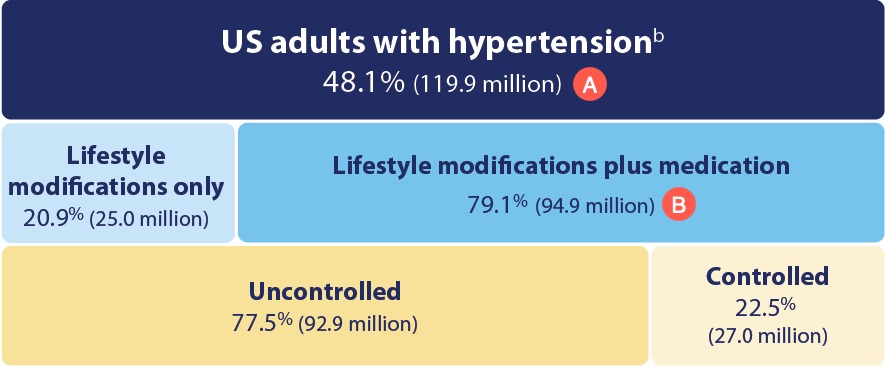

It's very possible, actually. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 119.9 million (A) adults in the United States have been diagnosed with high blood pressure, all of them were advised to modify their lifestyle, and 94.9 million (B) were prescribed medication [link]:

This epidemiological statistic sounds fishy because in 2025, approximately 124 million Americans were 50 years and older. If you take the CDC number of 119.9 million "US adults with hypertenson" at face value, it implies that almost everyone over 50 has one.

That conclusion does not hold up because population-level disease rates never approach total saturation. Even the most common age-related conditions, such as insomnia (up to 48%) or arthritis (54%), do not come close to affecting nearly every individual in an entire age group.

When disease numbers approach total saturation range, it means the diagnostic criteria were set so low that normal physiology is being labeled as pathology.

Here is how and why this made-up crisis emerged:

The Anatomy of the Made-up Medical Crisis

Blood pressure values in healthy people naturally fluctuate throughout the day from posture, activity, stress, food and fluid intake, caffeine, alcohol, time of day, exercise, and a number of other factors.

Both systolic (upper) and diastolic (lower) values can vary 10 to 20 mmHg in both directions. These fluctuations are considered normal unless they are extreme or permanently outside standard ranges.

In practice, it means the following: if a 120 over 80 reading is considered a normal blood pressure, then 140 over 100 under physical or emotional stress is normal too, and so is 100 over 60 while at rest.

I am not making this up to fit my narrative. This information came from an article written by Dr. Amy Scanlon, MD, FACC, who "...frequently lectures and participates in speaking engagements for the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology:"

In healthy individuals, blood pressure can vary by 10–20 mmHg throughout the day. These short-term fluctuations are generally harmless and reflect the body's response to different stimuli and activities [link].

It is equally important to keep in mind that a sporadic elevated blood pressure during intense load by itself is not going to harm healthy and well-trained individuals:

A large study on consecutive Italian Olympic Athletes examining blood pressure adaptation to exercise stated that the upper normal values of blood pressure during maximal exercise testing are 220/85 mmHg in male and 200/80 in female athletes. [...] ...during weightlifting, BP can even temporarily rise to levels of as much as 480/350 mmHg [link].

It also means that when you exercise in the gym on the advice of your doctor, your blood pressure can easily rise above 140–160 mmHg, but no doctor will tell you to stop exercising unless you have some rare condition that would not allow you to exercise in the first place.

The Origins of the Swindle

When you measure your blood pressure right after waking up, it should be below or around 120 over 80 for most healthy people, regardless of age. This measurement is called basal blood pressure.

Another related term is resting blood pressure, which is taken at any time during the day when a person is at rest and taken after sitting quietly for 5 to 10 minutes.

Now, imagine with me that on the same day, you visit a doctor for an annual physical. You drive to the clinic, park your car, take the elevator, check in at the front desk, sign a stack of forms, then spend 20 to 30 minutes in a cold waiting room for your turn as your anxiety builds.

Finally, you're brought into the examination room, asked to undress, and perched on the exam table. The nurse takes your blood pressure, records 135 over 85, and passes the chart to the physician. She glances at the chart, frowns slightly, and says:

"You have high blood pressure. Let me check it one more time to make sure the reading was correct."

Hearing that, already anxious, your mouth dries up from fear, and you feel even more anxious. The physician does another measurement, and this time it is 140 over 90. She frowns again:

"It’s still high. We definitely need to put you on medication. You don’t want to have a heart attack or a stroke, do you?"

"No, doctor, I don’t. My kids are still in high school…"

"Well, this is serious. We'll take a blood test to check your cholesterol. If it’s high too, we'll put you on a small dose of statins to keep it under control."

"Thank you, doctor!"

"I recommend you cut out red meat, salt, and animal fat. You should eat more fiber, fresh fruits and vegetables, and drink eight glasses of water. And start exercising to drop some weight."

"Sorry, doctor, I don't have time for exercise with my job and two kids."

"In that case, I recommend taking Wegovy. I hope your insurance will cover it."

"Thank you, doctor, I hope it will!"

"To be on the safe side, I'll write you a prescription for two first-line blood pressure medications to keep yours under control. One is a diuretic to reduce the amount of fluids in the body, and the other is to relax your blood vessels. Both are well tolerated by people your age. If your cholesterol is high, we'll call you and send the prescription to your pharmacy. Would you like me to prescribe Wegovy now?"

And that's how it goes. You came for a routine check instead of lunch, hungry, anxious, and fearful. You got stressed even more by the wait, by the cold, by the undressing, by the anticipation, and by the intimidating and stern doctor.

Naturally, your blood pressure went up from all of the above, plus caffeine from morning coffee and elevated insulin from hunger, and you got bulldozed into taking two prescription drugs, each with a list of side effects longer than this introduction, and potentially two more.

Why two drugs for hypertension right away? It's what the protocol says:

Most patients require ≥ 2 medications as treatment of hypertension often starts late in the course.

When combination therapy with 2 antihypertensive agents is selected, options include either an ACE inhibitor or ARB combined with either a diuretic or a calcium channel blocker.

Treatment for Hypertension; The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, Professional Edition [link]

A similar scenario plays out with minor variations in practically every medical office across the United States daily, even though it violates all established protocols for diagnosing hypertension.

It happens because clinics and hospitals (which nowadays own most of the clinics) are incentivized by pharmaceutical and insurance companies to convert healthy people into lifelong patients dependent on drugs and treatments instead of addressing the root causes of their elevated readings.

I am sure many of you are saying to yourself — he is making all this up to advance his agenda. No, I am not. Here is a description of the hypertension diagnosing protocol from the same Merck Manual, the "gold standard" for the US-based physicians:

Multiple measurements of BP are needed to confirm hypertension because of the inherent variability of blood pressure. Blood pressure typically fluctuates with time of day; in classic diurnal [recurring daily – KM] variation, BP is higher by day (especially in the morning) and lower by night [link].

I highly recommend that you tap the link and read the entire "Diagnosis of Hypertension" section, and ask yourself: "Have I ever been examined like it suppose to be?"

Not likely, unless you are a patient of a concierge clinic for the ultra-rich that employs doctors who are incentivized to keep you off drugs for as long as possible because their income doesn't depend on payments by insurance companies.

That is why practically anyone past fifty can be "diagnosed" with "high blood pressure" under similar circumstances, and this condition is labeled as "primary" or "essential" hypertension. Not surprisingly, up to 95 percent of all diagnoses fall into this classification.

For context, the clinical definition of the remaining 5 percent is described by Dr. Scanlon, whom I cited earlier:

Consistently high blood pressure readings (140/90 mmHg or higher) indicate hypertension, which increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other health problems [link].

Please note her choice of words: not "occasionally high," but "consistently high," and above 140 over 90. That is "real" hypertension, the one that "increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other health problems," not the one that pads the pockets of clinics, hospitals, insurers, and pharmaceutical companies.

This pattern isn't an accident but the inevitable byproduct of industrialized medicine built on perverse financial incentives to maximize income, growth, and profit by converting healthy people into chronic patients.

So let's take a closer look at the most common myths that keep this cycle going.

Nothing Good Happens When Medical Myths Become the Standard of Care

Let me remind you that I am not a medical doctor but a medical writer with a pharmacist's education and research experience in forensic nutrition. This section is about the side effects of hypertension drugs and treatments that are clearly described in the Prescription Information pamphlet that must accompany every drug.

None of what you are about to read here is my malicious fantasy or an attempt to convince you not to take prescribed medications. I simply interpret the facts as I see them and share my interpretation with you.

If you still have doubts, I strongly encourage you to copy and paste any of my statements into ChatGPT, Perplexity, Gemini, Claude, DeepThink, or any other AI chatbot and ask: "Is this information factual and truthful?"

And if you are already taking medication, do not stop it on your own because sudden withdrawal may be harmful. There are plenty of medical doctors in integrative and alternative practices who will be more than happy to assist you in deprescribing them safely and responsibly if you were misdiagnosed under the circumstances I described earlier.

Please note that you may find a small degree of repetition in the sections below because I need to provide full context while describing different situations.

Here we go:

Myth #1. All types of hypertension are equally bad and dangerous

Most people hear the word "hypertension" and assume a fixed, permanent, and chronic condition. In reality, most people move in and out of the hypertensive range as habits and health change. The 'chronic disease' label often persists even after the cause fades. The classification of hypertension confirms my reasoning:

-

Primary (essential) hypertension. Most common, accounting for about 90–95% of cases. There is no identifiable single cause; instead, it results from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

-

Secondary hypertension. Caused by an underlying medical condition such as kidney disease, hormonal disorders (e.g., adrenal gland dysfunction), obstructive sleep apnea, certain medications, or congenital heart defects. This is less common, accounting for about 5–10% of cases.

-

Isolated systolic hypertension. Elevated systolic pressure with normal diastolic, especially common in older adults with preexisting arterial stiffness.

-

Resistant hypertension. Blood pressure remains high despite the use of multiple antihypertensive drugs.

-

Malignant hypertension. A severe, rapidly progressive form causing organ damage and requiring immediate treatment.

Blood pressure fluctuates throughout the day because of posture, meals, salt intake, water intake, temperature, stress, sleep depth, pain, and physical load. Every one of these factors can raise or lower the number by a wide margin within minutes. This is normal physiology. It means that a single reading in a clinic tells you nothing about a person’s true state.

The only objective measure is basal blood pressure. Basal pressure is the level the body settles into when nothing pushes it up or down. You see it early in the morning, after a full night of sleep, before food, caffeine, or activity. It reflects real vascular tone, real volume status, and real autonomic balance. It is as close as you can get to the body’s baseline without interference.

Basal pressure has two qualities that clinic readings lack. First, it is repeatable. If the number is real, you will see the same pattern across several mornings. Second, it tracks long-term risk far better than random office readings because it records the state of the system, not the noise around it.

Every other number during the day is a reaction to something. Basal pressure is the only number that represents the actual condition. Without it, the diagnosis of hypertension rests on guesswork, not physiology.

For these reasons, most cases of primary hypertension are misdiagnosed because the diagnosis depends on a single number taken under artificial conditions. A clinic is the worst place to judge a person’s true blood pressure.

People walk in stressed, rushed, stressed out, or sleep-deprived. White coat hypertension affects up to a third of patients in some groups, but it still gets labeled as “primary” as if it were a chronic disease. Cuffs are often the wrong size. Nurses take one quick reading with no rest and record it as fact. This alone creates tens of millions of false cases of “primary hypertension.”

So, if you receive a diagnosis of hypertension from a single office reading without confirmation through basal blood pressure measured at home in the early morning over several days, the diagnosis is false. It does not reflect your real state and does not meet the standard for an objective assessment.

The other four types of hypertension — secondary, isolated systolic, resistant, and malignant — represent around 10% of the remaining cases and are serious medical conditions that require full attention and treatment by the best cardiologist you can find.

Myth #2. Drug therapy for primary hypertension is safe and effective

Contemporary hypertension treatment relies on six principal drug classes: thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. A direct renin inhibitor (aliskiren) is also available, although it is used far less often. Diuretics remain central because they lower plasma volume and, in turn, reduce blood pressure by increasing the excretion of water through urination.

Although these drug classes use different primary mechanisms, they all converge on the same physiological targets that determine blood pressure: the strength and rate of the heart's contraction, the tone of vascular smooth muscle, and the volume of blood in circulation. Some act directly on the heart or blood vessel walls, while others work indirectly by altering kidney handling of salt and water or by modifying hormonal signals such as the renin–angiotensin system:

-

Beta-blockers slow the heart rate and reduce the force of each heartbeat. With the heart working less aggressively, blood pressure drops. Beta-blockers are considered "legacy drugs" and are rarely used at present.

These are the most commonly prescribed beta-blockers for hypertension as well as heart failure and arrhythmias: Metoprolol (Toprol XL, Lopressor), Carvedilol (Coreg), Atenolol (Tenormin), Propranolol (Inderal LA), Bisoprolol (Zebeta).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: blurred vision, chest pain or discomfort, confusion, dizziness, faintness, or lightheadedness when getting up suddenly from a lying or sitting position, slow or irregular heartbeat, sweating, unusual tiredness or weakness [drugs.com].

-

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) relax the muscle in the walls of arteries by limiting calcium flow into those cells. Relaxed arteries open wider and allow blood to move with less resistance.

The most widely prescribed CCBs for hypertension, angina, and heart rhythm disorders are: Amlodipine (Norvasc), Diltiazem (Cardizem, Tiazac), Verapamil (Calan, Verelan), Felodipine (Plendil), and Nifedipine (Procardia).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: chest pain or discomfort, fast or irregular heartbeat, nausea or vomiting, pain or discomfort in the arms, jaw, back, or neck, trouble breathing, or sweating, pain or tenderness in the upper stomach, pale stools, dark urine, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, or yellow eyes or skin [drugs.com].

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors block the formation of angiotensin II, a hormone that normally tightens blood vessels. With less of this hormone, vessels stay more relaxed and pressure decreases.

The most commonly prescribed ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, heart failure, and other cardiovascular conditions are Lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril, Qbrelis), Enalapril (Vasotec), Benazepril (Lotensin), Ramipril (Altace), Captopril (Capoten).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: blurred vision, cloudy urine, confusion, decreased urine output or decreased urine-concentrating ability, dizziness, sweating, unusual tiredness or weakness, faintness or lightheadedness when getting up suddenly from a lying or sitting position [drugs.com].

-

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) prevent angiotensin II from attaching to its receptors on blood vessels. This keeps the vessels from tightening and helps maintain lower pressure.

These ARBs are widely used to treat hypertension, heart failure, and kidney protection, with Losartan being the most commonly prescribed: Losartan (Cozaar), Valsartan (Diovan), Olmesartan (Benicar), Telmisartan (Micardis), Irbesartan (Avapro).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: blurred vision, burning, crawling, itching, numbness, prickling, "pins and needles", or tingling feelings, confusion, difficult breathing, dizziness, faintness, or lightheadedness when getting up suddenly from a lying or sitting position, fainting, fast or irregular heartbeat, nausea or vomiting, nervousness, numbness or tingling in the hands, feet, or lips, stomach pain, sweating, unusual tiredness or weakness, weakness or heaviness of the legs [drugs.com].

-

Direct renin inhibitor (aliskiren) interrupts the hormonal chain that produces angiotensin II at its earliest step. By slowing this cascade, it reduces vessel tightening and helps lower blood pressure.

Currently, Aliskiren is the only widely approved and marketed direct renin inhibitor used to treat hypertension, with several combination products like aliskiren/amlodipine (Tekamlo) and aliskiren/valsartan (Valturna).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: body aches or pain, chills, cough, diarrhea, difficulty with breathing, ear congestion, fever, headache, loss of voice, nasal congestion, runny nose, sneezing, sore throat, unusual tiredness or weakness [drugs.com].

-

Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics lower blood pressure by forcing the kidneys to release more salt and water with urine. This action reduces the amount of fluid in the bloodstream, which lowers pressure inside the vessels. At present, diuretics are considered the first line of defense for hypertension.

The most commonly prescribed diuretics for hypertension and edema management are Hydrochlorothiazide (Microzide, HydroDIURIL), Chlorthalidone (Thalitone, Hygroton), Indapamide (Lozol), Chlorothiazide (Diuril), Metolazone (Zaroxolyn).

The most common precautions and side effects for this class of drugs are: dizziness, seizures, decreased urine, drowsiness, dry mouth, excessive thirst, increased heart rate or pulse, muscle pains or cramps, nausea or vomiting, unusual tiredness or weakness, blurred vision, difficulty in reading, eye pain, and increased risk of getting skin cancer [drugs.com].

All of the above medications are considered systemic because they act throughout the entire body rather than only the arteries, heart, or kidneys.

The systemic nature of these drugs is central to understanding their drawbacks. Even though they work through different mechanisms, none of them can limit their effects to blood pressure alone. Once in circulation, they interact with tissues and organ systems that rely on the same receptors, enzymes, fluids, electrolytes, or smooth muscle responses.

The challenge is that they cannot distinguish these tissues from the smooth muscle in the urethra, uterus, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, or any other organ that depends on the same muscle type. Once they enter the bloodstream, their relaxing effect extends to every system that uses smooth muscle:

-

For the stomach, it means reduced muscle activity that causes indigestion, delayed emptying, heartburn, peptic ulcers, infections, and food poisoning.

-

For the gallbladder, it means weaker contraction that promotes bile stasis, gallstone formation, malabsorption of essential fats, and eventual gallbladder removal surgery.

-

For the small intestine, it means disrupted motility that can lead to fermentation, gas-related cramps, bloating, inflammation, malnutrition from poor assimilation, and obstruction.

-

For the colon, it means irregular muscle tone that results in diarrhea, constipation, or fecal incontinence.

-

For the male and female urethra, it means weakened sphincter control that can cause urinary incontinence.

-

For the uterus, it means reduced smooth muscle responsiveness that can affect menstrual cramping, pelvic tone, and the muscular contractions involved in orgasm.

-

For the prostate gland, it means impaired smooth muscle contraction that can delay orgasm, interfere with ejaculation, create fluid congestion in the seminal tract, and produce symptoms that feel similar to prostate enlargement, including pressure, incomplete bladder emptying, and frequent urination.

-

For other smooth-muscle organs, it means similar problems wherever coordinated muscle activity is required.

I hope you also noticed that dizziness, faintness, seizures, drowsiness, blurred vision, and confusion are common to most of these drugs, but you are still legally fit to drive a car, fly a plane, steer a ship, run a freight train, or operate heavy machinery, albeit with "normal blood pressure."

Myth #3. Drug therapy for hypertension prevents strokes and heart attacks

Nothing can be further from the truth, according to the numerous randomly controlled trials (RCTs) run to investigate the effectiveness of the hypertension treatments.

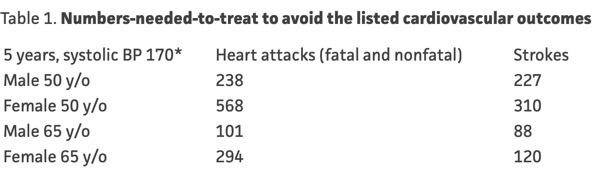

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) indicates how many people must take medication for a certain period for one person to benefit, while the others receive no measurable benefit or may experience harm.

For hypertension, these figures are [link]:

In other words, 238 men and 568 women with an already very high systolic blood pressure (above 170 mmHg) had to take medication for 5 years to prevent one heart attack.

According to the same source, 1 in 10 patients were harmed from medication side effects while taking it or after stopping the drug [link]. Wrap your head around this: 23 men and 56 women were harmed by taking blood pressure medication to prevent a single heart attack, and 22 men and 31 women were harmed to prevent a single stroke.

Even more damning is the following quote:

It is also notable that not all drugs that lower BP lead to benefits. Atenolol, doxazosin, and aliskiren all lower blood pressure but large RCTs have shown no heart attack, stroke, or death benefit from these agents when used to lower blood pressure. Moreover, evidence for lowering BP below 150 (systolic) with any agent has not been beneficial in trials, but does increase harms [link].

The article also adds:

Harms of BP medications are very real, but not as well documented in trials as benefits. Roughly 10% stop a drug due to intolerability (NNH* 10) and types of side effects vary between antihypertensive classes, including some that can be severe (angioedema, syncope, arrhythmias, electrolyte disturbances, etc.) [link].

If you have not checked the links, I want to point out that the article was published on July 21, 2024, written by Dr. James McCormack, MD, and peer-reviewed by Dr. Rita Redberg, MD, and Dr. Barbara Roberts, MD.

In this Guide, I am talking almost exclusively about people with primary or misdiagnosed hypertension that is slightly above 140 mmHg, way below 170 mmHg in the NNT analysis above.

Myth #4. Salt Raises Blood Pressure in Healthy People

It is one of the most preposterous and harmful myths about hypertension in healthy people for the following reasons:

The word "blood" in the phrase "blood pressure" refers to a 0.9% salt (NaCl) solution made of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) ions. Salt keeps fluid volume stable in the blood, lymph, inside the cells, and Interstitial fluid (in the space between cells). Technically speaking, your body swims in brine, which comprises 60% to 65% of your body weight.

When the intestines move salt into the bloodstream, the body pulls in water to reduce its concentration to normal.

In theory, this could raise blood pressure because the cardiovascular system is a closed loop, and blood vessels can expand only to a point to accommodate a larger volume of blood plasma. After that point of no more expansion, the blood pressure would go up, and up, and up.

In practice, this theory falls apart once you look at how the body handles excess volume of blood plasma. It has fast control systems that shift excess fluid into the stomach and colon. These systems act long before blood pressure can climb to a harmful level.

The belief that salt raises blood pressure came from people who ignored these basic control systems. The result was a claim that never matched real physiology. It pushed hundreds of millions into low salt diets that did not match human needs or biology.

In turn, a low salt diet forces a sharp rise in renin (kidney-regulating enzyme) and aldosterone (salt-regulating hormone). In many people, this creates higher blood pressure, not lower. Here is how this works:

Low salt reduces blood volume slightly to maintain a 0.9% ratio of salt to plasma. The kidneys sense this drop and release more renin. Renin sets off a chain of reactions that produces angiotensin II, a blood pressure control hormone. Angiotensin II narrows blood vessels and raises blood pressure. It also signals the adrenal glands to release aldosterone.

In turn, aldosterone causes the kidneys to hold more salt and water. The body tries to restore normal volume, but the vessels that constricted under angiotensin II stay tight. Now there is more fluid in the system and tighter vessels at the same time. That combination drives blood pressure up.

This process also triggers a long list of chronic disorders that do far more harm than a brief rise in pressure ever could. I cover those disorders in detail in my guide titled 44 Serious Disorders Caused by Salt Deficiency.

The current Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for salt per day for adults is 6 grams of salt. That's one level teaspoon daily and the same amount as 2300 mg of sodium. The RDA represents a survival minimum, not a killer dose.

This myth doesn’t apply to people with renal or advanced cardiovascular diseases, whose ability to regulate sodium and fluid is already impaired and who require individualized medical management.

Myth #5. Exercise helps to reduce blood pressure

Exercise supports general health, but it's not a primary tool for blood pressure control. Most long-term reduction that people credit to exercise comes from weight loss, better sleep, and lower stress, not from the activity itself.

Moderate exercise can reduce blood pressure in some adults, but the size of that drop is modest and brief. Heavy exercise, on the other hand, can drive pressure up for several hours because the heart works harder and vessels tighten to support higher output.

The irony of this advice is that a clinical stress test imitates medium-intensity exercise, such as a fast walk. The goal is to see how high the pulse rate and blood pressure will rise under load. The rise is expected and often sharp:

Exercise-induced hypertension (EIH) is defined as elevated blood pressure (BP) > 190mmHg for females and > 210 mmHg for males during exercise. EIH is prevalent among athletes and healthy individuals with no cardiovascular (CV) risk factors [link].

Medical offices that run these tests must, by law, have the room accessible to an ambulance stretcher because it can trigger a heart attack or a stroke.

Exercise represents a major risk for people who take blood pressure medication along with a low salt diet. The drug effect, combined with sweat loss, can cause a sharp drop in blood pressure. The hot shower or sauna can further exacerbate this problem. Many people in this state faint and fall, often with serious injuries.

The risk is even higher for people who take medication that lowers blood sugar because it adds another path to faint. Hypoglycemia can strike fast during exercise with no time to react or protect the head during a fall.

All of the above factors combined are even more dangerous while driving from the gym.

I am absolutely pro-exercise, but not for someone who has been diagnosed with high blood pressure and goes into it unprepared or under the influence of multiple medications to lower blood pressure and blood sugar.

When Treatment Is Worse Than the Disease

When a family doctor writes you a prescription for an antihypertensive drug, they mean well and probably do the same for themselves and their family members. In other words, they aren't villains but the same unwitting victims as their patients. But that doesn't mean that you should be a victim too.

Let's go into this subject in more depth because no matter how "innocent" these drugs may seem, they come with life-changing side effects that can finish you long before a heart attack or stroke.

Feeling tired, depressed, anxious, and nervous

These reactions are well-established side effects of hypertension drugs because low blood pressure impacts the systems that regulate energy, mood, and emotional balance.

Cumulatively, these changes are enough to strain a marriage, damage friendships, and derail a successful career. Even worse, when you return to the same doctor, the likely response is another prescription for a strong antidepressant or antianxiety drug that will only intensify the very problems that brought you in.

Dizziness, drowsiness, and fainting (syncope)

These side effects result from a lack of well-oxygenated blood reaching the brain, or hypoxia. This condition is behind countless car accidents, accidental falls, and resulting bone fractures. It is especially dangerous for captains, pilots, train conductors, crane operators, commercial drivers, nuclear plant engineers, military officers, and others in similar high-risk occupations.

In many respects, these side effects are no different from being drunk or high on narcotics, and they are equally dangerous. Nonetheless, if a police officer stops you for erratic driving and you pass the sobriety test, you are free to continue driving and risk injuring yourself and others with complete impunity.

Insomnia, poor quality of sleep, and wild dreams

Sleeping problems linked to hypertension drugs make all of the above conditions worse. The risk escalates when sleeping aids are added because the combination can intensify nighttime breathing problems and lead to severe next-day drowsiness. These effects contribute to traffic accidents, errors at work, and costly career mistakes such as dozing off during meetings.

Many antihypertensive drugs can cause sleep problems. Beta-blockers are well known for insomnia, vivid dreams, and sleep fragmentation from reduced melatonin secretion. CCBs, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics can also disrupt sleep through nighttime urination, or cough (ACE inhibitors).

Cardiac arrest or respiratory failure during sleep can occur when taking sedatives and antihypertensives at the same time. Either condition ends in death.

Severe migraine headaches

When blood vessels are artificially relaxed or constricted by medication, the sudden shifts in intracranial blood flow can activate the same pain pathways involved in classic migraines. Reduced brain perfusion deprives parts of the brain of oxygen, while blood vessel dilation can overstimulate the nerve system behind migraine attacks.

Some people also experience visual disturbances, light sensitivity, nausea, or a pulsating pain behind the eyes or temples. The effect is especially common in people with a history of migraines, hormonal sensitivity, or chronic stress.

In many cases, the headaches appear shortly after the dose is increased or when two or more blood pressure medications are combined. The medication may reduce the blood pressure levels, but the effect on the brain can cause migraine episodes more often than before treatment.

Persistent cough, sore throat, hoarse voice, and difficulty breathing and swallowing

These problems are most often associated with ACE inhibitors, which can trigger a persistent cough and irritation of the throat. ACE inhibitors and ARBs can also cause episodes of edema that lead to swelling, hoarseness, or trouble breathing and swallowing.

Most of these symptoms resolve after the medication is discontinued. These effects are especially damaging for people in professions that require continuous verbal communication, such as teaching, sales, and acting.

Sinus congestion and a runny nose

Some hypertension drugs, particularly ARBs, list a runny or stuffy nose among their known side effects. The exact mechanism is not fully established, but these medications can contribute to nasal symptoms in a noticeable minority of users.

On the surface, this seems trivial compared to the risk of a heart attack, yet the trouble starts when sinus pain develops and people turn to oral decongestants or NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen. These drugs are systemic and are known to raise blood pressure or interfere with blood pressure control, so the fix often leads to a new round of problems.

Weight gain, pre-diabetes, and type 2 diabetes

Older beta blockers and thiazide diuretics can promote weight gain and worsen blood sugar control. Over time, this pattern contributes to obesity, pre-diabetes, and type 2 diabetes, which in turn accelerates atherosclerosis and heart disease.

Once diabetes is diagnosed, patients are placed on glucose-lowering medications that often add more weight or fluid retention of their own, creating a metabolic loop that works against long-term cardiovascular health even while the drugs keep blood pressure numbers in range.

Swelling of the face, abdomen, ankles, and feet

Some blood pressure drugs, particularly calcium channel blockers, can cause fluid retention and visible swelling, most often in the lower legs and ankles. This condition occurs when arterioles widen but veins do not, raising blood pressure in the small vessels and forcing fluid into surrounding tissues. ACE inhibitors and ARBs may also cause facial swelling known as angioedema through a different mechanism. In both cases, the problem results from reduced vascular tone.

Dry mouth (xerostomia)

This unpleasant condition promotes bad breath, oral ulcers, tooth decay, gum disease, and eventual tooth loss. Saliva helps protect the mouth and upper airways from infection, so its deficiency increases vulnerability to oral candida, colds, and other respiratory pathogens.

All types of diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and low salt diets reduce saliva production and thicken its consistency. Calcium channel blockers can also cause gum swelling, which can complicate chewing and oral hygiene.

Altered sense of taste and smell

Distortions in taste or smell (dysgeusia and hyposmia) are common with ACE inhibitors and some diuretics. These changes can reduce appetite and alter food preferences, often leading people to consume more carbohydrates and highly processed foods that are easier to eat and digest.

Hyperkalemia (high potassium level)

This potentially life-threatening condition occurs most often with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and potassium-sparing diuretics, especially in people with kidney disease or diabetes. These drugs reduce the body’s ability to excrete potassium, allowing it to build up in the blood.

A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and juices that are heavily encouraged for heart health and blood pressure prevention, can worsen the problem by adding more potassium from food sources.

Symptoms include muscle weakness, tingling of the hands or lips, irregular heartbeat, and shortness of breath. If left untreated, hyperkalemia can lead to cardiac arrest and death.

Diarrhea or severe vomiting

While not common side effects of blood pressure drugs, persistent diarrhea or vomiting can rapidly deplete fluids and electrolytes. In people taking ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or diuretics, dehydration increases the risk of low blood pressure, kidney strain, and dangerously high or low potassium levels. Even mild illness can become hazardous in this setting, since the combination of fluid loss and medication can trigger sudden weakness, fainting, or arrhythmia.

Digestive disorders

Calcium channel blockers and some beta blockers relax the smooth muscles of the stomach and intestines, slow peristalsis, and promote reflux, bloating, and constipation. Low salt diets exacerbate these problems even more because salt is essential for producing gastric acid and water retention in stool.

Diuretics, by contrast, disrupt digestion indirectly by reducing fluid availability and washing out electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and chloride. These changes can dry out the intestinal lining, weaken muscular contractions, and contribute to indigestion, heartburn, and constipation.

Erectile dysfunction

Adequate erections depend on healthy blood flow, which certain blood pressure drugs can impair. Older beta blockers and thiazide diuretics are the most common culprits, while ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and calcium channel blockers rarely cause this problem.

Some men take H2-blockers such as cimetidine for heartburn relief, unaware that this drug can further suppress sexual function by interfering with testosterone metabolism. The combined effect of vascular and hormonal changes can lead to reduced libido, weaker erections, and delayed orgasm.

Menopausal complications

Some blood pressure drugs can worsen symptoms commonly associated with menopause, such as flushing, fatigue, or reduced sexual desire. Calcium channel blockers may cause facial flushing, while beta blockers can interfere with libido or orgasmic function.

Although these effects don’t cause menopause or hormonal changes, they can intensify discomfort in women already experiencing menopause and strain emotional well-being, which in turn may exacerbate stress-induced hypertension.

Urinal incontinence

Hypertension drugs relax the tonus of the internal and external urethral sphincters — the muscles that control the flow of urine. When diuretics are added to the mix, this condition becomes a verifiable disaster. Both genders are equally affected by this complication.

Shockingly, urinary incontinence affects every second woman after 65, and I am guessing that hypertension drugs play a substantial role in this unfortunate situation.

Contrary to a common misconception, the urethral sphincter muscles in men are no stronger than in women. Men are less prone to urinary incontinence because of anatomical differences (longer urethra, larger bladder, less intra-abdominal pressure), pregnancy/childbirth after-effects in women, and hormonal factors that disproportionately affect the female pelvic floor muscles.

Premature aging

Long-term use of certain blood pressure drugs can intensify the visible and functional signs of aging by interfering with circulation, digestion, and nutrient metabolism.

Beta blockers may reduce peripheral blood flow and oxygen delivery to the skin, promoting dullness and hair thinning.

Diuretics accelerate fluid and electrolyte loss, contributing to dry skin, fatigue, and muscle weakness.

Calcium channel blockers and ACE inhibitors can impair oral health through gum swelling or dryness, while nutrient depletion from diuretic therapy increases the risk of bone and joint degeneration.

Over time, these combined effects create the appearance of accelerated aging, reduced vitality, slower recovery, and cognitive decline.

Side Effects From Diuretics

Diuretics reduce circulating blood volume, so the heart has a lesser volume of blood to push forward. It works, but the risks and complications from this brute-force approach are often more immediate and more disruptive than those from other antihypertensive drugs.

These risks compound even more when diuretics are combined with low-salt diets. Sodium, an essential electrolyte, is critical for fluid balance. If you don't have enough sodium in the body, you can drink as much water as you swallow, but the body cannot retain it.

Practically all of the complications from diuretics stem from three outcomes of volume and electrolyte loss: reduced blood volume, abnormal potassium levels, and allergies to sulfonamide-based diuretics. These complications include:

-

Frequent urinations are not a side effects but the intended outcome of taking diuretics. They force water out of the blood through the kidneys. Constant urination is especially disruptive for people who work outdoors or do not have immediate access to a bathroom. It also ruins nightly sleep, adding to stress and anxiety during the day, and drives blood pressure higher.

-

Nausea, vomiting, and digestive upset occur when rapid shifts in sodium, potassium, or magnesium interfere with normal muscle and nerve function in the stomach and intestines. The problem is not water being “pushed” into organs, but the direct effect of electrolyte imbalance on the digestive tract. The result is further dehydration and further loss of electrolytes. When this spiral begins, calling 911 is the safest option because IV fluids, electrolytes, and glucose are needed immediately.

-

Blurred vision, confusion, inability to sweat, and restlessness are classic signs of significant dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Once symptoms reach this point, drinking water is rarely enough to reverse the process. Medical intervention is the only safe response.

-

Muscle cramps and weakness stem from deficiencies in potassium, calcium, or magnesium caused by diuretics. They can be worsened by other medications such as antihypertensive drugs, statins, or antidepressants. Arrhythmias are common when potassium levels shift too far in either direction and can lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

-

Skin rash and hives result from severe allergic reactions to sulfonamide-based diuretics in susceptible people. Rare but documented complications include acute liver failure, agranulocytosis (collapse of white blood cells), hemolytic anemia (destruction of red blood cells), thrombocytopenia (loss of platelets), and Stevens–Johnson syndrome, a life-threatening condition in which the upper layer of skin separates from the lower layer.

-

Breast enlargement in men and women, fever, sore throat, cough, ringing in the ears, unusual bleeding or bruising, and rapid weight loss are classified as minor side effects. Some people may even see the rapid weight loss or breast enlargement as a bonus. That assumes, of course, they stay alive long enough to enjoy the results.

The real absurdity behind diuretics is this: if you want to reduce the amount of water in your body, simply reduce fluid intake for a short time. A healthy person naturally loses close to a liter of water a day through breathing, sweat, urine, and stool. Instead, people are told to drink eight glasses of water on top of the fluids already in their diets and then take diuretics to force the same water back out.

Surprised? Shocked? Disappointed? Angry?

Actually, there are even more side effects listed in the Prescription Information booklets. Please look them up for the drugs that were prescribed to you.

It is also very likely that after a short while, your body will auto-adapt to drugs to compensate for inadequate blood pressure, and when you go to see your doctor for the next checkup, she will dutifully prescribe a more potent drug, and the cycle repeats, except with more potential problems.

The perils of blood pressure becoming too low

When your blood pressure drops below about 90 over 60 mmHg, you enter a state called hypotension. It is far more dangerous in the short term than hypertension because the body depends on adequate blood pressure to deliver oxygen and nutrients to the vital organs.

The results are dizziness, fainting, confusion, blurred vision, or sudden loss of consciousness. A severe drop can interrupt cerebral perfusion and trigger a stroke, or cause an unstable heart rhythm and lead to cardiac arrest. These events unfold within minutes, not decades, as in primary hypertension.

Mentioning this risk is relevant because hypotension is one of the most common side effects of blood pressure drugs across all major classes. Beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics can all drive blood pressure below the level needed to keep key organs adequately supplied.

The risk of hypotension increases with dehydration, low salt intake, missed meals, heat exposure, or combining drugs from different classes. In practice, the effort to lower mildly elevated readings often produces a state that is physiologically more dangerous than the original condition.

But I don't experience any side effects

Antihypertensive drugs are commonly prescribed in low, standardized doses that are quickly compensated for by the body, so there are no measurable side effects.

If blood pressure truly drops in someone whose body relies on higher pressure for adequate oxygenation and nutrient delivery, there should be a perceptible consequence such as fatigue, lightheadedness, or another signal of physiological strain.

When none is felt, it suggests one of two possibilities: the drug dose is too small to have an effect, or the body has compensated by making the heart work harder, masking the drug's influence. Neither outcome represents genuine healing.

Clinical trials frequently cited to justify long-term medication use do not reflect this real-world complexity because participants are carefully selected, closely monitored, and treated under ideal conditions that exclude most of the variables of daily life.

Outside those controlled settings, people mix multiple drugs, live under chronic stress, vary in diet and hydration, and experience a far wider range of reactions than the published data imply.

Let's add all this up…

Antihypertensive drugs for patients with primary or misdiagnosed hypertension create a false sense of security, cause undesirable side effects, place extra wear and tear on the heart, and, as time goes on, require more potent drugs to subdue blood pressure because of self-adaptation.

By themselves, antihypertensive drugs do not prevent cardiovascular disease or stroke because they cannot reverse atherosclerosis, they do not prevent blood clotting, they do not make the heart any healthier, and they do not cap occasional blood pressure spikes related to exercise or high-stress events.

The side effects of antihypertensive drugs are likely to harm or kill a compliant patient faster than primary hypertension, particularly in combination with diuretics and other drugs commonly prescribed to treat the side effects of the original treatment.

However, in case your hypertension isn't primary, not treating it may expose you to the inevitable risks of kidney failure, aneurysm rupture, myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac arrest, or stroke.

What to Do About Your High Blood Pressure?

The primary functional (reversible) factors of consistently high blood pressure are:

-

A diet high in carbohydrates and sweeteners. It keeps blood pressure high because the body turns carbohydrates into glucose. When glucose enters the bloodstream, it stimulates the release of insulin, and the excess glucose is transformed into triglycerides for storage as body fat. In turn, high insulin and triglycerides impact blood pressure for reasons described in the next two points. Supporting evidence:

Patients with high blood pressure, as a group, are insulin resistant, glucose intolerant, hyperinsulinemic, and dyslipidemic, with evidence of endothelial dysfunction. There is substantial evidence supporting the view that insulin resistance and/or compensatory hyperinsulinemia have a role in blood pressure regulation and may predispose a substantial number of individuals to develop high blood pressure.

Insulin Resistance, Hypertension, and Coronary Heart Disease.

The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 5(4), 269 [link]. -

A diet high in animal and/or plant fats. Despite what you may hear from the advocates of carnivore and paleo diets, large amounts of animal and plant fats turn into triglycerides and body fat just like the fat from too much glucose. Supporting evidence:

Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and total peripheral resistance were greater in participants following the consumption of the high-fat meal relative to the low-fat meal. The findings of the present study are consistent with the hypothesis that even a single high-fat meal may be associated with heightened cardiovascular reactivity to stress and offer insight into the pathways through which a high-fat diet may affect cardiovascular function.

A High-Fat Meal Increases Cardiovascular Reactivity to Psychological Stress in Healthy Young Adults. The Journal of Nutrition, 137(4) [link]. -

Consistently high levels of insulin. It keeps high blood pressure up because insulin is a vasoconstricting hormone, meaning it commands blood vessels to tighten up. It takes more pressure to push the blood through the constricted blood vessels. Supporting evidence:

The coexistence of insulin resistance and hypertension can be viewed as a cause-effect relationship (insulin resistance as a cause of hypertension or vice versa) or as a noncausal association. Insulin can increase blood pressure via several mechanisms: increased renal sodium reabsorption, activation of the sympathetic nervous system, alteration of transmembrane ion transport, and hypertrophy of resistance vessels.

The inter-relationship between insulin resistance and hypertension

Drugs. 1993;46 Suppl 2:149-59 [link]. -

Consistently high levels of triglycerides in the blood. Triglycerides refer to highly dispersed fats that circulate in the blood. Dispersed fats make the blood more viscous and heavier. It takes a lot more pressure to push the heavy and viscous blood to all of the organs, from the brain to the toes. Supporting evidence:

In rural residents, elevated TyG [triglyceride and glucose – KM] index trajectories were associated with the risk of hypertension. The TyG index is valuable for assessing insulin resistance among residents with hypertension in remote rural areas.

Association between triglyceride glucose index trajectory and risk of hypertension in rural residents: a prospective cohort study. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 38793 [link]. -

High amount of body fat. The connection with the body fat (adipose tissue) is less obvious and not well known to the public and doctors alike. The reason high body fat increases blood pressure is because the fat in the body is stored in the specialized fat cells called adipocytes or lipocytes.

Fat cells receive a blood supply through an extensive network of blood vessels within adipose tissue. Fat cells stimulate the growth of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) during weight gain when the number and size of fat cells increase.

This process ensures that expanding fat tissue continues to receive sufficient nutrients for its metabolic demands. The larger the network of the blood vessels, the more pressure it takes to push the blood through the adipose tissue to every cell. Supporting evidence:

The prevalence of obesity has tripled over the past five decades. Obesity, especially visceral obesity, is closely related to hypertension, increasing the risk of primary (essential) hypertension by 65%–75%.

Mechanisms and treatment of obesity-related hypertension—Part 1: Mechanisms. Clinical Kidney Journal, 2024; 17(1) [link].

These factors are reversible because you can reduce the amount of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in your diet to the body's actual needs. You can also eliminate all natural and artificial sweeteners.

The effort will reduce the amount of insulin and triglycerides relatively quickly and will gradually provide a measurable reduction in blood pressure.

If you stay with a moderate and balanced diet long enough, you can also lose excess weight and reduce the load on the heart to supply active fat cells with nutrients.

That effort will help to normalize blood pressure in 90% to 95% of the primary hypertension cases.

The remaining 5% to 10% of the organic (irreversible) causes of secondary, isolated systolic, resistant, and malignant hypertensions are the domain of medical doctors and should be addressed by them.

To help you with safe and effective weight loss, I recommend reading these guides:

How to Stop Weight Gain as You Age

How to Maintain a Normal Weight at Any Age

22 Reasons Why Women Gain Weight Faster Than Men

Of course, it would be great if you exercise regularly and reduce stress, but that wouldn't be enough as long as you are affected by metabolic syndrome.

If you didn't hear about something, it doesn't mean it doesn't exist

Although the connection between high body fat and high blood pressure is well established in the medical literature, it is rarely explained to the public in plain language.

Adipose tissue requires its own vascular supply

As fat mass increases, adipocytes stimulate angiogenesis. More fat means more blood vessels, and that expanded

vascular network increases total blood volume and total vascular resistance. Higher volume plus higher resistance

means higher baseline pressure.

Adipose tissue produces hormones that raise blood pressure

Fat cells are endocrine organs. They secrete leptin, resistin, angiotensinogen, TNF-alpha, and other molecules that

increase sympathetic tone, constrict vessels, and alter sodium handling. This biochemical activity pushes blood

pressure upward, independent of weight alone.

Visceral fat interferes with renal pressure regulation

Fat accumulation around the kidneys and within the renal sinus increases intrarenal pressure, alters sodium

excretion, and disrupts the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. That drives chronic elevation of blood pressure.

Increased adipose mass increases cardiac workload

The heart must supply oxygen and nutrients to every gram of metabolically active tissue. The more adipose tissue a

person carries, the more volume and pressure the heart must generate to perfuse it.

If you have ever seen liposuction surgery, it is incredibly bloody, and blood loss is one of its main risks.

Prescription drugs that may cause elevated blood pressure

Several major drug groups are known to raise blood pressure through fluid retention, sympathetic stimulation, vascular effects, or direct interference with blood-pressure-regulating hormones.

The most common culprits include:

— Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which reduce renal blood flow and promote sodium retention;

— Oral contraceptives and hormone therapies that contain estrogen;

— Corticosteroids are used for inflammation and autoimmune disorders;

— Antidepressants, particularly SNRIs and certain tricyclics;

— Common cold and sinus remedies that contain decongestants such as pseudoephedrine;

— Immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and tacrolimus, stimulants prescribed for attention and wakefulness disorders, and some cancer therapies that disrupt vascular function;

— Over-the-counter agents such as caffeine pills, licorice supplements, and high-dose herbal stimulants.

This list is not complete. Whatever prescription or OTC medications you are taking, check the Prescription Information booklet included with the drug or review the official documentation online.

Nutritional deficiencies that increase blood pressure

Paradoxically, the dietary advice commonly given to reduce blood pressure and the digestive side effects of antihypertensive medications contribute to deficiencies of key nutrients that regulate vascular tone, blood volume, oxygen delivery, and metabolic balance. The most important of these nutrients are:

Protein deficiency causes fluid to move out of the bloodstream, prompting the kidneys to retain sodium and water to stabilize circulation. This increases blood volume and raises pressure.

Vitamin C deficiency contributes to hypertension because it reduces the production of nitric oxide, a molecule that helps blood vessels relax and widen. Cases of vitamin C deficiency have shown significant elevation in pulmonary artery pressure and resistance.

Vitamin D deficiency increases renin activity and produces a more constricted vascular system. Clinical and observational studies show that low vitamin D is associated with higher resting blood pressure even after adjusting for other variables.

B-12 and Folate deficiency cause anemia. In turn, anemia increases blood pressure because the heart must pump harder to supply enough oxygen to the body. Indirectly, low B-12 and folate increase homocysteine levels, which stiffen arteries, reduce nitric oxide availability, and raise blood pressure.

-

Magnesium, Calcium, and Chloride. Magnesium deficiency increases vascular constriction. Low calcium raises parathyroid hormone, which tightens vessels. Low chloride interferes with renal sodium handling. These pathways operate independently of weight or glucose metabolism.

Iron deficiency causes anemia by reducing hemoglobin production and impacting oxygen transfer. It also contributes to hypertension by causing abnormal function in the smooth muscle cells of the blood vessels in the lungs, leading to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). This condition increases pressure in the lungs' arteries, strains the heart, and can lead to heart failure.

Iodine deficiency lowers thyroid hormone production. Hypothyroidism slows metabolism, reduces cardiac efficiency, and increases peripheral resistance, which in turn raises blood pressure.

Copper deficiency affects proper collagen cross-linking in arterial walls. In turn, stiffer vessels generate higher systolic readings.

With the exception of protein deficiency, supplementation is the only option for eliminating and preventing these deficiencies because modern diets, age-related absorption decline, medication interactions, and restricted eating patterns rarely provide enough of these nutrients to restore optimal levels on their own.

Keep in mind that low quality supplements can increase blood pressure because they may contain poor quality ingredients, outdated formulations, non-bioavailable forms of B-complex vitamins, contaminants, unstable forms of minerals, hidden stimulants, and allergens that place additional stress on the liver, kidneys, and cardiovascular system. Or they may not help at all.

Takeaways

The following points summarize what matters the most, what is often misunderstood, and what you should keep in mind when evaluating your own blood pressure readings and what to do about them:

Blood pressure rises and falls throughout the day in response to posture, meals, activity, temperature, hydration, and stress. A swing of 10 to 20 points in either direction is normal physiology, not pathology. A single clinic reading taken under artificial conditions cannot represent a person's true baseline.

The system classifies 90% to 95% of all cases as primary hypertension because it cannot identify a specific cause. Once you eliminate bias, white-coat effects, measurement errors, caffeine, hunger, and stress, most of those cases disappear. The remaining 5% to 10% require treatment by the best cardiologist available.

A large part of the hypertension "epidemic" has been artificially manufactured over the past 40 to 50 years to generate long-term revenue for clinics, insurers, and pharmaceutical companies.

Most people diagnosed with hypertension never actually had a chronic disease from the start. The numbers that lead to those diagnoses often come from stressed, rushed, or poorly performed office readings. Without confirming the basal blood pressure at home over several mornings, the diagnosis remains a speculation.

Persistent hypertension is a symptom of evolving cardiovascular disease: narrowed arteries that resist blood flow (atherosclerosis), an enlarging heart working against increasing resistance (cardiomyopathy), fluid buildup related to declining pumping ability (congestive heart failure), and peripheral blood vessels of the brain, leg, and feet already showing structural damage (peripheral vascular disease).

Drug treatment for misdiagnosed hypertension causes more problems than it solves. Antihypertensive medications affect the entire body, not just the blood vessels. Diuretics exacerbate side effects by reducing plasma volume and electrolytes, and lead to additional prescriptions. This cycle results in side effects severe enough to harm careers, safety, and long-term health.

For 90% to 95% of adults with primary hypertension, reducing elevated insulin, high triglycerides, and excess body fat restores normal blood pressure more reliably and with fewer risks than any medication.

Exercise and stress reduction help, but cannot compensate for a metabolic state that keeps pressure high. For the remaining 5 to 10 percent, proper medical evaluation is essential because the underlying causes are structural and non-negotiable.

If your blood pressure is high at home first thing in the morning for several days in a row, you need to identify why. And if you want to fix it, you need to address the metabolic drivers that create chronically tight vessels and heavy blood in the first place.

Do not terminate medication on your own because sudden withdrawal can be dangerous. If your original diagnosis was questionable, deprescribing must be handled by a physician who understands how to taper these drugs safely and monitor the transitions.

Be prepared for pushback from medical professionals. It is easier to blame the messenger than to revisit flawed assumptions, correct earlier diagnoses, or acknowledge that a large share of hypertension cases were wrong.

Blood pressure drugs may reduce your resistance to viral infections by reducing circulation, weakening mucosal defenses, and disrupting sleep, hydration, and electrolyte balance. I covered these mechanisms in How to Prevent Flu and COVID-19 Infections and Complications guide. Anything that weakens circulation and immunity raises the odds of a harder illness, more complications, and a longer recovery.

Please consult these takeaways when reviewing your own blood pressure numbers and deciding what deserves the most attention, especially if you want to avoid the risks of a wrong diagnosis and unnecessary treatment. No reasonable physician will dismiss your concerns when you present them in a calm, respectful, and straightforward way.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. How can I tell whether my high blood pressure reading at the doctor's office was real or just a stress response?+

Basal blood pressure is measured right after you wake up, without leaving the bed, and before food, caffeine, talking, or any activity. If your basal numbers over several days are far lower than the office reading, it means the clinic result was a stress response rather than primary hypertension. If your basal numbers are close to the clinic numbers, then the elevation is real, and you need to identify what is driving it.

Q. What is the correct way to measure basal blood pressure at home, and how many days of readings do I need?+

Basal blood pressure is best measured immediately after waking, before getting out of bed, but in a slightly elevated, supported position. Raise your upper body with a pillow or the headrest so you are close to a relaxed semi-reclined posture. Keep your back supported, legs straight, and the arm with the cuff resting at heart level.

Take the reading before speaking, checking your phone, drinking water, or sitting upright. This captures your true baseline without the distortions of movement, stress, or gravity shifts. You need three to five consecutive mornings under identical conditions to establish a reliable pattern.

Q. What specific dietary changes lower blood pressure the fastest without medication?+

The fastest way to bring blood pressure down without medication is to remove the metabolic triggers that keep insulin and triglycerides elevated. That starts with eliminating all sweetness, including artificial sweeteners, because anything sweet drives insulin up and constricts blood vessels.

Reducing carbohydrates to under 150 grams per day lowers glucose levels and cuts the insulin load even further.

Eliminating vegetable oils and keeping total dietary fat under 100 grams per day reduces triglyceride production.

Keeping protein under 100 grams per day prevents excess amino acids from being converted into glucose and stored as body fat.

When you stay within these limits, blood vessels dilate, blood becomes less viscous, and the heart no longer has to push blood as hard.

You will see lower readings after several weeks because the body needs time to eliminate the conditioned reflexes that drive insulin secretion regardless of food intake.

If you are already taking medication while making these changes, you have to be careful because the medication can drive your blood pressure too low. To taper it safely, tell your doctor what you are doing and ask them to reduce the prescription gradually until you no longer need it.

Q. How do carbohydrates, fats, and proteins raise blood pressure differently, and which one matters most?+

Carbohydrates raise glucose and produce the strongest insulin response. Insulin constricts blood vessels, so pressure goes up almost immediately. Excess carbohydrates also turn into triglycerides, which make the blood heavier and harder to push through narrow vessels.

Dietary fats raise triglycerides in the blood. Just like with carbs, the heart has to generate more force to move viscous blood it through the vascular system. This effect is even more pronounced in people with obesity because adipose tissue depends on an expanded network of tiny blood vessels.

Protein affects blood pressure more slowly. When you eat more protein than your body needs, the excess is converted into glucose and then into triglycerides. It feeds the same cycle as carbohydrates and fat, but with a delay.

Q. Is it safe to reduce or eliminate blood pressure medications once my readings normalize?+

It's not just safe, but critical because staying on medication after your blood pressure has normalized can push it too low. After insulin drops, triglycerides fall, and blood becomes easier to circulate, the same drug dose that once had little effect may become overpowering and cause dizziness, fatigue, fainting, and cognitive problems.

Do not stop the medication abruptly. The right approach is to explain to your doctor that your basal blood pressure numbers have normalized and ask for a gradual reduction.

Q. How do I know if my elevated blood pressure is a sign of developing heart disease rather than the cause of it?+

If basal blood pressure is consistently high, it reflects cardiovascular changes rather than a temporary response.

Q. What is the real risk of leaving mild, primary hypertension untreated if my basal readings are normal?+

If your basal readings are normal, the risk of leaving so-called primary hypertension untreated is minimal. Basal pressure reflects the true state of your cardiovascular system. If it is consistently normal, the elevated daytime numbers are driven by stress, posture, activity, temperature, or stimulants, not by underlying disease.

Treating this pattern with medication creates more risk than benefit because the drugs suppress a number that was never abnormal in the first place. The actual danger lies in misdiagnosis, unnecessary drug exposure, and the side effects that follow. The goal is to treat real hypertension, not the temporary fluctuations that appear during the day.

Q. What proof do you have that you are correct, and all of the experts are wrong?+

I am not claiming that all experts are wrong. I am pointing out that the underlying information behind my thesis is already published in clinical guidelines, physiology texts, drug monographs, and large observational studies.

Everything I describe can be verified by checking how blood pressure is supposed to be measured, how antihypertensive drugs work, and what their documented side effects are. The same applies to the role of insulin, triglycerides, and body fat in regulating vascular tone.

When you compare these primary sources with the way hypertension is diagnosed and treated in routine practice, the gaps become obvious. My work simply connects those points in plain language and shows how they apply in everyday situations.

This guide is focused on healthy adults who are misdiagnosed with a manufactured diagnosis of primary hypertension. It has nothing to do with secondary hypertension or the small group of people who present with consistently high blood pressure numbers driven by kidney disease, hormonal disorders, or vascular problems. In those cases, medication may help a narrow subset of patients, as the data in Myth #3 suggests.

Author's Note

When I started my journey with functional nutrition in the late nineties, I was a total basket case health-wise, and hypertension was the least of my concerns.

In the process of recovering from late-stage type 2 diabetes, I normalized my weight, blood sugar, triglycerides, and insulin, and most of the other hypertension triggers went away.

Since then, I have never returned to the diet, habits, and lifestyle that made me sick in the first place, and as I got older and more sensitive to alcohol, coffee, and occasional overeating, I eliminated them as well.

I also started paying more attention to sleep, stress, and relationships by improving the good ones and cutting out the toxic ones, while cultivating the habits already recommended throughout this and other guides.

The table below lists the top 22 conditions that affect my contemporaries. Neither my wife nor I has any of them. Not even one.

I am a public person, so lying about it isn't an option. Like everyone our age (71 and 70 at the time of writing), we have Medicare, and all of it can be verified if ever challenged. The last thing I would do is risk compromising my integrity over an article about hypertension.

Top 22 Health Conditions Affecting People Ages 65 to 75

| Condition | Prevalence (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension (65–74) | 71.8–73.7% | CDC |

| Polypharmacy (taking multiple drugs) | 37–65% | JAMA |

| Atherosclerosis (60–79) | 37–50% | AHA |

| Insomnia symptoms (older adults) | 30–48% | AASM |

| Tinnitus (ringing in the ears) | 24–45% | Frontiers Neurology |

| Chronic fatigue | ~42.6% | Nature |

| Urinary incontinence (women 65–80) | ~51% | University of Michigan |

| Arthritis (≥75; lower for ages 65–74) | ~53.9% | CDC |

| Chronic pain (older adults) | 36% | CDC |

| Hearing loss (any, 64–75) | ~33% | Hearing Health Foundation |

| Chronic constipation, occasional (60+) | ~33% | AAFP |

| Osteoporosis (women 65+) | 27% | CDC |

| Falls or fall injuries (65+) | ~25% | NCOA |

| Type 2 diabetes (65–74) | ~20–25% | CDC |

| Any cancer diagnosis (65–74) | ~20% | American Cancer Society |

| GERD (older adults) | 14–20% | Frontiers Medicine |

| Insomnia disorder (older adults) | 12–20% | AAFP |

| Memory loss (subjective, 65+) | 11.7% | CDC |

| Fecal incontinence (NHANES) | 8.39% | NHANES |

| IBS (older adults) | 4–10% | Nature Reviews Gastro. |

| Alzheimer's dementia (65–74) | ~5% | Alzheimer's Association |

| Blindness or severe vision loss (65+) | 3–4% | NEI |

How many people do you know in their early forties, fifties, sixties, or seventies who don't have a single chronic condition from that list and don't take a single medication? I personally don't know of any, and I know a lot of people.

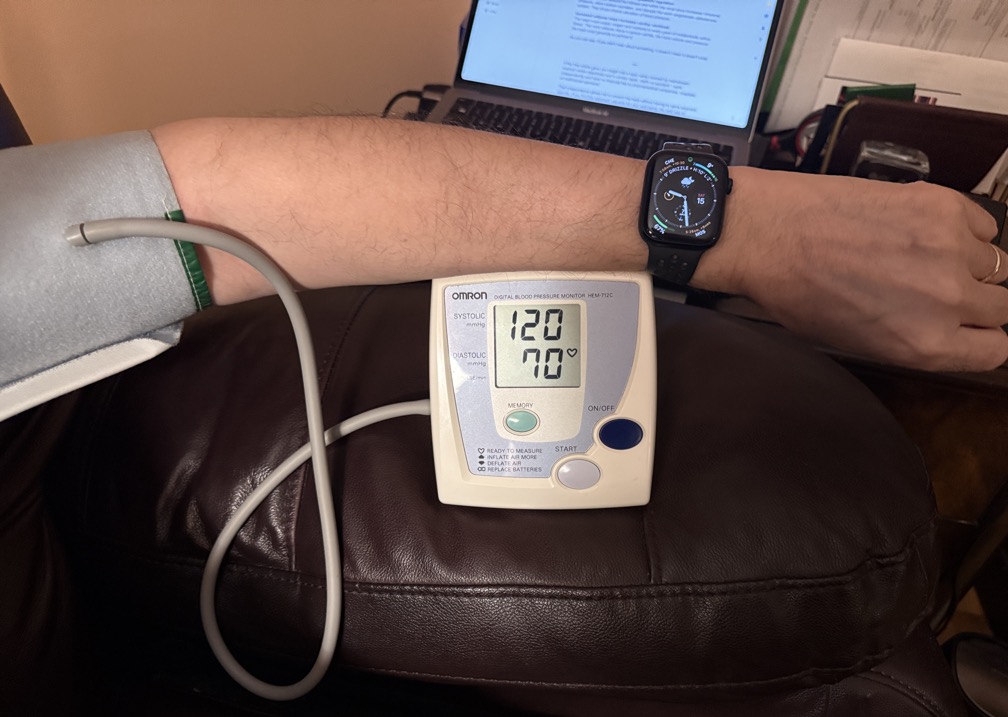

For full transparency, here is my most recent blood pressure reading. I measured it at 9:28 p.m. on November 15, 2025, right before writing this section, and my wife took the photo with my iPhone. My pulse was 69.

I have been up and working since 7 a.m. to complete this guide. To save my back, I write in a recliner with a MacBook on my lap. This photo is directly from the iPhone, unmodified in any way.

Out of curiosity, a few minutes later, I ran up and down four flights of stairs from the second floor to the basement and back, and my immediate reading in the same chair was 127 over 68, pulse 86.

My basal blood pressure when I wake up is around 100–110 over 60–65, and pulse under 60. I do practice what I preach!

Also, check out my arm in the photo — no gray hair, no skin discoloration or thinning, no prominent veins, and no age spots. You rarely see that in a 71-year-old man. If you start early enough, you too can achieve a similar result.

You can learn more about why and how I've managed to pull this off in the Why Should You Trust Me? essay.

***

If this free article gave you insight into a topic rarely covered by mainstream medical media objectively and in similar depth, that's no accident. I work independently and have no financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, or institutional sponsors.

That independence allows me to present the facts without having to serve anyone's agenda. If you find this approach valuable for your well-being, the best way to support my work is by sharing this article with others.

Every repost, forward, or mention helps amplify the reach and makes future work like this possible. Thank you for taking the time to read and for supporting my work!