44 Serious Disorders Caused by Salt Deficiency

The long-standing recommendation to restrict salt intake for people with high blood pressure, heart disease, or diabetes has been mainstreamed for two generations. But no one was told that reducing salt damages the stomach, colon, kidneys, heart, brain, muscles, bones, joints, and mental health faster than alcohol damages the liver or smoking destroys the lungs.

This publication identifies 44 entirely avoidable but otherwise life-altering serious disorders caused directly by a low-salt diet and/or deficiency. And they’re just the tip of the iceberg, considering the cascade of treatments, medications, and side effects that follow.

The most maddening thing about it is that numerous researchers with strong academic credentials have rebutted the link between dietary salt and hypertension, and their findings have been published in leading peer-reviewed medical journals for quite some time.

Adding insult to injury, the effect of low-salt diets on high blood pressure was less than a 1% reduction after evaluating 23 clinical trials (#3 below). In practical terms, it means that if your blood pressure was 160/90, on a low-salt diet, it has changed to 158/89, a totally irrelevant difference.

And that's even before mentioning that "BP measurement is often suboptimally performed in clinical practice, which can lead to errors that inappropriately alter management decisions in 20% to 45% of cases."

Wrap your head around it — up to 45% of patients may be diagnosed with hypertension and prescribed medication simply because their blood pressure wasn't measured properly. And this quote didn't come from a fringe conspiracy lunatic, but from the venerable American Medical Association in the article titled 4 big ways BP measurement goes wrong, and how to tackle them.

The Truth Is There for Anyone Who Wants to Know

Here are five examples of academic publications that refute the effectiveness of low-salt diets and highlight their possible harms. I added my commentaries and "translations" into plain English from academic jargon where necessary:

-

Alderman MH. "Dietary sodium and cardiovascular disease: the 'J'-shaped relation." Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(5):903-907. JAMA Network

"Skeptics argue that modification of this single surrogate end point does not guarantee a health benefit as measured by morbidity or mortality [Improving blood pressure has no effect on health outcomes — KM]. Instead, they note that salt restriction capable of reducing blood pressure also unfavorably affects other cardiovascular disease surrogates. [Salt restriction may improve blood pressure but worsen lipid profiles, insulin resistance, or hormone balance, and doesn't reduce mortality — KM].

In medical research and clinical trials, the term "surrogate endpoint" is a substitute measure used to see how well a treatment works. In this particular case, a surrogate endpoint meant that researchers used blood pressure readings to predict the risk of heart disease, rather than waiting to see if someone actually develops it (morbidity) or dies from it (mortality).

Dr. Michael H. Alderman is a Professor Emeritus of Medicine and Population Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and a former President of the American Society of Hypertension. He is known for challenging the blanket salt-restriction guidelines, emphasizing that low sodium intake may have unintended harms.

-

McCarron DA. "Normal range of human dietary sodium intake: a perspective based on 24-hour urinary sodium excretion worldwide." American Journal of Hypertension. 2013;26(10):1218-1223. [Link]

"The recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Sodium Intake in Populations—Assessment of Evidence found “no evidence for benefit and some evidence suggesting risk of adverse health outcomes associated with sodium intake levels in ranges approximating 1,500–2,300mg per day,” a range well below the lower limit of normal that our data defines"

Dr. David A. McCarron is a Former professor of medicine at UC Davis. He has argued that mineral balance (e.g., potassium, calcium, magnesium) and overall diet quality matter more than sodium alone in determining cardiovascular risk. Co-authored opinion pieces and studies critical of low-salt guidelines.

-

Graudal N, Jürgens G, Baslund B, Alderman MH. "Compared with usual sodium intake, low- and excessive-sodium diets are associated with increased mortality: a meta-analysis." American Journal of Hypertension. 2014;27(9):1129-1137. PubMed

This particular study, a meta-analysis of 23 clinical trials and, by all counts, an elephant in the room, found that low-salt diets reduced blood pressure by less than 1%, a negligible change. It also reported that in patients with metabolic syndrome (prediabetes, diabetes, or obesity), salt restriction could paradoxically raise blood pressure. In other words, the entire campaign to reduce salt intake as a strategy to prevent hypertension was based on a deeply flawed premise.

For context, the authors defined "excessive" salt intake as approximately 12.4 grams per day, or nearly 2.5 times the U.S. recommended daily allowance. I'm not suggesting you consume this much either.

Dr. Niels Graudal is a Clinical Professor, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark. He is the lead author of major meta-analyses showing that both low and high sodium intakes are associated with increased mortality risk along the U-shaped curve.

-

Mente A, O'Donnell M, Rangarajan S, et al. "Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from four studies." The Lancet. 2016;388(10043):465-475. The Aga Khan University

"Compared with moderate sodium intake, high sodium intake is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and death in hypertensive populations (no association in normotensive population), while the association of low sodium intake with increased risk of cardiovascular events and death is observed in those with or without hypertension." [If you already have high blood pressure, too much salt is bad for you. If you don't have high blood pressure, a low-salt diet increases your risk of death — KM.]

Dr. Andrew Mente is an Epidemiologist at the Population Health Research Institute, McMaster University, Canada. He is the co-author of the large international PURE study, which found no increased cardiovascular risk at moderate salt intake levels.

-

Dr. James DiNicolantonio. The Salt Fix: Why the Experts Got It All Wrong—and How Eating More Might Save Your Life, August 4, 2020. Amazon.com

"For more than forty years, our doctors, the government, and the nation’s leading health associations have told us that consuming salt increases blood pressure and thus causes chronic high blood pressure. Here’s the truth: there was never any sound scientific evidence to support this idea. Even back in 1977, when the government’s Dietary Goals for the United States recommended that Americans restrict their salt intake, a report from the U.S. Surgeon General admitted there was no evidence that a low-salt diet would prevent the increases in blood pressure that often occur with advancing age." p. 7

James J. DiNicolantonio is a cardiovascular research scientist and doctor of pharmacy at Saint Luke's Mid-America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Missouri. He serves as the Associate Editor of Nutrition and the British Medical Journal's (BMJ) Open Heart, a journal published in partnership with the British Cardiovascular Society.

These experts differ in methodology and tone, but they all share a willingness to challenge the entrenched anti-salt orthodoxy with physiological facts, epidemiological data, and clinical insights.

Why Bother?

I've chosen to revisit this topic because, aside from Dr. DiNicolantonio, most of their work has focused on hypertension and kidney function and was limited to academic press, and none have my depth of experience with functional gastrointestinal disorders, a critical area that remains overlooked in the salt debate.

My goal in this article is to help you understand the true role of salt in gut health and digestion so that you can protect one of the most critical parts of your body from preventable harm.

Also, I'm not suggesting that you binge on salt. Like anything else, excessive salt is harmful, and above a certain amount, outright toxic. For a 70 kg person, the lethal range is approximately 14 to 35 grams of salt taken at once, depending on age, kidney function, hydration status, and rate of absorption. Death typically results from hypernatremia, which causes brain shrinkage, seizures, coma, and ultimately respiratory failure or cardiac arrest. But that doesn't mean too little salt, or none at all, is somehow "healthy."

Any extreme is equally deadly. Drinking six or more liters (1.5 gallons) of water within a few hours, for example, has been documented to cause death from dilutional hyponatremia, especially when water isn't accompanied by salt or the person is already salt-depleted.

The terms hyponatremia and hypochloremia refer to acute deficiencies of sodium and chloride, respectively. The term -natremia is derived from the Latin name for sodium. Functionally, both terms describe the same condition — an acute deficiency of sodium chloride (NaCl) in the body because table salt is the primary source of both sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl) in the human diet. Hyper-anything refers to the opposite end of the spectrum.

A Note of Caution to Vegans and Vegetarians

Both sodium and chloride are essential electrolytes, but in plant-based foods, they are present only in trace amounts. Even so-called “high-sodium” vegetables like spinach, celery, kale, lettuce, or cabbage contain too little sodium to meet your physiological needs. I put “high-sodium” in quotes because its actual amount is modest, typically around 20 to 40 mg per serving, too small to move the needle.

And to get even that meager amount, you need to eat these vegetables raw, because boiling depletes much of the mineral content in plants. The same goes for chloride, which is also water-soluble and lost during cooking, further reducing your intake of this critical electrolyte.

For most people, the overwhelming source of both sodium and chloride in the diet is table salt. Without it, meeting the body's daily requirement for these two essential electrolytes on a plant-based diet is virtually impossible.

If Being Right Is Crazy, So Be it!

Now, let's address my claims that "reducing salt consumption damages stomachs, colons, kidneys, hearts, brains, muscles, bones, joints, and mental health faster than alcohol damages the liver or smoking damages the lungs?"

Reading this, some people may say, "How dare you make these crazy claims?"

I hear you! Let me explain, organ by organ, what happens when the body doesn't get enough salt from your diet. I’ve added numbers in parentheses (1, 2, 3...) next to each related disorder to show how many total complications can arise from what, at first glance, may seem like a trivial issue.

Some of the explanations you'll read below are relatively technical. It isn't because I want to impress you with my knowledge, but because this text will be read and ruthlessly scrutinized by skeptics, critics, naysayers, lawyers, and medical professionals. If I simplify it too much, it will be dismissed as inconsequential, and rightfully so.

To assure you that I don't have an ax to grind or, somehow, am crazy, I used ChatGPT to verify whether all of my claims are accurate and supported with mainstream medical references.

If you’re thinking that ChatGPT might be hallucinating or just telling me what I want to hear, it’s not. The latest versions of this tool actively search and verify information against real academic sources online, much like Google used to, only faster, with more context, and without favoring big advertisers who push their own agendas on top of the searches.

Tap the "Is it true?" link at the end of each paragraph to read ChatGPT's reply and review the sources:

-

Stomach. Salt deficiency contributes to the development of (1) heartburn, (2) GERD, (3) gastritis, (4) peptic ulcers, and (5) stomach cancer by impairing gastric acid production. Chloride from salt is needed to produce hydrochloric acid. Without enough of it over time, acid levels fall, protein digestion breaks down, and fermentation, inflammation, and mucosal damage set in. This dysfunction can progress to ulcers, gastric atrophy, and eventually carcinogenic changes in the stomach lining. Is it true?

-

Colon. Salt deficiency is a key contributor to (6) irritable bowel disease, (7) diverticular disease, and (8) colon cancer because it leads to (9) chronic constipation. When there isn't enough salt in the diet, the body pulls every last bit of salt and water out of the stool to keep the blood circulating. That's what makes the stool hard, dry, and painful to pass. Over time, this constant straining stretches and injures the colon, causes inflammatory bowel disease (10), and sets the stage for serious damage—everything from diverticulosis to cancer. Is it true?

-

Heart. Salt deficiency is one of the factors behind (11) heart disease because sodium is essential for maintaining normal blood volume. In its absence, blood volume contracts, forcing the heart to beat faster and harder to maintain the delivery of fluids, nutrients, and oxygen to all organs. This overcompensation increases cardiac workload and accelerates structural deterioration, especially in the context of aging or preexisting weakness. Is it true?

-

Kidneys. There's a strong physiological link between salt deficiency and kidney disease because insufficient sodium reduces renal perfusion and filtration pressure. This impairs the kidneys' ability to regulate fluids and eliminate waste. In response, the body activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), increasing (12) systemic (irreversible, not depended on external stressors) blood pressure and promoting fibrosis, a pathway that contributes to (13) chronic kidney damage over time. Is it true?

-

Brain. Salt deficiency contributes to neurological decline, including (14) dementia, (15) Alzheimer's, and (16) Parkinson's, because chloride ions are critical for neuronal signaling and brain volume regulation. Chronic hyponatremia, even when mild, disrupts synaptic transmission, weakens the blood-brain barrier, and impairs mitochondrial function in neural tissue, all of which are implicated in neurodegenerative processes. Is it true?

-

Bones and joints. Salt deficiency indirectly undermines bones and joints because it causes chronic protein malnutrition and mineral loss. When stomach acid is too low to digest dietary protein, amino acid absorption drops. This undermines (15) muscle mass (sarcopenia), collagen synthesis, and calcium uptake—key factors in the development of (16) osteoporosis and (17) degenerative joint disease. Is it true?

-

Mental health. Salt deficiency, and particularly hyponatremia (low sodium), is well-documented to cause cognitive and mood disturbances because sodium and chloride are essential for neurotransmission, hormonal regulation, and energy metabolism. When salt levels drop, so do adrenal function and blood pressure, leading to (18) chronic fatigue, (19) brain fog, (20) anxiety, and (21) depressive states. Is it true?

Even after twenty-five years of debunking the nastiness of the 'low-salt is good for you' propaganda, I still find these results shocking—and they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

Let's Go Under the Water to See the Rest of the Iceberg

I intentionally led with the most controversial conditions first to get your attention. Here's the list of other well-documented and widely recognized complications and side effects caused by low-salt diets and salt restrictions:

-

High blood pressure. A meta-analysis of clinical trials found that low-salt diets reduced blood pressure by less than 1% (from 140/80 to about 137/80, for example). It also noted that in patients with metabolic syndrome (prediabetes, diabetes, or obesity), salt restriction could paradoxically raise blood pressure. Compared with usual sodium intake, low- and excessive-sodium diets are associated with increased mortality: a meta-analysis, PubMed

-

Diabetes and prediabetes. Salt restriction tends to raise levels of insulin and worsen insulin sensitivity. In one study, putting hypertensive patients on a modestly low-salt diet led to a 40% increase in (22) fasting insulin C-peptide and caused a small rise in blood glucose along with a drop in HDL (good) cholesterol. Sodium restriction and insulin resistance: A review of 23 clinical trials, Journal of Insulin Resistance

I already cited this meta-review by Dr. Niels Graudal at the beginning of this article. It was one of the most shocking findings in his paper. And yet, the cart is still stuck where it was.

-

Dehydration. Sodium is essential for maintaining water balance. A deficiency can lead to (23) dehydration, impairing the body's ability to regulate temperature and function properly. Mayo Clinic - Hyponatremia Overview, National Kidney Foundation

-

Heat Stroke. Salt deficiency can impair the body's ability to sweat and cool down, increasing the risk of (24) heat-related illnesses. National Athletic Trainers' Association - Exertional Heat Illnesses, NATA

-

Hypotension and Risk of Falls. Low sodium levels can cause (25) low blood pressure, leading to dizziness and an increased risk of falls, especially in the elderly. Open Access Government - Maintaining Sodium Levels in a Heatwave, Open Access Government

-

Orthostatic Hypotension. Insufficient salt intake can lead to a drop in blood pressure upon standing, causing (26) dizziness or fainting. ScienceDirect - Sodium Intake in Orthostatic Disorders, ScienceDirect

-

Syncope (fainting). Salt deficiency can contribute to (27) fainting episodes due to its role in maintaining blood pressure and volume. American Heart Association - Neurocardiogenic Syncope, AHA Journals

-

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS). Low salt intake can exacerbate (28) POTS symptoms, including rapid heartbeat and dizziness upon standing. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine - Managing POTS, AHA Journals

-

Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia. Excessive fluid intake without adequate sodium during prolonged exercise can dilute blood sodium levels, leading to (29) hyponatremia. NCBI Bookshelf - Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, NCBI

-

Adrenal Insufficiency (30). Conditions like Addison's disease impair the body's ability to retain salt, leading to salt cravings and deficiency. Mayo Clinic - Salt Craving and Addison's Disease, Mayo Clinic

-

Salt-Wasting Syndromes (31). Genetic disorders such as Bartter and Gitelman syndromes cause excessive salt loss, leading to various health issues. Mayo Clinic - Salt Craving and Addison's Disease, Mayo Clinic

-

Keto-Adaptation Symptoms (32), "Keto Flu." Low-carb diets increase salt excretion, and inadequate replacement can cause fatigue, dizziness, and other symptoms. Virta Health - Sodium and Nutritional Ketosis, Virta Health

-

Delirium and Confusion in the Elderly. Hyponatremia is a common cause of (33) confusion and delirium in older adults. Mayo Clinic - Delirium Overview, Cleveland Clinic

-

Seizure Threshold Reduction. Severe hyponatremia can lower the seizure threshold, increasing the (34) risk of seizures. Mayo Clinic - Hyponatremia Overview, Mayo Clinic

-

Muscle Cramps and Weakness. Salt is crucial for muscle function; deficiency can lead to (35) muscle cramps and weakness. Medical News Today - Muscle Weakness Causes, Medical News Today

-

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, CFS/ME. Salt imbalance may play a role in the fatigue and other symptoms experienced in (36) CFS/ME. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis refers to muscle pain and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. eLife - Muscle Weakness in Chronic Sepsis, eLife

-

Sarcopenia Acceleration. Low salt levels can contribute to (37) muscle wasting and weakness in older adults. WebMD - Sarcopenia Overview, WebMD

-

Dry Skin and Eczema. Salt plays a role in skin hydration; deficiency may exacerbate conditions like (38) eczema. Better Health Channel - Eczema Overview, Better Health Channel

-

Reduced Tear and Saliva Production. Salt is essential for fluid secretion; deficiency can lead to (39) dry eyes and (40) dry mouth. Mayo Clinic - Dry Mouth, Mayo Clinic

-

Impaired Thermoregulation (42). Salt is vital for sweat production; deficiency can hinder the body's ability to regulate temperature. Physiopedia - Physiology of Sweat, Physiopedia

-

Increased Susceptibility to GI Infections (43). Low stomach acid due to salt deficiency can reduce the stomach's ability to kill harmful pathogens. NCBI - Hyponatremia in Infectious Diseases, PMC

-

Urinary Tract Infections and Kidney Infections. Salt imbalance can affect urinary tract function, increasing the risk of (44) genitourinary infections. National Kidney Foundation - Urinary Tract Infections, National Kidney Foundation

I Still Have Doubts! Show Me Real Proof…

Sure. Japan has some of the highest salt intakes in the world, often exceeding 10 grams per day, and yet far lower rates of heart disease, obesity, dementia, and digestive disorders than the United States. Life expectancy in Japan is the highest in the world at 85 years. In the U.S., it's dropped to around 77.

That's an eight-year gap, despite the fact that most older men in Japan still smoke like there's no tomorrow and, by Western standards, many middle-aged working men are functional alcoholics. And don't write this off as Japanese genetics—the rates of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in Japanese Americans begin to resemble U.S. averages within one or two generations.

If Japan's example isn't enough for you, wrap your head around another salt-related paradox. When a victim of a heart attack or stroke is transported to the hospital, they're immediately hooked up to an intravenous drip (IV) with 0.9% Sodium Chloride (NaCl) solution. It has the same concentration of salt as in the blood.

To non-doctors, using salt while treating a heart attack or stroke doesn't make sense, considering mainstream medical advice to protect yourself from both conditions by avoiding salt.

But it's a different story for the doctors because their highest priority is to keep the heart, brain, and all other organs perfused (supplied with fluids and essential electrolytes). Without it, blood pressure can crash, the kidneys can shut down, and the patient can quickly deteriorate (move toward a critical state).

So while most medical professionals preach to avoid salt in theory, in practice, they reach for it the moment the situation gets serious.

And, incidentally, a lot of it — a 1-liter bag of IV solution (like the one above) contains 9 grams of salt, or 55% more than the 5.8 grams recommended daily ((9.0 - 5.8) / 5.8 = 0.55) And all of that salt goes into the patient's body in just 1 to 2 hours, not over 24.

A Little White Lie on Behalf of the Big 'White Death'

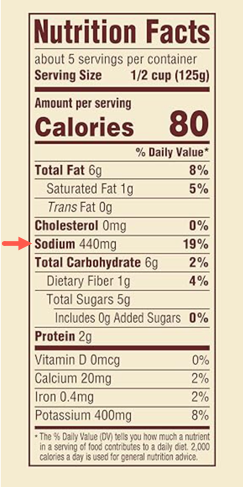

The U.S. Daily Recommended Allowance (DRA) for salt is currently set at 2,300 mg (2.3 g) of sodium per day for healthy adults.

When most people read this recommendation, they naturally assume it means limiting salt intake to 2.3 grams per day. In reality, 2.3 grams of sodium equals 5.8 grams of table salt, or just slightly over one teaspoon.

Here's what's going on:

Salt's chemical formula is NaCl, a combination of sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Sodium makes up about 39% of salt's weight; the other 61% is chloride. So:

5.8 grams of salt × 39% = 2.3 grams of sodium

This deliberate misrepresentation is rooted in U.S. food labeling laws and public health policy. On one hand, it allows manufacturers to underreport the actual salt content of packaged foods by listing "sodium" instead of "salt."

You can see an example in the Nutrition Facts label on the left: the 440 mg of "sodium" listed here actually represents 1,128 mg (1.1 g) of table salt, or 61% more than what you think it is.

On the other hand, this trick encourages consumers to underconsume salt in order to comply with public health recommendations aimed at reducing salt intake, regardless of individual need or context.

So, if you are watching your salt intake either way — not enough or too much — don't get fooled by this 'sleight of hand' because an even bigger victim here was the 'baby' that got thrown out with the bathwater.

By the baby, I meant the less famous second part of the sodium chloride. Low-salt diets reduce chloride (Cl) intake just as much as sodium (Na), even though it's chloride, not sodium, that plays the more critical role in salt deficiency dysfunctions that affect digestion, breathing, brain function, and kidneys. From a strictly physiological standpoint, chloride is critical for:

-

Hydrochloric acid production. I've already discussed this point more than once, but it's worth repeating: Without enough chloride, most of which comes from salt, your body can't generate adequate stomach acid. Low acidity in the stomach impairs the digestion of protein, blocks the absorption of key nutrients like iron, calcium, and vitamin B12, and increases the risk of reflux, bloating, and foodborne infections. So if you struggle with heartburn or indigestion, adding a little bit of salt to your diet may help restore proper stomach acid levels and fix your digestion.

-

Carbon dioxide removal. Chloride helps red blood cells carry carbon dioxide out of the body. It swaps places with bicarbonate to keep your blood's pH in balance and prevent it from becoming too acidic or too alkaline. This process is essential for breathing and staying alive. So if you struggle with sleep apnea or asthma, adding a bit of salt to your diet may help ease both conditions.

-

Regulation of brain activity. Chloride helps regulate brain activity by allowing calming signals to pass through nerve cells. It works through messengers like GABA and glycine, which depend on chloride to slow things down and keep neurons from firing too much. So if you or your teenager struggles with ADHD, adding a bit more salt to the diet might calm the brain more effectively than a prescription for Ritalin, without the side effects.

-

Electrolyte balance and osmoregulation. Chloride helps your kidneys maintain the right balance of salt, potassium, and water in your body. This balance is essential for staying hydrated, keeping your blood pressure stable, and making sure your cells function properly. So if you're dealing with low energy, dizziness when standing up, leg cramps, or taking diuretics, adding a bit of salt to your diet may help ease some of these issues.

As you can see, reducing salt deprives the body of chloride, an essential electrolyte with far-reaching roles in digestion, respiration, brain function, and fluid balance. From producing stomach acid and regulating breathing chemistry to calming the nervous system and supporting kidney function, chloride is central to basic physiological stability. When salt intake drops, all of these systems can become destabilized.

With that in mind, let's turn to practical recommendations for how to consume salt and support your health safely.

How the Salt Is Stored and Lost from the Body

When salt (NaCl) is dissolved in water, it separates into ions of sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻). Accordingly, when the body needs to remove excess salt, it doesn’t flush out table salt per se, but excretes sodium and chloride ions separately.

This distinction matters because the body regulates sodium and chloride independently, and losing too much of either can disrupt blood volume, acid-base balance, and nerve function—even if you're technically “just losing salt.”

So when I talk about “salt loss in urine or sweat,” what’s really leaving the body are salt ions, not actual table salt. When sweat dries on your skin, the white residue you see is sodium and chloride ions that have recrystallized into salt.

Throughout this text, I use the words salt and sodium interchangeably. Technically, this isn’t correct for academic publications written for scientists, but it’s perfectly appropriate here to avoid confusion.

You'll also hear the term “turnover.” It refers to the continuous cycle of fluids entering the body, moving through tissues and systems, and then being lost through sweat, urine, and breathing. It’s not just about how much water the body stores, but how quickly it moves through the system and how often it needs to be replaced along with the electrolytes, like sodium and chloride, that go with it.

Watching for Salt Deficiency Is Just as Important as Watching for its Excess

The actual requirement for maintaining blood volume, acid production, enzyme activation, and cellular function varies widely depending on factors such as age, gender, weight, race, occupation, physical activity, elevation, climate, diet composition, medication, and overall health. So, giving all people the same baseline of 5.8 grams is just as dumb as giving every newborn the same name.

The right approach to determining optimal salt intake is based on compensating for your daily losses. These losses come in two forms:

-

Obligatory losses occur through the body's normal functioning and are not under your conscious control. These include salt lost through sweat, tears, breast milk, urine, stool, and breathing. The volume of these losses depends on a wide range of factors such as ambient temperature, humidity, hydration level, hormonal state, and physical activity. They may vary substantially between workdays and weekends, vacation and daily routine, hot and cold climates, or between sleep and wake hours.

-

Induced losses are caused by your lifestyle and dietary choices. They include low-salt or salt-free diets, endurance exercise, sauna use, diuretic medications, blood donation, alcohol, caffeine, and high fluid intake without salt replacement. Even healthy habits like regular cardio training or eating a plant-based diet can significantly increase salt loss or reduce salt availability if not properly balanced.

Let's review both in greater detail:

Obligatory losses of salt

Salt losses shift constantly based on your age, gender, surroundings, activity level, and health status. The body loses both through urine, stool, sweat, breath, and skin, and these losses can rise dramatically in heat, during exercise, illness, or after time in a sauna. The table below outlines typical daily losses under common conditions. These values are averages, but they make it clear that your salt and hydration needs can easily double or triple without you noticing, especially if you're physically active, live in a warm climate, or are recovering from illness.

|

Condition |

Salt Loss (NaCl) |

Water Loss |

Notes |

|

Basal (rest, mild climate) |

3–4 grams |

1.5–2.5 liters |

Standard urine, minor sweat, normal breathing |

|

Dry indoor air (heated / cooled) |

4–5 grams |

2.0–3.0 liters |

Increased respiratory and insensible loss due to low humidity |

|

Hot weather / Beach day |

6–9 grams |

3.0–4.5 liters |

Continuous sweating and fluid evaporation |

|

Moderate physical work |

8–12 grams |

4.0–6.0 liters |

Repetitive or sustained muscular activity, outdoor labor |

|

High-intensity sport (1–2 hrs) |

10–14 grams |

3.5–5.0 liters |

Includes heavy sweating from team sports or intense training |

|

Fever (moderate) |

6–8 grams |

2.5–4.0 liters |

Elevated temperature increases fluid loss through the skin and lungs |

|

Sauna (20–40 minutes) |

6–10 grams |

1.0–2.5 liters |

Rapid sweating and salt loss; varies by duration, temperature, and body size |

|

Severe fluid loss (vomiting, diarrhea) |

10–20+ grams |

3.0–7.0+ liters |

Water and salt loss depend on severity and duration. |

The amount of salt lost each day varies widely depending on the environment, physical activity, health status, and body size. While the basal losses in a temperate climate are relatively modest, even a brief exposure to heat, exercise, fever, or illness can double or triple both salt and water losses. In such cases, failure to adequately replace both can lead to dehydration, fatigue, digestive issues, and circulatory stress.

Gender and ethnicity can influence salt loss, primarily due to differences in sweat rate, sweat composition, body size, and hormonal regulation, though the variations are generally moderate and become more relevant under extreme or prolonged conditions.

Gender Differences in Salt Loss and Retention

Biological sex plays a measurable role in how salt is lost, conserved, and distributed throughout the body. These differences are driven by physiology, hormones, and body composition, not just behavior or diet.

-

Men tend to lose more salt through sweat. They typically have more active and densely distributed sweat glands than women, leading to higher fluid and sodium loss during equivalent levels of exertion. This difference becomes even more pronounced in heat, during heavy labor, or prolonged exercise.

-

Women often retain sodium more efficiently. Hormones like estrogen and progesterone influence how the kidneys filter and reabsorb sodium, making women somewhat more resistant to sodium loss under normal conditions. However, this advantage can shift depending on menstrual cycle phase, pregnancy, or use of hormonal contraception.

-

Body size and muscle mass affect fluid and salt turnover. On average, men have higher muscle mass and larger total body water volume, which leads to greater baseline demand for salt to maintain fluid balance, circulation, and thermoregulation.

Understanding these gender-based physiological differences can help explain why salt needs and responses to low-salt diets may vary significantly between men and women. What’s considered “high” or “low” salt intake on paper doesn’t mean the same thing in different bodies. Context matters.

Ethnic Differences in Salt Metabolism

Salt needs and sensitivity aren't the same for everyone. Genetics, environment, and evolutionary history all shape how different populations handle sodium and chloride. These differences help explain why some groups are more salt-sensitive, retain sodium more easily, or face higher risks of hypertension on low- and high-salt diets:

-

African-Americans. Studies suggest that people of African descent have a greater tendency to retain sodium from evolutionary adaptations to hot, arid environments where conserving salt and water was critical for survival. This physiological trait has been proposed as one factor contributing to the higher rates of hypertension observed among African-Americans compared to other ethnic groups. However, alongside diet, socioeconomic stress, poor access to healthcare, and other systemic factors, it is only one of the variables that influence cardiovascular risk.

-

People of East Asian descent often need less salt to meet their basic needs, and some may be more sensitive to it, meaning their blood pressure can rise more noticeably when they eat salty foods. This sensitivity affects how their cardiovascular system reacts to salt, not how much salt they actually lose.

-

Caucasians and Northern Europeans tend to have higher sweat rates in general, which may contribute to slightly greater salt and water loss under heat or exertion.

These differences matter most when interpreting salt needs for individuals, especially in contexts like heat exposure, athletic training, or recovery from illness. But day-to-day, environment, activity level, and diet remain the dominant factors.

Daytime Losses

Yes, there is a clear difference in salt and water loss between day and night, driven by changes in activity level, body temperature, hormonal rhythms, and environmental exposure.

Most salt loss occurs during the day, especially during physical activity and exposure to heat, which raises body temperature and increases sweating. Here are the main contributors:

-

Intense work, exercise, or sports, especially outdoors in hot or dry climates. Physical exertion drives up thermogenesis and activates sweating, which accelerates salt loss. Even short sessions can lead to significant depletion if not replenished.

-

Exposure to heat, whether from outdoor weather or indoor environments. Higher ambient temperatures increase perspiration, even when you're not visibly sweating. Dry air speeds up evaporation and masks the true extent of fluid and salt loss.

-

Eating and drinking stimulate digestion, which increases salt demand. Digestive juices—especially stomach acid—require large amounts of sodium and chloride. A high-protein meal, for example, draws even more salt from the bloodstream to support acid production.

-

Daytime hormonal patterns increase salt excretion in urine. Hormones like aldosterone and cortisol are naturally higher during the day and promote sodium loss through the kidneys. This is part of the body’s circadian rhythm, not necessarily a sign of excess.

The only real defense against these daytime losses is adding salt back in. Indigenous people who live in high-altitude regions with dry air often drink tea with salt, not sugar—a habit shaped by necessity, not taste.

Nighttime Losses

At night, the body enters a fluid-conservation mode, reducing urine output and slowing electrolyte loss. But water is still lost through breathing, sweating, and metabolic activity, including tissue repair and detoxification.

-

Sweat and respiratory salt losses drop sharply during sleep. As body movement decreases and core temperature cools, the body produces less sweat, and breathing slows down. With less evaporation through the skin and lungs, fewer electrolytes are lost overnight compared to daytime activity.

-

The body enters a conservation mode to slow the loss of fluids. This includes reduced blood flow to the skin and gut, decreased thermogenesis, and lower metabolic demands. Together, these changes minimize the need for salt and water, helping to preserve internal balance while you sleep.

-

Urine production drops due to the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH). ADH rises at night, concentrating urine and reducing overall output. This is why most people don’t need to urinate during a full night’s sleep—and why urine is usually darker in the morning.

-

Salt loss through the kidneys is also reduced overnight. With less sodium filtered and excreted, the body holds on to salt more efficiently. This pattern is part of the circadian rhythm and is designed to prevent dehydration while you’re asleep and not eating or drinking.

By morning, most digestive fluids have been reabsorbed, and plasma sodium chloride may become more concentrated. So waking up thirsty is often the result of overnight metabolic demands, extra sweating in dry or warm climates, and the increased concentration of reabsorbed salt.

Salt Loss in Children

Before puberty, children have significantly fewer active sweat glands, and their thermoregulatory systems are not yet operating at full adult capacity. This is why children may tolerate heat differently and are less prone to the same degree of salt depletion, though their smaller fluid reserves make them more vulnerable to dehydration overall if vomiting or diarrhea is involved.

Induced (Lifestyle-Related) Losses

The induced losses of salt result from the choices you make. My goal here isn't to make you change your lifestyle, but to make you aware of which of them may negatively impact your health. If any factor listed below is present in your life, make sure to offset it with an extra bit of salt:

-

Overhydration. Excessive intake of low-mineral water dilutes blood sodium levels and triggers a diuretic response. The kidneys excrete both water and salt to maintain homeostasis, leading to hidden salt depletion even without thirst.

-

Hyperinsulinemia (from sweetened and refined foods). Chronically high insulin levels promote loss of salt in the urine, particularly in people with insulin resistance. This is a hidden cause of low blood volume and fatigue in carbohydrate-heavy diets.

-

Caffeine acts as a mild diuretic, especially when consumed in large amounts without food. This accelerates urinary loss of both water and electrolytes, including salt, particularly in people not accustomed to caffeine.

-

Alcohol suppresses antidiuretic hormone (ADH), increasing urination and promoting the loss of salt and other electrolytes. Even modest alcohol intake can dehydrate the body and disrupt salt balance, especially when combined with physical activity, heat exposure, or both.

-

Low-salt, high-water diets. Consuming mostly fruits, vegetables, and grains while drinking large volumes of water can result in ongoing salt depletion, even with adequate calorie intake.

-

Salt-potassium imbalance. When potassium intake is high (from fruits, vegetables, supplements) and salt is low, the body increases its excretion to maintain electrolyte balance, often leading to chronic salt loss.

-

Endurance exercise without salt replenishment depletes salt stores. Replacing only water without salt leads to hyponatremia, or a drop in blood salt levels, and causes fatigue, muscle cramps, or confusion.

-

Sauna Use. Exposure to the sauna for 20–40 minutes can result in significant salt and water loss through sweat. Replenishment with only water increases the risk of dilutional hyponatremia.

-

Fever and Inflammation. Infection or systemic inflammation raises fluid turnover and alters renal sodium handling, increasing salt and water losses, even at rest or during mild illness.

-

Medications. Drugs such as diuretics, metformin, antidepressants (SSRIs), blood pressure meds, and antiepileptics can promote salt loss either directly or through secondary effects on fluid balance.

-

Dry Indoor Air / Air Travel. Low humidity in heated or air-conditioned environments and airplane cabins increases insensible water loss through respiration. Salt is lost indirectly through increased urine volume and dehydration.

This list is far from complete, but with everything you have already learn, sufficiently representative.

Digestive and Systemic Signs of Salt Deficiency

As you can see from everything said above, the number of factors that influence salt deficiency is immensely varied. Even a super-duper A.I. would have a hard time handling personalized recommendations day after day, month after month, year after year. In a pickle like this, just fall back on the time-tested approach: listen to your body and adjust accordingly. Two or more of the following symptoms will usually tell you with a reasonable degree of certainty that your salt levels are too low:

-

Wedding band test. If your ring suddenly feels loose or slips off more easily than usual, you may be low on salt. As sodium levels drop, blood volume contracts and fluid shifts out of tissues, causing a subtle shrinking in the fingers. It is an everyday sign that your salt levels might be too low, especially when it happens alongside other symptoms below.

-

Salt cravings. Often, the earliest and most direct signal. When salt levels drop, the brain responds by driving you to seek it out, sometimes subtly, sometimes obsessively.

-

Loss of appetite. A very common early sign, linked to reduced stomach acid. Without enough salt, the digestion process starts sluggish, and hunger fades.

-

Nausea, bloating, and indigestion. As stomach acid and digestive enzymes decline, food digestion slows, leaving you feeling overly full, gassy, or slightly nauseous.

-

Constipation, hard and dry (pebble-like) stools. Reduced sodium means less water in the stool and slower intestinal movement. This shows up quickly, especially in people already prone to bouts of constipation.

-

Fatigue and low energy. As sodium drops, so does blood volume. Circulation becomes less efficient, leading to a sense of heaviness and low physical stamina.

-

Mental fog, confusion, or irritability. A common follow-up from low energy and poor circulation. Reduced sodium also impairs neurotransmission, making it harder to think clearly or stay emotionally steady.

-

Dry mouth and dry skin. These signs of dehydration can show up even when you're drinking enough water, but your salt intake is too low to retain it. Without salt, much of that water simply passes through you instead of hydrating tissues.

-

Low urine volume, frequent urges, or abnormal urination. When salt levels drop, the kidneys struggle to balance fluids properly. You may urinate less overall, but still feel frequent urges due to bladder irritation or poor fluid distribution. In some cases, urine becomes overly concentrated, dark, or foul-smelling. These shifts often reflect the body's attempts to conserve salt and water, but not doing it efficiently.

-

Lightheadedness or dizziness when standing up quickly. It’s a common sign that your blood pressure is too low to reach your brain quickly. This condition tends to happen when salt levels are low or you're losing too much fluid and salt through sweat or urine.

-

Headaches. Salt deficiency doesn’t cause headaches in isolation, but it contributes through low blood pressure, dehydration, and poor circulation, all of which are well-established headache triggers.

-

Muscle cramps or weakness. A sign of disrupted nerve signaling and electrolyte imbalance, more likely with physical exertion, heat, or additional mineral deficiencies (like magnesium or potassium).

-

Gastroparesis (delayed stomach emptying). Low salt levels reduce stomach acid and weaken nerve signals that control digestion. This condition slows down how quickly food leaves the stomach, leading to fullness, bloating, nausea, or vomiting. Gastroparesis is common in people with diabetes and preexisting stomach disorders, but salt deficiency makes it even worse.

-

Low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria). This symptom is often the underlying driver of many earlier symptoms, but as a clinical condition, it takes time to develop and detect. It leads to deeper problems like gastroparesis, foodborne infections, and nutrient malabsorption over time.

In severe cases, such as in hospitalized patients or endurance athletes, salt deficiency can lead to seizures, coma, or death due to cerebral edema. But even mild chronic deficiency can quietly undermine digestion, energy, and hormonal stability.

So, by now, you know what to watch for when salt levels drop too low. Now let’s flip to the opposite side of the dark moon and look at the equally serious risks of getting too much salt.

Warning Signs of Excessive Salt Intake

Symptoms of excess salt intake are less straightforward because, in healthy individuals with normal kidney function, the body efficiently excretes excess sodium through urine and sweat. However, when intake consistently exceeds the body's capacity to regulate, or in the presence of underlying health conditions, certain signs may emerge.

Here's a list of the most common functional and clinical signs of salt excess. These conditions aren't exclusive to salt, so you should only consider them after knowingly consuming significantly more salt than recommended:

-

Wedding band test. If you can’t slip off your ring, or it feels tighter than usual, you’re likely holding onto too much fluid due to excess salt. Fingers are one of the first places where fluid retention shows up. This subtle sign often appears before swelling becomes obvious elsewhere. It’s a practical, everyday indicator that your salt intake may be running too high.

-

Swelling (edema). Fluid retention is one of the clearest signs of excess salt intake. The body holds onto water to dilute the extra sodium in circulation, leading to visible swelling in the hands, feet, ankles, face, and, less commonly, in soft tissues like the scrotum (testicles) and female breasts.

-

Puffiness under the eyes. A subtle but common sign, especially in the morning. This kind of facial bloating often reflects overnight salt retention combined with lying flat, which redistributes fluid toward the head and face.

-

Thirst and dry mouth. High salt concentration in the blood triggers your thirst mechanism as the body tries to correct the imbalance by diluting sodium levels. If you've been eating very salty foods, you may feel thirsty even if you've been drinking normally.

-

Frequent urination. The kidneys try to flush out excess sodium by increasing urine production. This compensatory response can make you urinate more often, especially after a salty meal, and may lead to temporary dehydration if not balanced with adequate water.

-

Headaches. Rapid shifts in sodium levels or fluid distribution can cause headaches. These are usually mild but may feel like tension or pressure headaches. Dehydration, even short-term, can also contribute.

-

Irritability or restlessness. Electrolyte imbalances can affect nerve function and mood. When sodium levels spike too high, you may feel wired, edgy, or unusually irritable—especially if it's combined with poor sleep or caffeine.

-

Short-term weight gain. Excess sodium causes water retention, which shows up on the scale quickly, even overnight. This is not fat gain but a temporary increase in water weight that reverses once sodium levels normalize.

Boxers and jockeys use saunas or hot baths to shed excess water and salt before weigh-ins. The heat drives fluid out through sweat, which pulls sodium and other electrolytes with it. It’s a quick and effective way to drop 'water' weight fast. While not sustainable or even entirely safe, this technique shows just how responsive the body is to salt-driven fluid shifts. So, if you find yourself bloated after a night of binging on beer and pretzels, it is a reliable way to get back into 'fighting' shape quickly.

Most of the symptoms listed above result from chronic salt excess in people who have compromised kidney function. In contrast, acute salt overload from consuming large quantities of salt in a short period can trigger vomiting, diarrhea, or confusion as the body tries to expel the excess and restore balance rapidly. These reactions are protective but can lead to dangerous fluid and electrolyte imbalances if not corrected quickly. I wrote extensively about this situation in the Why Do People Throw Up When They Are Too Happy, Too Angry, or Too Scared? essay.

For healthy individuals with balanced hydration and normal kidney function, the body is remarkably efficient at managing salt fluctuations through thirst, urine output, and hormonal regulation.

What about me?

So, how much salt should you actually consume? That's the question everyone wants answered, and the one I can't answer with a one-size-fits-all number or formula because:

Salt needs vary widely from person to person depending on body size, age, diet, activity level, health status, medications, and dozens of other factors I've already described above.

Just as important, they also vary from day to day. You might need twice as much salt on a hot, stressful, active day as you do working from home in an air-conditioned room. Travel throws things off. Weekends throw things off. Changes in sleep, diet, exercise, alcohol, and caffeine—all of them shift your needs.

So no, I can't give you a magic number. And if I did, it wouldn't serve you well. The only way to get this number right is to listen to your body and adjust accordingly. That's why I outlined the signs of salt deficiency and excess above, so that you can observe and recognize them early, before any problems, too much or too little, set in.

If you pay attention to your body's signaling, it will tell you exactly when it needs more salt or less. You just have to stop ignoring the signals or living in fear of "overdosing."

Let's Wrap it Up!

If you've made it this far, one thing should be clear: salt is not a ‘white death’ toxin, but an essential nutrient. Like all essentials, the real harm comes not from occasional excess but from continuous deficiency. The symptoms of too little or too much salt are clear when you know what to look for. And, by now, you do!

I am not asking you to go wild on salt, but reminding you to stop fearing what your body needs. Listen to it. Watch for the signals. And don't allow obsolete guidelines to ruin your health.

Author's note

Just like with low-salt diets, the history of public healthcare in the United States is littered with sacred cows: low-fat diets, cholesterol phobia, dietary fiber, eight glasses of water, an apple a day, and others. These ideas persist not because they’re right, but because they’re profitable:

-

Low-fat diets gave us skim milk and dairy creamers. Skim milk (technically whey) is a byproduct of butter and cheese production. It used to be sold to farms to feed calves or flushed down the drain. Once repackaged as a health food, it turned waste into revenue. What began as a way to offload leftovers is now an $82.4 billion global industry justified by a shaky link between fat and heart disease.

-

The cholesterol craze gave us margarine. To replace butter, food manufacturers began hydrogenating cheap vegetable oils to make margarine—an artificial fat loaded with trans fats and oxidized compounds. It's exceptionally toxic for the heart and brain, but incredibly cheap to produce. At its peak, margarine was a $25 billion industry. The broader anti-cholesterol campaign also propped up statin drugs, now a $16,6 billion global market, with neurological side effects (dementia, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's diseases) that outweigh the conditions they're prescribed to treat.

-

Eight glasses of water gave us a huge bottled water industry. This myth turned tap water into a premium product. Most bottled water is filtered tap or groundwater resold in plastic bottles for more per gallon than gasoline. It became a $348 billion global business. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions are now overhydrated, salt-deficient, chronically fatigued, and prematurely aged.

-

The "apple-a-day" dogma paved the way for the fruit and juice industry. This slogan helped rebrand sugar-laden products as health foods. Pediatricians now see toddlers with fatty liver disease, driven by fruit pouches and juice boxes. The fresh fruit and juice market exceeds $95 billion, but the downstream cost is far greater: more than 100 million Americans live with prediabetes or diabetes, sustaining a $500 billion-plus part of the healthcare industry focused on managing blood sugar, obesity, and their side effects.

-

The dietary fiber cult gave us morning cereals. What began as a fringe obsession with "colon cleansing" became a breakfast empire. Processed grains, fortified with synthetic vitamins, are sold as high-fiber health foods—even though they spike blood sugar, inflame the gut, and provide little usable nutrition. The global breakfast cereal market now exceeds $49 billion, dominated by products that were once classified as desserts.

And who benefits from the low-salt craze? Considering the cascade of disorders it sets in motion, it isn't difficult to figure out either.

Thanks for listening!

Please share this post with your family and friends to support my work!

Thank you!

Konstantin Monastyrsky