How to Self-Diagnose Trace Mineral Deficiencies

This article provides a detailed overview of trace minerals' role in your physiology and their impact on your health, aging, and chronic diseases. Practically every misery on display in the Emergency Room of any hospital can be, pun intended, traced back to one or more of those missing trace minerals.

Knowing more about them and applying this knowledge to your own nutrition will pay you back in a longer and healthier life with minimal effort and for less money over your lifetime than the cost of a single emergency room visit.

The term "trace" in “trace minerals” refers to iron, zinc, copper, boron, selenium, iodine, manganese, chromium, and molybdenum because they are present in less than 0.01% by volume in your body. The other commonly used terms are trace minerals, microelements, and microminerals on their own or with the word "essential" in front of them.

This table shows the approximate quantities of trace minerals and their percentages of the total body weight of a 155 lb (70 kg) individual:

| Trace Mineral | Symbol | Amount (Mg) | %% of Body Weight |

| Iron | Fe | 3500 | 0.005000% |

| Zinc | Zn | 2500 | 0.003571% |

| Copper | Cu | 100 | 0.000143% |

| Boron | B | 18 | 0.000026% |

| Selenium | Se | 15 | 0.000021% |

| Iodine | I | 15 | 0.000021% |

| Manganese | Mn | 12 | 0.000017% |

| Chromium | Mn | 6 | 0.000009% |

| Molybdenum | Mo | 5 | 0.000007% |

Despite their tiny amounts in the body, all of them participate in biochemical reactions and physiological processes that manage critical body functions, and are just as important for life and health as better-known calcium, magnesium, or potassium.

If you're curious how these values were determined, here's a brief explanation. One of the most accurate methods involves complete cremation (also called ashing) of cadavers. To ensure the ash isn’t contaminated with mercury, gold, steel, titanium, or other materials from dental work and implants, the body is X-rayed, and all foreign objects are removed before cremation.

What's left is chemically analyzed using mass spectrometry to quantify trace minerals. These values are then averaged and scaled by body weight and sex to estimate total body content for each trace mineral. It's gory, but accurate to a milligram.

Physiological Functions of Trace Minerals

Getting enough trace minerals in the past wasn't as problematic as today because everyone was drinking raw water and eating foods grown in virgin soil. Not anymore for urban Americans.

Here is a brief outline of the trace minerals’ key roles. The more you understand their functions in your health, the easier it is to grasp their importance in prevention. So, here we go:

-

Cofactors in Enzymatic Reactions. Enzymes are biological catalysts that drive the chemical reactions essential for your metabolism. Metabolism refers to processes that convert nutrients into energy, synthesize structural and functional molecules, support cell division, and eliminate waste byproducts.

Many enzymes require trace minerals as cofactors to function properly. A shortage of these elements disrupts energy production, cellular maintenance, and tissue renewal — the core functions of life. This process is what turns flourishing young men or women into proverbial ‘old bags.’

-

Immune System Support. Your body depends on trace minerals for the development and function of immune cells. A lack of zinc or selenium, for example, impairs wound healing and increases susceptibility to infections. Restoring adequate levels through supplementation improves immune responses and lowers infection risk.

If you are deficient in key vitamins or trace minerals, milk composition may be suboptimal even in the mature stage. Many women in the United States are, because carrying a baby to term takes a tremendous amount of nutritional resources, rarely supported by a proper diet or supplements.

The whole turnaround takes nearly a month during the most critical phase of infant development. It’s far smarter to take a quality supplement throughout pregnancy than to roll the dice on your baby’s future health.

Cellular Protection. Trace minerals support enzymes responsible for removing metabolic waste and damaged molecules from cells. Selenium, zinc, copper, manganese, and iron, for example, are essential for enzyme systems that break down harmful byproducts and maintain the internal environment needed for orderly cell function.

These processes help prevent the buildup of cellular debris that interferes with normal cell division and tissue renewal. Even minor deficiencies of these elements can impair enzyme efficiency, slow the removal of waste, and disrupt the division cycle.

The medical authorities in the United States cry wolf about all kinds of cancers becoming ‘younger’ by the day. In fact, that is a direct outcome of trace minerals ‘missing in action.’ There is nothing more shortsighted than refusing to keep your trace minerals current with a basic supplement and getting hit with deadly cancer.

Gene Regulation. Trace minerals contribute to structural integrity and the regulation of genes. Here are a few examples: Zinc stabilizes the structure of thousands of genetic transcription factors via “zinc finger” domains. Copper and manganese support the synthesis of collagen, elastin, and bone formation. Molybdenum and magnesium assist with various cellular enzymes.

When working together, trace minerals ensure normal growth, neurological function, hormone activity, and tissue maintenance. And when not, your health goes down the drain over what could have been easily prevented with a basic supplement.

Energy Production. Trace minerals are essential for generating energy at the cellular level. Iodine is a key part of T3 and T4 thyroid hormones, which regulate metabolic rate. Iron, copper, and manganese are required for mitochondrial enzymes that produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the body’s energy currency. Magnesium and zinc support glycolysis (the conversion of glucose into ATP) and the Krebs cycle (the conversion of other nutrients into ATP).

Even minor trace mineral deficiencies can stall these metabolic reactions, leaving cells underpowered and tissues starved for energy. This is one reason why people with deficiencies complain of low energy and chronic fatigue. Just like you can’t run a premium car on low-octane gasoline, your body can’t function properly on a diet depleted of trace minerals, no matter how many ‘calories’ it provides.

So, when you see a 70-plus-year-old man like me still moving like a spring chicken while most of my contemporaries drift in a semi-lethargic state, it isn’t genetics or luck, but my trace mineral status.

Vascular, Heart, and Brain Health. Trace minerals are critical for heart and brain function. Selenium, for example, is required for cardiac muscle protection. Even mild selenium insufficiency has been associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease. Zinc plays a role in modulating blood pressure and in preventing atherosclerosis by reducing inflammation and modification of lipids. Copper is needed for heart structure and angiogenesis.

And whenever the blood vessels of the heart are at risk, so are the blood vessels of the brain. Not surprisingly, just like with cancers, heart disease and strokes are becoming ‘younger’ too. Here is what concerned epidemiologists wrote almost a decade ago:

“Current observations might, therefore, be used to forecast a potential epidemic of cardiovascular disease in the near future as the younger segment of the population ages. In this Review, we discuss the burden of risk factors for ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death among young adults aged 18–45 years.” Andersson, C., Vasan, R. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in young individuals.

If younger people are getting sicker by the day, imagine how much greater the risks are for the 50-plus crowd.

Metabolic and Endocrine Regulation. Several trace minerals are involved in glucose and lipid metabolism, linking them to conditions like type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, or a group of conditions that include hypertension, high blood sugar, weight gain, and atherosclerosis.

Chromium supports insulin signaling and may help regulate blood sugar. Zinc, along with magnesium (not a trace mineral), is also essential for insulin production and action. Deficiencies in either can increase the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Iodine deficiency can cause hypothyroidism and goiter, while even mild deficiency during pregnancy may affect brain development in children. Selenium also supports thyroid function by activating thyroid hormones, and low selenium levels are associated with thyroid dysfunction.

Ensuring sufficient intake of these trace minerals is an important preventative measure against metabolic and endocrine disorders.

Dementia and Memory Loss. Zinc, copper, and selenium are essential for brain function. Zinc and copper support neurotransmitter synthesis, while selenium is required for enzymes involved in neuronal maintenance. Deficiencies in these elements have been linked to impaired cognitive performance and a higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

Low selenium has been connected with cognitive decline and may contribute to conditions like Alzheimer’s. It supports enzymes involved in maintaining and repairing neurons, and without enough of it, those systems don’t work as well.

Zinc is necessary for memory formation. Chronic zinc deficiency in older adults has been linked to cognitive impairment and may worsen age-related conditions such as macular degeneration and neurodegeneration. Ensuring adequate intake of zinc and selenium is important for maintaining cognitive health with age.

Cancer. Adequate intake of selenium and zinc can protect DNA from damage, potentially lowering mutation rates and cancer risk. Selenium in particular has been studied for its cancer-preventive potential; some studies showed a lower incidence of certain cancers with selenium supplementation.

Longevity and Quality of Life. Trace mineral status may influence not only longevity but also the period of your life free from chronic diseases. Ensuring optimal intake of trace minerals helps preserve physiological stability, delay functional decline, and extend the years lived in good health.

Premature Aging: As you age, your levels of trace minerals go down because of decreased digestion, absorption, metabolism, and medications. Resulting deficiencies reduce your body’s ability to remove cellular waste, disrupt tissue maintenance, and interfere with cell renewal. All of these factors combined accelerate frailty and age-related decline.

You got a good idea what's at stake, right?

In that case, please take a closer look at each trace mineral — what it does, where it comes from, what happens when it’s missing, and how to keep up adequate levels through diet or supplementation. None of this is complicated, but frequently overlooked, and the cost of that omission gradually undermines your health and vitality.

I'll begin with iron, the best-known among all other trace minerals, because iron makes the blood red. And despite its tiny amount in the body, just under five grams, iron plays an outsized role in our lives. Describing iron in depth will take the rest of this page. I'll address the remaining trace minerals in the next article.

The greatest challenge with iron is that your levels may appear perfectly normal on routine blood tests, but you may still have anemia, and there’s more than one kind.

By the end of this page, you will learn about 12 types of anemia, 37 iron deficiency disorders, 24 risk factors for low iron, 7 cofactors needed to turn iron into hemoglobin, 9 steps to overcome deficiency, read answers to 23 frequently asked questions about the love-hate relationship between iron and anemia, and find out why the “deep state” doesn’t want you to know any of this information.

Iron Deficiencies

None of the trace minerals is as foundational to health as iron because every single red blood cell uses it to carry oxygen to every other cell of the body. Despite iron's outsized role, you probably know very little about it. If this were otherwise, one-half of American women between 18 and 50 wouldn't be iron-deficient, and 1 in 36 children born in the United States wouldn't have autism.

You've probably seen it in movies or read in spy novels about potassium cyanide, the near-instant poison that spies use to kill themselves to avoid torture. One tiny drop is all it takes. Within minutes, cyanide shuts down the body’s ability to use oxygen even when it’s plentiful, and there is no way to undo it with an antidote.

Not having enough iron to carry oxygen around the body is like taking a microdose of cyanide. Not enough to kill you, but enough to keep every system running half-awake: the heart, the brain, the immune system, the muscles, everything drops into low power mode without enough oxygen.

So if you lack energy, or your memory slips, or the mood for work isn’t there, and you suspect iron deficiency, and ChatGPT has confirmed a bunch of other symptoms, and you get the highest-rated iron supplement from Amazon, but somehow, it doesn’t help. What gives?

Actually, there are two kinds of iron deficiency: absolute and functional.

Absolute iron deficiency means that your blood test has shown that the amount of iron stored in your body is well below normal. This type of deficiency is caused by a multitude of factors described in this article.

Functional iron deficiency means that, according to the blood test, iron stores appear normal, but the iron can’t be utilized by red blood cells. In other words, you may have a perfect diet, take perfect supplements, and have all the iron your body needs already there, but still suffer from iron-deficiency anemia.

How common is it?

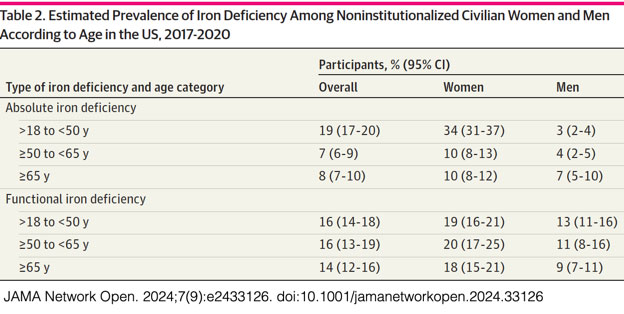

Very common, actually. According to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, among women between 18 and 50 years of age, 34% had clinically significant absolute iron deficiency and 19% had functional iron deficiency. Functional iron deficiency was more common than absolute iron deficiency in all age and sex categories except women younger than 50 years [link].

This research was conducted with 8021 adults between 2017 and 2020, and data analysis was performed from March 21, 2023, to July 5, 2024. It excluded pregnant women, people with cancer, kidney disease, or heart failure, the very groups most prone to iron deficiency.

Since the study does not indicate overlap between absolute and functional deficiencies, and functional deficiency can only occur in people with ‘normal iron’ stores, the combined iron deficiency prevalence may be as high as 53% (34% + 19%), or every second woman in the United States.

The figures for men and older adults weren’t as dramatic, but neither encouraging. This table comes directly from the study:

By not “as dramatic,” I mean that the combined risk for iron deficiency in men in the 18 to 50 age group is 16% (3% + 13%), but if you are in that 16% category, a ‘shit storm’ is still in the cards for you, and one must be a reckless fool to ignore it.

The situation for men and women over 50 isn’t much better. 30% combined for women between 50 and 65, and 28% for women over 65. Men are somewhat better: 15% combined between 50 and 65, and 16% over 65.

If we go by our cyanide analogy, having 30% or 15% less energy at any age isn’t such a great option either when considering all other aches, pains, and indignities that come with age.

Fortunately, with the right know-how, you can correct absolute and functional iron deficiencies in a few months, as well as prevent them from ever happening to you again.

With that in mind, I wrote this article, the first in a series about essential trace minerals.

How Much Iron is in the Body?

The average adult body contains around 4 grams of iron, most of it incorporated into hemoglobin within red blood cells. Smaller amounts are stored as ferritin in the liver, bone marrow, and spleen. Some iron is also held as hemosiderin in tissues, but this is not measured in routine blood tests. Iron stores are assessed through serum ferritin and referred to as ‘absolute iron,’ as described above.

Iron is required for synthesizing hemoglobin, which, in turn, carries oxygen in red blood cells, and myoglobin, which stores oxygen in muscle tissue. It also supports cellular energy production, immune system activity, neurotransmitter synthesis, and cognitive development throughout life.

Where Does the Iron Come From?

Dietary iron is present in meat, poultry, fish, and shellfish as heme iron, and as non-heme iron in plant-based foods. The term "heme" refers to the iron component of hemoglobin, a protein containing iron that transports oxygen in red blood cells.

Heme protein is synthesized in the bone marrow and the liver of all humans and animals, and it is the most ‘bioavailable’ form of iron, meaning easily absorbable in the small intestine.

It’s important to understand that dietary iron doesn’t exist in the same elemental form as it does in steel pans or cast iron pipes. In food, water, and supplements, iron exists as ions, typically in one of two charged states: Fe²⁺ (ferrous) or Fe³⁺ (ferric). These notations refer to iron atoms that have lost two or three electrons, giving them a positive charge:

1. Ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) – the soluble, plant-available form;

2. Ferric iron (Fe³⁺) – the oxidized, insoluble form;

3. Chelated iron (Fe²⁺ or Fe³⁺ bound to organic molecules);

4. Ferritin ( Fe³⁺) – a protein that stores iron inside cells in humans, animals, and plants.

5. Heme iron (Fe²⁺) – as found in blood and explained above.

Tap water may contain iron from iron pipes or iron-rich soil in the first and second forms.

Americans are expected to get their daily fix of iron from fortified wheat in bread, pasta, and cereals and fortified white rice. That iron comes in the second form.

None of what I described above is particularly new or unknown to concerned parents or to anyone who attended medical school in the past 150 years. When I was a toddler in the late 1950s, my mother would get me a sweet candy bar from the local pharmacy called “Hematogen” ("Гематоген" in Russian).

This concoction was made from processed cow’s blood mixed with condensed milk, sugar, and vitamin C. The original formula under the same name was developed by Dr. Adolf Hommel in Switzerland and marketed in a liquid form since the 1890s. It became widely produced in the Soviet Union starting in the 1920s.

I kept eating Hematogen occasionally well into my teens. That's how dirt-poor Soviets maintained a reasonably healthy population. Americans didn't need Hematogen because throughout most of the twentieth century, red meat was cheap, plentiful, widely consumed, and considered a "health food."

All that changed when, in the 1980s, health authorities began vilifying red meat (a source of essential amino acids, protein, iron, folate, B-12, and zinc), table salt (a source of chloride and iodine), and butter (a source of essential fatty acids). During that time, the rate of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) was just 1 in 2,500 (0.04%).

Two generations later, 1 in 36 (2.8%) children are diagnosed with ASD, driven in part by maternal deficiencies in all of the above nutrients during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Two other contributing factors throughout these most vulnerable stages of fetal and infant development include exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in food and heavy metals in drinking water and dental amalgams.

I discuss numerous other contributing causes of ASD throughout the site. Please use the "Autism" keyword to search for this topic.

Not All Anemias Are the Same

It may surprise you, but iron deficiency and anemia are not synonyms. Many types of anemia aren't caused by low iron. So...

Anemia is a blood disorder characterized by a deficiency of red blood cells (erythrocytes) or reduced levels of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying molecule inside erythrocytes. Some types of anemia also involve abnormal morphology (form, structure, and appearance) of erythrocytes or structurally defective hemoglobin.

The primary role of normal erythrocytes is to transport oxygen from the lungs and remove carbon dioxide. When this function is impaired, the body becomes deprived of oxygen—a critical element for cellular energy metabolism.

A person with anemia finds themselves in a state similar to a mountain climber in thin air at 5,000 to 6,000 meters above sea level. This condition is known as hypoxia. The symptoms are similar: apathy, fatigue, drowsiness, and depression. In climbers, these symptoms subside once they descend. People with anemia, however, have no such escape.

In response, the body activates compensatory mechanisms: rapid breathing, elevated heart rate, and increased blood pressure. This prolonged strain on the cardiovascular system to deliver oxygen-poor blood can contribute to heart disease, stroke, and early mortality.

Red blood cells also help buffer blood pH and transport nutrients like lipids and amino acids that support cell division, hormone production, and neurotransmitter synthesis.

Chronic anemia limits oxygen delivery, disrupts cell metabolism, and often coexists with broader nutrient deficiencies. It contributes to the progression of many chronic conditions, including fatigue, hair loss, cardiovascular disease, low physical endurance, infertility, immune dysfunction, depression, and developmental delays in children.

This article addresses primarily iron-deficiency anemia, the dominant kind and usually defined by absolute iron deficiency. Non-iron anemias are functional, infectious, autoimmune, congenital, or malignant and are not caused by absolute iron deficiency. They include:

Megaloblastic anemia. Caused by a deficiency of vitamin B-12 or folate. Characterized by large, immature red blood cells.

Pernicious anemia. A type of megaloblastic anemia that is caused by impaired absorption of vitamin B-12, often from a lack of intrinsic factor.

Hemolytic anemia. Caused by the premature destruction of red blood cells. May be congenital (e.g., sickle cell, thalassemia) or acquired (e.g., autoimmune).

Aplastic anemia. Caused by bone marrow failure to produce enough blood cells. May be idiopathic, drug-induced, or due to toxins/radiation.

Sideroblastic anemia. Iron is present but not properly incorporated into hemoglobin. It can be congenital or caused by alcohol, drugs, or lead poisoning.

Anemia of chronic disease (inflammation). Iron is present but sequestered and unavailable for use. Often seen in chronic infections, autoimmune disorders, or cancer.

Anemia of kidney disease. Caused by reduced erythropoietin production, leading to inadequate red blood cell production.

Thalassemia. Inherited disorder affecting hemoglobin synthesis. Includes alpha and beta types.

Sickle cell anemia. Inherited condition with abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) that distorts red blood cells into a sickle shape.

Many blood cancers can manifest themselves as anemia long before other signs of malignancy are apparent. This is especially true for:

Leukemia. Cancerous white blood cells crowd out red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow, leading to decreased red blood cell production.

Lymphoma. Some lymphomas infiltrate the bone marrow or disrupt erythropoiesis through cytokine-mediated inflammation.

Multiple myeloma. Abnormal plasma cells in the marrow suppress normal red blood cell formation.

Each of these conditions has distinct causes, mechanisms, and treatments unrelated to diet or supplementation. When confronted with anemia, you must be extra careful with throwing at it iron supplements to avoid associated toxicities from iron overload. Your best form of protection is lab work, as described in the How to Confirm Absolute and Functional Iron Deficiency section.

Iron-deficiency disorders

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Classic Anemia. The hallmark outcome of chronic iron depletion. Characterized by reduced hemoglobin synthesis, resulting in fatigue, pallor, shortness of breath, dizziness, and poor exercise tolerance.

Microcytic Hypochromic Anemia. Because of insufficient hemoglobin, red blood (erythrocytes) cells become smaller (microcytic) and paler (hypochromic).

Reduced Red Blood Cell Count. Even before full anemia develops, iron deficiency may lower erythropoiesis (creation of erythrocytes) and reduce hematocrit (percent of erythrocytes in the blood).

Miscellaneous Conditions

Headaches and Dizziness. Poor oxygen delivery can trigger vascular headaches or lightheadedness, especially with exertion or position changes.

Tinnitus. Iron-deficiency anemia has been associated with ringing or buzzing in the ears in some individuals.

Depression and Anxiety. Iron is required for the synthesis of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters regulate mood, focus, and emotional stability. Low levels of iron disrupt their balance. Deficiency does not cause mood disorders directly, but it amplifies their symptoms in women and adolescents.

Restless Leg Syndrome. Low brain iron stores are strongly associated with this sensory-motor condition, marked by an uncontrollable urge to move the legs, especially at night.

Pica. Craving and consumption of non-food substances—most commonly ice (pagophagia), but also dirt, clay, or paper—is strongly associated with iron deficiency.

Inflammatory Conditions

Impaired Immune Function. Iron is required for neutrophil and lymphocyte activity. Deficiency increases the risk and severity of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

Altered Inflammatory Response. Low iron may interfere with normal cytokine regulation and weaken mucosal defenses.

Glossitis. Inflammation, swelling, or smoothness of the tongue may point to moderate to severe deficiency.

Skin, Hair, and Nail Conditions

Hair Loss. Iron deficiency is one of the most common nutritional causes of diffuse hair shedding, especially in women. It disrupts the hair growth cycle by putting hair follicles into a resting phase, increasing daily loss, and reducing regrowth. It may be exacerbated by vitamin deficiencies described in the related section.

Koilonychia. Also called “spoon nails,” or thin, concave, brittle nails that result from a long-standing iron deficiency.

Cheilitis. Dry, scaly, or fissured lips are another surface-level sign of iron depletion.

Angular Stomatitis, or cracking at the corners of the mouth. Same as above.

Metabolic Conditions

Hypothyroidism. Iron is involved in thyroid hormone metabolism, and iron-deficiency–related hypothyroidism can contribute to menstrual irregularities, including amenorrhea.

Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. Iron deficiency may impair insulin production and glucose utilization by limiting oxygen delivery to pancreatic and muscle cells. Chronic iron deficiency also increases fatigue and reduces physical activity, which further worsens blood sugar regulation.

Reduced Energy Metabolism. Iron deficiency leads to lower hemoglobin and reduced oxygen delivery to tissues. This outcome limits aerobic energy production (ATP generation), forcing the body to rely more on anaerobic metabolism, which is less efficient. The result is fatigue, poor endurance, and lower basal energy output, even at rest.

Weight Gain. While not a direct symptom, some individuals with iron deficiency may gain weight because of reduced physical activity, slower energy metabolism, and compensatory overeating of carbohydrates in response to fatigue or brain fog.

Cold Intolerance. Low iron (and other types of anemias) disrupts the body’s thermoregulation. People with a deficiency often feel cold even in warm environments.

Cardiovascular Conditions

Vascular Disorders. Iron deficiency impairs the cells that line the inside surface of blood and lymphatic vessels (endothelium). This condition reduces vessel flexibility, promotes vascular stiffness, worsens circulation, and increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Stroke. Stiff, fragile, or damaged blood vessels increase the risk of both ischemic stroke (caused by vessel blockage) and hemorrhagic stroke (caused by vessel rupture). Chronic iron deficiency contributes to cerebral hypoxia and further impairs neurovascular repair after stroke.

Heart Attacks. The same vascular damages that raise stroke risk also increase the likelihood of myocardial infarction. Continuous iron deficiency worsens oxygen delivery to cardiac tissue and may delay or impair recovery.

Heart Disease. Iron deficiency reduces oxygen delivery to the myocardium (heart muscle). This condition, in turn, contributes to fatigue, reduces exercise tolerance, and worsens heart failure symptoms.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest. Reduced hemoglobin lowers oxygen delivery and forces the heart to pump the blood harder to compensate. Over time, this persistent strain leads to ventricular hypertrophy, or the thickening of the heart's muscular walls. Just like any pumped-up muscle, an enlarged ventricle is more prone to spasm, which can interrupt the heart's rhythm and trigger cardiac arrest in people without a history of heart disease. The chance of restarting the heart is less than 25% even when it happens in a hospital setting with a cardiologist and defibrillator next to the victim.

Shortness of breath. With reduced hemoglobin, the blood carries less oxygen. To compensate, the body increases the respiratory rate during physical activity or exertion. This leads to the sensation of breathlessness, even during tasks that previously felt easy. In more advanced cases, it may occur at rest.

Tissue hypoxia. Low hemoglobin means less oxygen reaches the heart muscle itself. Over time, this can impair cardiac function and contribute to symptoms like chest pain, palpitations, or reduced exercise tolerance.

Gentiourinary conditions

Infertility in Women. Iron is required for ovulation, endometrial development, and early embryo implantation. Deficiency disrupts menstrual cycles, reduces ovarian reserve, and increases the risk of ovaries not releasing an egg (anovulation) or early miscarriage.

Infertility in Men. Iron plays a role in spermatogenesis and testosterone metabolism. Deficiency can impair sperm quality, reduce libido, and lower testosterone levels indirectly through chronic fatigue and systemic stress.

Increased Risk of Miscarriage. Adequate iron is necessary to support early placental development, oxygen delivery to the embryo, and immune tolerance during pregnancy. Low iron status can impair implantation, compromise fetal oxygenation, and increase susceptibility to infection, all of which may contribute to early pregnancy loss. Low folate or vitamin B-12 increases the risk further.

Amenorrhea (absence of menstruation). Iron deficiency can impair the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, especially when combined with low energy availability, chronic stress, or other nutrient deficiencies. These co-factors can suppress ovulation and halt the menstrual cycle.

Erectile Dysfunction (ED). Iron deficiency can contribute to ED through several overlapping mechanisms. Iron is required for nitric oxide signaling, which controls the dilation of penile blood vessels (FYI: Viagra and Cialis do the same). Deficiency may impair endothelial function and reduce blood flow. Indirectly, chronic iron deficiency causes fatigue, low mood, and reduced libido, all of which diminish sexual performance. The last factor applies to women's libido as much as to men's.

Developmental Conditions

Reduced or no Breast Milk. Iron is required for energy metabolism, hormone regulation, and tissue oxygenation, all critical factors for maintaining lactation. Severe deficiency can impair prolactin response, weaken maternal stamina, and reduce milk output over time. It may also coincide with other deficiencies (such as B vitamins or iodine) that further limit milk production.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Iron is required for brain development during and after pregnancy. Deficiency during this window can impair cognitive, sensory, and behavioral development. Several studies have found lower iron status in children with ASD and higher ASD risk in children born to mothers with iron deficiency during pregnancy, especially when combined with other risk factors like advanced maternal age and metabolic syndrome.

Impaired Cognitive Function. Low iron levels in infants, children, and adults can reduce attention span, memory performance, and learning ability.

Delayed Growth and Development. Chronic deficiency during childhood may impair height, weight gain, and neurodevelopment.

Behavioral Adaptations. Irritability, apathy, and reduced social engagement are often reported in children with iron deficiency.

I hate to sound like a used car salesman, but trust me, it wasn’t my goal to scare the bejuisus out of you with this long list of what can happen when you or your children are short on iron. The good news is, most of these conditions are preventable and reversible. But that starts with recognizing the risks first. I hope I’ve helped you to do that.

Normal Daily Losses of Iron

Iron is continuously lost from the body, but unlike most other nutrients, it is not actively excreted with urine, feces, or sweat. These ongoing losses must be replaced through diet, supplementation, or both to maintain adequate iron stores.

The following section outlines the typical daily losses of iron and the additional demands placed on the body during specific life stages:

The body loses approximately 1 to 2 mg of iron daily through sloughing of intestinal mucosa, skin desquamation (the shedding of dead cells from the skin’s top layer), and minor internal bleedings.

Women of reproductive age lose additional iron during menstruation, averaging about 1 mg per day but varying widely depending on the intensity.

Iron losses increase during pregnancy because the body's demand for iron rises sharply to support fetal development, placental growth, and expanded maternal blood volume. During pregnancy, an additional 800–1,200 mg of iron is needed to supply the fetus, form new red blood cells, and prepare for blood loss at delivery.

Lactation requires a continuous supply of iron for making breast milk required to support the infant’s growth. Approximately 0.3 to 0.5 mg is taken out per liter.

During infancy, childhood, and adolescence, iron losses may outpace dietary intake and cause deficiency. This demand is particularly high during growth spurts and puberty.

This section doesn’t include one-off situations such as acute bleeding during trauma, major surgery, or blood donation, all of which can result in sudden and significant iron loss. In these cases, iron is lost directly through blood loss rather than through gradual depletion.

While healthy individuals can typically recover from such events with time and supplements, repeated or poorly managed blood loss—such as frequent donations or surgical complications—can rapidly deplete iron stores and lead to deficiency if not corrected.

Risk Factors for Iron Deficiency

The following list ranks the most common causes of iron deficiency in order of relevance, starting with the most impactful factors. It focuses solely on factors that reduce iron intake, increase losses, or interfere with absorption, and gradually lower the body’s iron stores. This list does not cover the full range of causes behind anemia because iron deficiency is only one aspect behind it, and I'll touch on it further down.

Increased iron requirements during pregnancy, lactation, childhood growth, or intense physical activity. Iron demand rises sharply during these stages. Without increased intake, the body pulls from already limited stores until symptoms appear.

Chronic blood loss from menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding, parasitic infections, or heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia). Ongoing blood loss drains iron steadily. Many women with heavy periods or undiagnosed GI bleeding develop iron deficiency over time.

Inadequate dietary intake, particularly in vegetarian or vegan diets with low bioavailable iron. Plant-based diets lack heme iron and often rely on poorly absorbed non-heme sources. Even with good intentions, the math doesn’t add up.

Intestinal malabsorption from gastrointestinal disorders such as celiac disease, chronic enteritis, or inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamed or damaged intestines can't absorb iron well. In these conditions, even a perfect diet won’t make up the difference.

Bariatric surgeries and extended use of Ozempic-class appetite-suppressing drugs, resulting meager diet. Reduced appetite or stomach volume leads to chronically low intake of iron-rich foods. Deficiency is common and often underdiagnosed.

Extended weight loss diets and eating disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia. Restrictive eating nearly always reduces iron intake. In long-term cases, storage is depleted, and anemia follows.

Use of medications that impair iron absorption or increase blood loss, such as NSAIDs, antacids, PPIs, and H2 blockers. These drugs either irritate the intestinal lining, cause blood loss, or lower stomach acid, all of which reduce iron status over time.

Low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria) reduces iron solubility and absorption. Iron needs an acidic environment to stay soluble. Table salt deficiency, the only source of chloride in hydrochloric acid.

Frequent blood donations without a corresponding recovery diet and supplementation. Each donation removes 200 to 250 mg of iron. Without a plan to replace it, iron stores can drop sharply after just a few sessions.

Kashrut and halal-style diets. Religious slaughter laws require the complete draining of an animal's blood. Because a substantial portion of iron in meat is found in blood, this practice reduces the total iron content of the meat consumed under these dietary laws.

Poor quality and bioavailability of iron added to wheat and rice during fortification. Most iron fortification uses cheap, poorly absorbed forms. The label may say “iron,” but your body doesn’t get much from it.

Tea and coffee are consumed with meals, which inhibit iron absorption due to tannins and polyphenols. Polyphenols in these drinks bind non-heme iron in the gut. Drinking them with meals can cut iron absorption by half or more.

High-calcium meals or calcium supplements taken with iron-rich foods. Calcium competes with iron for absorption. A glass of milk or calcium pill at the wrong time can block uptake from an entire meal.

Athletes, especially endurance athletes, due to iron loss through sweat, GI microbleeding, and foot-strike hemolysis. Hard training increases losses and turnover. Endurance athletes often become iron-deficient despite good diets.

Chronic kidney disease impairs iron utilization and increases demand. Iron might be present, but it’s not used effectively. Kidney disease alters hormone signals needed to manage iron and red blood cells.

High fiber in supplements, laxatives, and fortified food binds minerals in the small intestine, including iron. It is also a source of considerable inflammation that further blocks iron absorption.

Poor quality of iron-containing supplements. Many over-the-counter iron products contain forms that are poorly absorbed or cause side effects. People stop taking them before they help.

Consuming tap, filtered, or distilled water and soft drinks. Treated tap or bottled water has little to no iron. Over time, this reduces background intake, especially in people who avoid iron-rich foods.

Non-stick cookware. Unlike traditional cast iron, non-stick pans don’t release trace iron into food. It’s a minor source, but in low-intake diets, every bit counts.

Alcoholism. Alcohol damages the gut lining and interferes with nutrient absorption. Chronic drinkers often develop multiple deficiencies, including iron.

Blood thinners. Anticoagulants, such as warfarin, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or aspirin, increase deficiency risk by causing gastrointestinal bleeding that may go unnoticed for quite some time. If you take these drugs and iron deficiency is detected, make sure your doctors investigate this possibility.

Stomach and intestinal ulcers and tumors (benign and cancerous) may shed small amounts of blood for quite some time without notice.

Gingivitis and other gum disorders can cause chronic low-grade blood loss through bleeding gums. This condition often goes unnoticed but may contribute to iron deficiency over time. Poor oral hygiene, microbial overgrowth, and deficiencies in vitamin C, vitamin K, and other micronutrients all play a role in gum inflammation and bleeding.

Now that you've learned the most common risk factors, identify the ones that apply to your situation and start unpeeling the ones you can. Each eliminated risk brings you closer to restoring iron balance and resolving the problems connected to it.

Cofactors Required for Assimilation of Iron

You may still have a full-blown iron-deficiency anemia with plentiful iron inside your body and in your diet because iron doesn’t assimilate and form hemoglobin without these cofactors:

Vitamin A is required to move iron out of storage sites in the liver, spleen, and bones. It supports red blood cell production and keeps the intestinal lining healthy for better absorption. Conversely, when vitamin A is deficient, iron can’t reach the bone marrow to synthesize hemoglobin.

Vitamin C improves iron absorption by converting ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to the more absorbable ferrous form (Fe²⁺) in the small intestine. It also forms soluble compounds with iron that stay available for uptake. When vitamin C is low, much of the iron from plant foods and supplements remains unabsorbed, especially in diets that contain absorption inhibitors like phytates or tannins.

Vitamin B-6 (pyridoxine) is involved in hemoglobin synthesis and the production of enzymes that regulate iron metabolism. It is also required for the formation of red blood cells in the bone marrow. When vitamin B-6 is deficient, the body may not be able to incorporate iron into hemoglobin efficiently, leading to a type of microcytic anemia that resembles iron deficiency but does not respond well to iron alone.

Folate (B-9) and vitamin B-12 are both required to produce red blood cells in the bone marrow. When either is deficient, red blood cell formation slows down and produces abnormally large, immature cells that can’t carry oxygen effectively. This anomaly leads to megaloblastic anemia, a condition that may occur alongside iron deficiency or mask its presence.

While we're on the subject, let’s not forget two other critical cofactors required to convert available iron into hemoglobin and to ensure there are enough red blood cells to use it effectively:

Amino Acids are the building blocks of blood cells, and enter the body exclusively through dietary proteins. High-quality sources include meat, poultry, fish, and seafood. Plant proteins are less complete and require careful dietary planning to provide all essential amino acids in adequate amounts. Any impairment of gastric digestion leads to incomplete protein breakdown, amino acid deficiency, and resulting blood disorders.

Essential Fatty Acids (EFAs), and especially omega-3s, are required for the structural integrity and flexibility of red blood cell membranes. Deficiency may reduce erythrocyte lifespan and impair their ability to pass through capillaries, contributing to anemia. Poor fat digestion or extremely low-fat diets can lead to EFA deficiency. Liquid Cod Liver oil is, by far, the best source of balanced EFAs.

Please keep all these co-dependencies in mind when confronted with chronic anemia and its own set of related problems.

Dietary Iron Toxicity

Taking iron supplements without the above supplements may restore ‘absolute deficiency,’ but will not resolve ‘functional deficiency.’ Not realizing this co-dependence, some people may double down on supplementation, and this may lead to iron toxicity.

Once absorbed, iron tends to accumulate in tissues such as the liver, heart, and pancreas, where it can cause damage. For this reason, public health guidelines prioritize avoiding overload rather than defining an optimal intake above the RDA. Clinical iron replenishment is done under supervision, based on lab values, not assumed needs.

Iron toxicity can occur in two primary forms—acute and chronic—depending on the dose and duration of exposure. Acute toxicity typically results from a large single intake, such as when a child accidentally ingests iron supplements. The earliest symptoms appear within the first six hours and may include nausea, vomiting (sometimes with blood), abdominal pain, diarrhea, and a metallic taste. As blood pressure drops and heart rate increases, signs of systemic distress can escalate quickly.

In some cases, there may be a temporary improvement in symptoms during a “latent phase” lasting up to 24 hours, which can delay diagnosis and treatment. A rebound of gastrointestinal symptoms and progressive deterioration often follows this. If not treated, severe cases may advance to metabolic acidosis, liver failure, bleeding disorders, seizures, coma, and even death.

Chronic iron toxicity develops over time due to excessive iron intake or accumulation. This can result from repeated high-dose supplementation, genetic conditions like hereditary hemochromatosis, or frequent blood transfusions used in the treatment of conditions such as sickle cell disease or thalassemia.

Hemochromatosis causes excessive iron absorption and accumulation in the body, even when dietary intake is normal. Over time, iron builds up in the liver, heart, and pancreas, leading to liver disease, diabetes, joint pain, fatigue, skin pigmentation changes, and in advanced cases, heart failure or cirrhosis. It is most common in people of Northern European descent and often goes undiagnosed until advanced organ damage.

Iron toxicity symptoms develop slowly and may include fatigue, joint pain, abdominal discomfort, elevated liver enzymes, and skin discoloration. In more advanced stages, iron may deposit in the pancreas, heart, or pituitary gland, leading to diabetes, cardiac arrhythmias, or hormonal imbalances.

Chronic iron overload is typically identified through persistently high levels of ferritin and transferrin during the blood test, often in the context of supplement use, blood transfusions, or a relevant family history. Without immediate intervention, iron toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage.

How to Find Out Absolute and Functional Iron Deficiency?

Iron deficiency can't be reliably diagnosed from a single test. You need a small panel of labs to assess storage, transport, and how well the body is using iron.

The most important marker is ferritin, which reflects how much iron is stored in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. A ferritin level below 30 ng/mL suggests depleted reserves, or absolute deficiency. And anything below 15 ng/mL confirms clinical deficiency. However, ferritin can also appear normal or elevated during inflammation, infection, or chronic illness. If there's a known inflammatory condition, ferritin alone isn’t enough.

The "Serum iron" test measures the iron circulating in the blood. It fluctuates with meals, time of day, and supplementation. It's unreliable on its own. A better measure is transferrin saturation (TSAT), or the percentage of transferrin binding sites that are actually carrying iron. TSAT below 20% is suggestive of deficiency; under 10–15% is typical in more advanced cases. Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) can also help. It tends to rise when iron is low, as the body produces more transferrin to scavenge what little iron is available.

A basic complete blood count (CBC) looks for low hemoglobin and hematocrit, reduced mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and elevated red cell distribution width (RDW). This combination points to microcytic and hypochromic anemias.

In clinics that use modern hematology analyzers, reticulocyte hemoglobin (CHr or Ret-He) is also useful because it drops early in deficiency, even before anemia shows up.

To sum it up: ferritin, TSAT, TIBC, and a full CBC are the core markers. They give a reliable picture of absolute and functional iron status when interpreted together. Single markers, especially ferritin alone, can mislead if you don’t know the full context.

You may wonder if a smartwatch or fingertip oximeter can detect iron deficiency through oxygen saturation. They can't. These devices measure how much oxygen is bound to hemoglobin but say nothing about how much hemoglobin is present or whether iron is available for oxygen transport. Blood tests remain the only reliable method to assess iron status.

Food Sources of Iron

As I noted earlier, iron in food comes in two forms: heme and non-heme. Heme iron is found only in animal tissue and is absorbed efficiently—typically between 15% and 35%.

Non-heme iron comes from plant-based foods and fortified products. It is absorbed less efficiently, usually in the 2% to 20% range, depending on other dietary factors.

The best sources of heme iron come from beef, lamb, liver, chicken thighs, turkey, and sardines. Organ meats like liver are especially rich, but they are no longer popular because of their strong taste, and are hated by children.

When I was little, my mother would make me a liver pate from pan-fried chicken livers, mushed together with sautéed onions, minced hard-boiled eggs, and lots of butter. In this form, the distinct liver taste was subdued, and I wouldn't cry or through tantrums when 'forced' to eat it smeared on the white bread. As I got older, I developed a taste for this dish, and it went especially well with a sour pickle and a shot of vodka.

Red meat remains the most reliable and bioavailable source of dietary iron for most people. I don't like the toughness of American beef, with the exception of Wagyu beef. Before COVID, we used to go to a fantastic burger joint called Zinburger. This smaller chain was very popular on the East Coast and in Arizona. Unfortunately, all of the East Coast locations were permanently closed during COVID.

We tried to make burgers from Wagyu beef at home, but they never tasted the same because restaurants use custom beef blends with high fat content and freshly ground meat. They cook on flat-top griddles that maintain consistently high heat across a wide surface for better browning and searing. Ventilation systems prevent steaming. Restaurant chefs also follow precise timing: patties are kept cold, seasoned just before cooking, flipped at the right moment, and rested before serving.

The same goes for steaks. Made at home, they rarely taste like the ones served in restaurants, and for the same reasons as above: better meat, higher heat, and precise control.

I could go on and on about this topic because I still remember the original method of wet aging. It was a distinct technique, where surface fermentation with bacteria and enzymatic breakdown softened the meat dramatically, giving it that tender, almost spreadable texture. It relied on controlled bacterial action, not dehydration or vacuum sealing.

The result was a velvety-soft steak that you could cut with a fork. This technique was common until the mid-1980s, when sanitary regulations forced it out of practice. What most people call 'wet aging' today bears little resemblance to that method, and most forms of 'dry aging' are more marketing than substance, except in the case of super-marbled Wagyu steaks from Japan, also known as Kobe beef. Their softness, however, comes from fat, not protein.

The last time we ate the steak like that was in 1996 at a three-star French restaurant in the Rockefeller Center in New York called La Reserve. Unfortunately, it was closed for good in 2000, shortly after the founder's retirement.

Non-heme iron is found in lentils, beans, tofu, pumpkin seeds, spinach, whole grains, and fortified cereals or flours. However, its absorption is highly variable and easily blocked by phytates (in grains and legumes), polyphenols (in tea, coffee, cocoa), and calcium.

Iron absorption is enhanced by vitamin C sources like oranges, grapefruits, tomatoes, bell peppers, or strawberries. Cooking in cast iron pans can also modestly increase the iron content of acidic or moist foods, especially when dietary intake is low.

People who rely solely on non-heme iron, like vegetarians, vegans, and pescaterians, require supplementation.

The Perils of Consuming Iron-Fortified Food

When World War II started, health screenings of military recruits in the US uncovered high rates of iron-deficiency anemia among men from poor backgrounds because their diets lacked good sources of iron and vitamins required for its assimilation.

In response, federal regulators introduced rules requiring iron, thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin to be added to refined wheat flour starting in 1941. Folic acid was added in 1998.

Their goal was to reduce the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia by increasing population-wide intake through the least expensive and most common bread, pasta, and breakfast cereals. Enrichment was applied to refined flour products because it was inexpensive to produce and easy to standardize.

This approach was based on the assumption that adding small amounts of iron to mass-market products would correct iron deficiencies without risk of harm. It also reflected the technological and economic limitations of the time.

Food-grade forms of iron had to be shelf-stable, non-reactive, and compatible with large-scale processing. This limited the options to a handful of synthetic and elemental compounds with low bioavailability but good manufacturing properties.

Iron fortification remains a core feature of current US nutrition policy and is still promoted as a low-cost intervention to reduce anemia, particularly in women of childbearing age and children.

Since then, this strategy has not been updated to reflect changes in dietary patterns, food technology, or current understanding of iron metabolism, overload risk, and intestinal damage.

When the US Food Pyramid was introduced in 1992 by the by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), bread, pasta, and cereals were placed at its base with a recommended 6 to 11 servings per day, not because of their nutritional value, but because they were fortified, heavily subsidized, and affordable for the poorest Americans.

This highly promoted policy contributed to widespread overconsumption of refined carbohydrates and has driven the epidemics of prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, and obesity that followed in the past three generations of Americans.

Lo and behold, at present (August of 2025), the number of overweight and obese Americans has reached 75%. It is the same number as the number of people with a genetic predisposition to gain weight. In other words, everyone who could gain weight is already overweight or obese.

Similar policies have been implemented in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, with small variations, and the rate of obesity and digestive disorders there is gradually approaching the United States' numbers.

Most of Western Europe, including Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries, does not require the iron fortification of flour or rice. Neither do Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand.

When Americans travel to most of Europe, they consume baguettes, pizza, pasta, and risotto with abandon, and come back home with less weight and zero digestive problems. The moment they touch the same food here, all of their problems with bloating, flatulence, diarrhea, indigestion, IBS, IBD, and demonized gluten sensitivity instantly come back.

What they don't know or realize – all of these problems have nothing to do with gluten, which is exactly the same in Italy, France, and Germany, but with iron and B-vitamins added to wheat flour and rice in the United States.

Rice fortification began in the 1950s as a targeted public health intervention. The initial US programs were led by the US Army and government nutrition agencies to address nutritional deficiencies among draftees consuming rice as a staple with few other dietary sources of iron or B vitamins.

The first large-scale rice fortification in the US used a process called coating or dusting, which added synthetic iron, thiamin, niacin, and riboflavin onto the surface of rice kernels. However, because rinsing and cooking removed most of the added supplements, later methods shifted to hot extrusion, producing fortified kernels that are blended back into ordinary rice, typically at a 1 to 100 fixed ratio.

Rice fortification was never adopted in the US on the same scale as wheat flour enrichment and is not mandatory nationwide. It remains a voluntary practice, largely limited to institutional food programs such as those serving the military, school lunches, or food aid shipments. Nonetheless, finding domestic non-fortified rice in the US is near impossible.

Outside the US, modern rice fortification efforts have expanded through global health initiatives in countries like India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and parts of Latin America, but most of these programs began in the 2000s.

Intestinal Disorders Related to Dietary Iron in Fortified Food

As I noted earlier, many Americans avoid wheat-containing bread, pasta, pizza, and cereals because they believe the problems they are experiencing are related to gluten, a plant protein in wheat. And while eating exactly the same food in Italy or France, which often contains even more gluten than American flour, they have zero issues.

Except for a small percent of people who are affected by celiac disease—about 1% of the population—all the rest are reacting not to gluten, but to added iron. Their reaction is linked to poorly tolerated forms of iron found in fortified foods and low-quality supplements, such as ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, ferrous gluconate, carbonyl iron, and elemental iron powders produced by electrolysis.

These forms of iron are used for fortification because they are inexpensive, shelf-stable, and do not affect the taste or appearance of food. However, they are poorly absorbed in the upper small intestine, so higher amounts are used to compensate.

As the unabsorbed iron transitions through the digestive tract, it triggers the following conditions in sensitive individuals:

Gastric irritation and acid reflux. Some of the above forms of iron are chemically reactive and can irritate the stomach lining when taken without food.

Nausea and vomiting. Unabsorbed iron can trigger the emetic reflex in sensitive individuals or at higher doses.

Abdominal pain and cramping. Free iron in the gut can stimulate smooth muscle contractions and cause discomfort.

Bloating and flatulence. Iron alters gut flora composition, increasing fermentation and gas production in the small and large intestines.

Loose stools and diarrhea. Iron that isn’t absorbed reaches the colon, where it disrupts microbial balance and irritates the mucosa, especially in people with preexisting gut inflammation.

Constipation. This effect is commonly attributed to ferrous sulfate and similar aggressive forms of iron, which are thought to slow colonic motility and harden stools. This reflects standard medical consensus, though the mechanism remains unclear and debatable. I believe this explanation is incorrect, but I’ve included it here because the association is widely reported.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Both diarrhea- and constipation-predominant subtypes can be triggered or worsened by chronic exposure to unabsorbed iron.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In genetically predisposed individuals, persistent iron-induced inflammation may contribute to or exacerbate Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Dysbiosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Iron is a growth factor for pathogenic bacteria, especially when delivered to areas of the gut where it doesn’t belong.

In short, iron fortification and low-quality iron supplements may be hidden contributors to the epidemic of digestive disorders that are blamed on gluten. If you disagree, remove all fortified wheat products for a few weeks and observe any changes. Or take a gastronomic tour of Italy. Bon voyage!

What Can You Do About This Mess?

Avoiding fortified foods in the United States requires deliberate effort. Most commercial breads, cereals, flours, rice, pasta, energy bars, and processed foods contain added iron and synthetic B-vitamins by default. These ingredients are listed on the label, but not always prominently. To reduce exposure:

If you can find them, buy breads and pasta made from whole grains that do not list iron, niacin, thiamin, riboflavin, or folic acid in the ingredients. In most cases, organic doesn't mean non-fortified.

Bake your own bread and pasta from non-fortified wheat flour. The King Arthur brand is widely available on Amazon and in supermarkets.

Buy rice labeled as non-enriched. These are often marked as organic or imported, especially from regions that do not practice fortification. You can find them at Korean, Chinese, and Japanese grocers. The only American brand that I know of is Lundberg Family Farms, but it's quite expensive and not widely available.

Washing or soaking fortified rice doesn't guarantee the removal of fortification kernels because they are intentionally made to look identical to regular rice and not to float to the surface.

Unlike white rice, brown rice in the USA isn't fortified because it retains its bran and germ layers, and they contain naturally occurring vitamins and minerals, so that you may use it as a substitute. But don’t count on its extra nutrients – after storage and cooking, they are practically non-existent.

Avoid cereals, instant breakfast shakes, and meal replacement products that rely on vitamin enrichment as a marketing feature.

People with underlying digestive issues, metabolic disorders, or inflammatory conditions are especially sensitive to synthetic iron in fortified food and its effects on the small and large intestines. In these cases, the elimination of daily exposure to fortified products may improve symptoms over time.

If you do eliminate all fortified food from your diet, you MUST take quality multivitamins and iron supplements when indicated. The US government wasn't stupid while implementing the fortification policy, and the intent was honorable, but the way it was implemented was close to genocidal, and is the primary driver of spending over $4.5 trillion on healthcare.

Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) for Iron

(per day, in milligrams)

| Age Group | Males | Females |

| Infants | ||

| 0–6 months (AI)* | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| 7–12 months | 11 | 11 |

| Children | ||

| 1–3 years | 7 | 7 |

| 4–8 years | 10 | 10 |

| 9–13 years | 8 | 8 |

| Adolescents | ||

| 14–18 years | 11 | 15 |

| Adults | ||

| 19–50 years | 8 | 18 |

| 51+ years | 8 | 8 |

| Pregnancy and Lactation | ||

| Pregnant (14–50 years) | – | 27 |

| Lactating (14–18 years) | – | 10 |

| Lactating (19–50 years) | – | 9 |

For this reason, iron supplements are sold in containers with child-resistant caps, and dosages are limited to RDA values to minimize the risk of accidental overdose.

These recommendations are meant to prevent deficiency, not to optimize health, energy, or performance. They do not account for factors like chronic inflammation, poor absorption, drug-nutrient interactions, or individual variation in metabolism.

There is no ODA (Optimal Daily Allowance) for iron because excess iron is considered toxic, even in relatively small amounts. Unlike water-soluble vitamins, excess iron is not easily excreted from the body. The body has no regulated mechanism for eliminating iron except through blood loss.

How to Eliminate Iron-Related Deficiencies and Reverse Anemia

If, after reading this article, you suspect having absolute or functional iron-deficiency, related anemias, and digestive disorders, I recommend taking the following steps:

-

If you recognize one or more symptoms of iron deficiency or anemia described on this page, start taking our Conezymated Once Daily Multi (or a similar formula) along with Conezymated Vitamin B-12 (or similar) right away. This approach helps your body immediately make better use of the iron already present in your diet and tissues.

If you’re a woman with an active menstrual cycle, you can start taking our Easy Iron formula in addition to the above supplements right away to help compensate for the iron lost during menstruation. It contains a safe, dietary-level dose of iron consistent with public health guidelines and is unlikely to cause overdose. The same recommendation applies if you’re planning a pregnancy, currently pregnant, breastfeeding, or recovering postpartum.

If you already have a confirmed case of iron deficiency or iron-related anemia, you can begin taking all three supplements (Multi, B-12, and Iron) right away.

-

If you are a healthy man or a postmenopausal woman, ask your doctor to run a full iron panel to determine whether you need iron supplementation.

The recommended criteria are described in the How to Confirm Absolute and Functional Iron Deficiency section. For specificity, request “iron studies with ferritin, transferrin saturation, soluble transferrin receptor, and CRP.”

CRP (C-reactive protein) is an inflammation marker. Ferritin, which reflects stored iron, also rises during inflammation. Knowing both helps distinguish between absolute and functional iron deficiency. When iron stores are low, ferritin levels can still appear normal or elevated if inflammation is present, masking true deficiency.

When CRP is elevated and ferritin is high or normal, but transferrin saturation is low, functional iron deficiency is more likely. For this reason, including CRP improves the accuracy of interpreting iron studies, especially in the context of chronic illness, infection, or autoimmune disease. Ask your doctor to explain the results in context and guide your next steps.

If the results point to absolute iron deficiency, try to eliminate as many causes of iron deficiency as I outlined in the Risk Factors for Iron Deficiency section above, and start taking all three supplements (Multi, B-23, Iron) recommended above.

If the results point to functional deficiency, I recommend taking the Conezymated Once Daily Multi formula and Conenzymated Vitamin B-12 to improve existing iron utilization for reasons described in the Cofactors Required for Assimilation of Iron section.

In case you have any of the digestive conditions described in the Intestinal Disorders related to Dietary Iron, eliminate all of the fortified food mentioned there, and replace it with non-fortified versions.

In case you have an absolute and functional deficiency, start with point #5 above to resolve digestive disorders, then proceed with #4 (testing), and a few weeks later, with #6 (supplementation).

Repeat the iron panel 8 to 12 weeks after starting this plan. This timeframe allows iron levels to stabilize, red blood cells to regenerate, and digestive symptoms to improve. Choose the earlier end (8 weeks) for more severe deficiencies, or the later (12 weeks) for milder cases.

In this protocol, iron is provided only through well-absorbed supplements within the safe daily intake range, alongside multivitamins and a non-fortified diet. There is no risk of iron overload from excessive dosing, but testing at 8 weeks will help confirm that iron absorption and utilization are improving, that no ongoing losses are present, and that the selected supplement strategy is effective.

If iron markers remain unchanged or worsen, this early check allows time to investigate other causes before the deficiency becomes more advanced. If there are no improvements, seek advice from your doctor.

Avoid bread, pasta, and cereals made with fortified wheat flour. Once you have identified iron-related issues and made the effort to correct them, fortified products can undo your progress. Avoiding them is the most reliable way to keep steady iron levels, prevent recurrence of symptoms, and avoid inflammation and digestive complications, particularly if you are extra sensitive. And if not, no harm is made, except, maybe, some flatulence from extra bacterial growth and fermentation.

Take a high-quality iron and multivitamin supplement from our store or similar to prevent absolute and functional iron deficiencies.

Take an iron supplement, multivitamins, and vitamin B-12 together with the first meal of the day, and calcium-containing supplements in the evening (if you take one).

These simple and inexpensive steps will have a profound effect on your health, quality of life, and longevity. And your family, too!

Takeaways

As you could see from the length of this page, the subject of iron deficiency and related anemias is vast, but the most important concepts are straightforward. The following takeaways distill the key points from this article into a compact summary you can refer back to or share with others:

Iron deficiency and anemia are not the same. You can have normal hemoglobin and still be iron-deficient if your body can't access or use stored iron.

Over 50% of American women aged 18–50 are either absolutely or functionally iron-deficient, and most have no idea.

Functional iron deficiency is just as dangerous as absolute deficiency—and far more likely to be missed by standard blood tests.

Iron deficiency can cause or aggravate dozens of chronic conditions, including fatigue, depression, infertility, hair loss, and even heart failure.

You can eat a perfect diet and still end up iron-deficient if your digestion is impaired or essential cofactors like vitamin A, B-6, B-12, folate, and EFAs are missing.

The iron added to fortified bread, pasta, rice, and cereal in the U.S. is cheap, poorly absorbed, and a major contributor to digestive problems blamed on gluten.

Kosher and halal meat contain far less heme iron than conventional meat because of complete blood drainage. That wasn't a problem centuries ago, but it is now.

Most over-the-counter iron supplements use aggressive salts that cause constipation, bloating, or stomach pain. If your supplement gives you side effects, it's the wrong one.

Cast iron cookware no longer contributes meaningful dietary iron because it's rarely used and poorly maintained.

Taking iron without fixing digestion or restoring cofactors leads to functional deficiency—even when blood iron looks normal on paper.

Iron toxicity is real. That's why iron is not included in our Once Daily Multi and should only be taken when deficiency is confirmed or strongly suspected.

The fastest way to eliminate iron deficiency is through targeted supplementation, high-quality multivitamins, and elimination of all fortified foods that damage your gut.

If these points match your symptoms, test results, or lived experience, don't wait for them to get worse. Iron deficiency is preventable, measurable, and fixable once you know what to look for and what to avoid.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. Can I have normal hemoglobin but still be iron deficient?+

Yes, you can. This condition is called functional iron deficiency. Your ferritin, the storage form of iron, might look fine on paper, but your red blood cells still can’t access it. In other words, iron is present but not usable. This situation is more common than most doctors realize, and it fools even seasoned clinicians into dismissing fatigue and other symptoms as “normal.”

I explain this issue in the section on absolute vs. functional iron deficiency. The latter often accompanies chronic inflammation, infection, autoimmune conditions, or digestive disorders that interfere with cofactors like vitamin A, B-6, B-12, folate, or amino acids.

You may have plenty of iron in storage as ferritin, but without these supporting elements, it doesn’t convert to hemoglobin. I am being repetitive here to drive this point through and highlight this 'paradox' again and again.

Q. What blood tests should I ask for to check iron status?+

I covered this in the section How to Confirm Absolute and Functional Iron Deficiency. Ask for ferritin, TSAT, TIBC, and CBC. If there’s any inflammation, also request CRP to help interpret ferritin accurately. For a deeper look, include reticulocyte hemoglobin (CHr or Ret-He), if your lab offers it.

Q. Why am I still tired after taking iron supplements?+

Iron alone can't fix anemia unless all of the other required cofactors are in place. You also need vitamin A to release stored iron, vitamin C to reduce and absorb it, B-6 and amino acids to make hemoglobin, and EFAs to maintain red blood cell membranes.

If any of those are missing or blocked by poor digestion, iron won’t help much. I emphasized these points in the Cofactors Required for Assimilation of Iron section.

The other reason – most consumer-grade supplements use low-grade iron forms. It’s also why I recommend combining a quality iron supplement with a professional-grade multivitamin.

There are many other conditions behind chronic fatigue described on this page and the rest of the site. Please study them thoroughly to connect the dots.

Q. How long does it take to correct an iron deficiency?+

On average, from 8 to 12 weeks. That’s the amount of time it takes for red blood cells to regenerate and for lab values to reflect improvement. Severe cases may need more time. But if you don’t feel better within that timeframe, something is blocking absorption or interfering with iron utilization (i.e., converting it to hemoglobin).

If lab results don’t improve, revisit digestion, inflammation, or the quality of your supplement. I provide specific recommendations in the How to Eliminate Iron-Related Deficiencies and Reverse Anemia section.

Q. Why does iron upset my stomach?+

Because most supplements use forms like ferrous sulfate or fumarate, which are chemically harsh and poorly absorbed, the leftover iron stays in your gut, oxidizing and irritating the lining. That’s why you get nausea, bloating, diarrhea, or constipation.

I covered this topic in the section on Dietary Iron Toxicity and The Perils of Consuming Iron-Fortified Food. If your small intestine is already inflamed, low-quality iron makes it worse. That’s why I recommend taking professional-grade, highly absorbable forms, and always with the right cofactors.

Q. Can I fix iron deficiency with diet alone?+

In theory, yes. In practice, not likely. Most people don’t eat enough red or organ meats, and even when they do, digestive damage or cofactor deficiencies block absorption. Plant-based diets don’t provide heme iron, and fortified foods make things even worse.

In the Where Does the Iron Come From and The Perils of Consuming Iron-Fortified Foodsections, I explain why American wheat and rice products are an iron deficiency trap, not a solution. Unless you address both diet and digestion, you’re unlikely to correct iron deficiency without quality supplements.

Q. Why am I iron-deficient if I eat meat?+

Because eating meat is not the same as absorbing or utilizing its iron, low stomach acid, gut inflammation, low vitamin A, B-6, B-12, and folate, and even poor chewing habits can all interfere. So can tea, coffee, or calcium-rich foods that are taken at the same time.

Check the Cofactors Required for Assimilation of Iron and Risk Factors for Iron Deficiency sections for more information. Eating the right foods is only one step.

Q. Is iron deficiency common after weight loss surgery?+

Very. Bariatric procedures reduce stomach volume and acid production, both of which are essential for iron absorption. If you eat less, absorb less, and don’t supplement, iron deficiency is almost guaranteed.

This outcome and similar others are mentioned under Risk Factors for Iron Deficiency. It also applies to people on Ozempic-class drugs with similar effects: suppressed appetite, reduced intake, and blocked absorption.

Q. Can men have iron deficiency?+

Yes, and more often than most people think. The prevalence is lower than in women, but it still affects 16% of men aged 18–50, and about the same after age 65. If you lose blood (from ulcers, medications, or gum disease), have poor digestion, or donate blood often, you're at risk.

I provided full stats in the section How Common is It? The notion that men are “immune” to iron deficiency is a dangerous myth, especially when heart disease, fatigue, and cognitive issues are involved.

Q. Is low ferritin dangerous even with normal hemoglobin?+

Yes. Ferritin reflects stored iron, and when it drops, you’re running on fumes. Even if your hemoglobin looks okay, oxygen delivery is already compromised, and symptoms like fatigue, hair loss, or shortness of breath may show up.

I explain this contradiction in Cofactors Required for Assimilation of Iron and throughout the Iron-Deficiency Disorders section. Waiting for hemoglobin to drop before taking action is like waiting for your gas tank to hit zero in the middle of a desert. By the time you see it on the dashboard, it’s already too late.

Q. You mentioned that kashrut and halal diets cause iron-deficiency anemia. Do you have proof, and why wasn't it an issue for Jews and Muslims who invented this practice?+

Yes, there’s a physiological basis. When blood is fully drained from meat, as is required in kashrut and halal preparation, nearly all of the heme iron goes out with it. Since heme iron is the most absorbable form, removing it dramatically reduces the meat’s nutritional value. If this is your primary protein source, and you don’t supplement, you risk deficiency over time. This isn’t speculation, but a consequence of basic hematology and digestive physiology.