The Warning Signs of Latent Constipation

Of everything I’ve written over the past 25 years, the information on this page may be the most consequential for your health, quality of life, and longevity because all colorectal disorders described here start taking root in your early teens, turn into a nuisance between your twenties and forties, and become a wrecking ball past your fifty. The earlier you catch them, the longer you get to enjoy a life free of constant pain and worth living.

Merriam-Webster defines the word ‘latent’ as “present and capable of emerging or developing but not now visible, obvious, active, or symptomatic.” In other words, latent is something you already have but have not yet noticed, a landmine with a time delay fuse.

This article describes 23 colorectal disorders that are the obvious and active symptoms of otherwise invisible latent constipation. I first described this condition back in 2005 in Fiber Menace.

If left unaddressed, latent constipation eventually becomes oh-so-visible and irreversible. Recognizing it early let you prevent future colorectal disorders well before they, quite literally, bite you in the ass.

These disorders range from the ubiquitous hemorrhoids and diverticular disease all the way to colorectal cancer. How big are the risks?

Well, in the United States alone, between 300,000 to 500,000 colectomies are performed each year. This procedure involves partial or complete removal of the colon and is done for several key reasons:

Colorectal cancer accounts for an estimated 120,000 to 140,000 colectomies annually, representing about 40% of total cases.

Diverticulitis is behind 100,000 to 150,000 colectomies, primarily for recurrent or complicated cases.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, results in 50,000 to 70,000 colectomies per year.

Other conditions, such as ischemia (necrosis related to reduced blood flow), volvulus (the part of the colon loops around and folds over itself), or trauma, contribute an additional 30,000 to 50,000 procedures.

And it ain't gonna get better any time soon. The global colostomy bags market was valued at approximately $2.56 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow by $4.24 billion by 2032.

The Genesis of the Problem

The problem starts with the doctor’s attitude about constipation. This is an excerpt from the Constipation section of the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, Professional Edition:

“In Western society, normal stool frequency ranges from 2 to 3/day to 2 to 3/week.” [link]

The Merck Manual is a default go-to reference for practically all Western medical doctors. That’s the source doctors and insurance companies refer to when diagnosing clinical disorders.

This statement literally means that if you come to see your doctor, and they’ll ask you how often you move your bowels, and you reply: “Two to three times a week,” or at least once every three and a half days, from their perspective, YOU ARE REGULAR.

If you still insist on a solution regardless of your frequency, a doctor may prescribe you a laxative, and you start moving your bowels daily. So, technically speaking, YOU ARE REGULAR. In reality, you are using artificial means to stimulate regular bowel movements, but the problem is still there, and that is what I mean by LATENT CONSTIPATION.

If I were writing The Merck Manual (fat chance), my definition of constipation would be:

“The lack of effortless, unnoticeable, and near instant bowel movement after each major meal or, at the very least, once daily, is a sign of latent constipation and the early predictor of a future irreversible disorders, such as enlarged hemorrhoids, diverticular disease, distended colon, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel diease (IBD), and colorectal cancers.”

The opposite of the 'effortless, unnoticeable, and near instant bowel movement' are straining, discomfort, pain, and incomplete emptying along with any of the 23 conditions described below:

[Abdominal Bloating] [Flatulence] [Abdominal Pain with Bloating and Gas] [Straining During Defecation] [Pain During Defecation] [Large or Hard Stool] [Fecal Impaction] [Decreased Urgency or Rectal Sensitivity] [Dependence on Laxatives] [Dependence on Laxogenic Foods] [Dependence on Dietary Fiber] [Absence of Strong Post-Meal Urge] [Hemorrhoidal Disease] [Anal Fissure] [Rectal Prolapse] [Intermittent Diarrhea] [Diverticular Disease] [Redundant Colon] [Colon Distention] [Megacolon] [Non‑Genetic Polyp Formation] [Appendectomy in Adults] [SIBO]

1. Abdominal Bloating

Chronic abdominal bloating adds inches to people’s waistlines, making normal-weight men and women appear overweight and already overweight — appear obese. I see it daily during park walks, at the beach, and in the gym. Most assume it’s visceral fat, but in many cases, it isn’t.

Reducing abdominal bloating will change your appearance faster than Ozempic, with no fat loss involved, and the difference becomes visible within days or weeks, not months.

Other than pregnancy, abdominal wall laxity after delivery, and ascites (the abnormal build-up of fluid in the abdomen related to liver cirrhosis or cancer), there are three primary mechanical causes of bloating in otherwise normal-weight people: (1) a distended stomach from overeating, (2) distended small intestine from trapped gasses, and (3) distended large intestine from large stools. Flatulence doesn't affect the large intestine as much because gases have an outlet for exit.

Each of these three conditions is an early warning sign of current or future problems that can be easily addressed and reversed through diet and lifestyle changes.

Wearing compression clothing can worsen many of these problems by redirecting pressure inward instead of outward, affecting the uterus, liver, spleen, kidneys, bladder, diaphragm, and, indirectly, the lungs and heart.

So, if your three-year-old starts asking, “Mommy, is Daddy having a baby?” — it ain’t funny.

Primary Symptoms

Persistent or intermittent fullness, pressure, or visible distension in the abdomen, often intensifying after meals or as the day progresses. Patients may also experience sharp pain when pressing (palpation) on the abdominal wall beneath the diaphragm (subdiaphragmatic margin )and along the right and left flanks (lateral abdominal regions).

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from stool retention in the colon, slowed transit, and gas accumulation from bacterial fermentation. In latent constipation, weakened motility allows gas and residual stool to linger, increasing intraluminal volume and pressure.

Prevalence

A global online survey across of 51,425 adults found that approximately 18% experience bloating at least once weekly [doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.05.049]. I believe this number is underreported.

Bloating is common even in those who report daily bowel movements and correlates strongly with conditions like IBS, enterities, and delayed stomach emptying.

Related Conditions

Flatulence, abdominal pain, SIBO, diverticular disease, IBS‑C, loss of urge after meals, nausea and vomitting, cramping during the period.

Diagnostic Implications

Often dismissed as “gas,” “diet,” or IBS. In cases of latent constipation, it indicates incomplete evacuation or delayed transit, even when frequency appears normal.

Reversibility

Early-stage bloating typically reverses with a reduction in stool volume, improved motility, and addressing underlying latent constipation.

2. Flatulence

Flatulence by itself isn't a pathology. A healthy person's colon will produce about 0.5 to 1.5 liters of gas daily, primarily from bacterial fermentation of insoluble and soluble fiber and mucus, and will pass the gas 10 to 20 times per day.

Some of the gas may reflux back into the small intestine through the ileocecal sphincter and be absorbed into the blood from there. It's what happens when gas is retained for prolonged periods, such as when you are not alone and hold in the gas for obvious reasons.

I need to mention that no gas is also a problem because it means the absence of gas-producing bacteria in the colon. These bacteria play a key role in immune regulation and support the production of certain vitamins, including vitamin K and some B-complex vitamins.

The gas, however, turns into a social and medical problem when too much of it results in bloating, cramping, and excessive flatulence. Almost invariably, it is a sign of underlying colorectal disorders and latent constipation.

So yes, when it comes to gas, it’s a classic case of damned if you have it, damned if you don’t.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from prolonged fermentation of residual stool and undigested food in both the colon and the distal small intestine. In latent constipation, delayed transit allows gas-producing bacteria extended access to substrates, often exceeding normal clearance and increasing discomfort.

Prevalence

Healthy adults typically pass gas between 8 and 20 times per day. Problematic flatulence affects 10–20% of the general population, especially among those with slowed transit or dietary excess of fermentable substrates (Stanghellini et al., 2024). Among patients with constipation-predominant IBS, a group frequently affected by latent constipation, over 70% report excessive flatulence as a disruptive symptom (Ghoshal et al., 2022).

Related Conditions

Bloating, abdominal pain with gas, straining, IBS‑C, SIBO, intermittent diarrhea, reduced urge after meals.

Diagnostic Implications

Flatulence is frequently attributed to diet or lifestyle. In latent constipation, however, persistent or excessive gas reflects slowed colonic transit and incomplete stool evacuation, especially when other symptoms are present.

Reversibility

Typically reversible with normalization of bowel transit and effective treatment of latent constipation.

3. Abdominal Pain with Bloating and Gas

This particular trio of gut troubles may seem redundant with the first two, but it actually isn't, because, as I explained earlier, bloating by itself, especially in skinny people, is a functional state related to the temporary distention of the stomach from too much food and fluids, gases naturally formed inside the small intestine during digestion, and gases from fermentation in the large intestine from consuming too much fiber.

If you are healthy, these three problems are transient and will go away as soon as the last meal gets digested, excess fiber is fully fermented, and excessive gas leaves your body with flatulence, a lady-term for farts.

When the pain, particularly near-constant, is introduced, that is a strong indication of some of the following conditions:

Gastric ulcer. Pain is typically in the upper central abdomen (epigastrium), described as burning or gnawing. It often occurs shortly after eating and may improve with antacids or worsen at night. Mild cases are frequently mistaken for heartburn or simple indigestion.

Duodenal ulcer. Usually presents with similar burning pain as gastric ulcers but tends to occur 2–3 hours after meals or during fasting (e.g., early morning). Pain may improve with food. Localized to the upper abdomen, but exact location may not be distinct from gastric ulcers.

Gallbladder disease. Right upper quadrant pain, sometimes radiating to the right shoulder or back. May be sharp or cramping, especially after fatty meals. However, vague or mild gallbladder discomfort is often misinterpreted as bloating or gas.

Acute enteritis. Characterized by diffuse or periumbilical pain with cramping. Pain is often accompanied by diarrhea, nausea, or fever, but mild cases may lack these. Can result from viral, bacterial, or foodborne infections. Frequently confused with IBS or dyspepsia.

Fecal compaction or impaction. Dull, persistent pain in the lower abdomen, more commonly left-sided. May be accompanied by bloating, a sense of incomplete evacuation, or paradoxical diarrhea. Often underdiagnosed without a rectal exam or imaging.

Pancreatitis (mild or early). Pain starts in the upper abdomen and can radiate to the back. Typically steady and deep. Often overlooked unless severe or confirmed with labs (lipase, amylase). Alcohol and gallstones are leading triggers.

SIBO. Pain is diffuse, crampy, and often described as bloating or gas-related pressure. Symptoms fluctuate and are strongly food-related. Commonly mistaken for food intolerances, mild IBS, or "nervous stomach."

Gynecologic causes (e.g., endometriosis, cysts, adhesions). Pain is lower abdominal or pelvic, varying with the menstrual cycle. Can mimic colonic or bladder pain. Often missed or misdiagnosed as GI or urinary issues.

This list is far from complete. The abdominal region is so tightly packed with organs that the pain could just as easily stem from the spleen, kidneys, liver, bladder, muscles between the ribs, or even the heart and lungs. In nearly all cases, retained gas becomes an exacerbating factor, and visible bloating is a common symptom, often dismissed but rarely meaningless.

Be extra careful around young doctors who have never missed a meal, never held in gas on a date, and think bloating is just something 'old cranks' exaggerate on TikTok. If they suggest it's all in your head, tell them your head doesn't fit in your abdomen, and find yourself a gray-haired, 'old-fart' physician with their brain in the right place.

Speaking of young doctors... When it comes to vague complaints like the ones above, a few 'bad apples' can be particularly hazardous to your health because they may lack empathy, listening skills, and lived experiences to diagnose non-specific internal conditions correctly. If you sense even the slightest whiff of arrogance, ego, or contempt, run for your life.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from prolonged stool retention and fermentation in the colon and distal small intestine. Latent constipation impedes normal transit, causing gas accumulation and mechanical distension that activate visceral nociceptors, leading to pain.

Prevalence

A global Rome Foundation-led survey of 51,425 adults across 26 countries found that 61.7% of respondents reporting weekly abdominal pain also experienced bloating at least once per week, with 18% of the general population reporting weekly bloating overall (emedicine.medscape.com, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Related Conditions

Bloating, flatulence, straining, IBS‑C, SIBO, intermittent diarrhea, reduced post-meal urge.

Diagnostic Implications

These symptoms are often labeled as IBS or functional dyspepsia. In latent constipation, they signal delayed transit, residual stool fermentation, and progressive colon dysfunction—even in the absence of overt constipation.

Reversibility

Reversible when stool transit is restored and latent constipation is treated.

4. Straining During Defecation

Primary Symptoms

Effortful or forceful exertion to pass stool, often described as pushing or bearing down for extended periods. Patients may use abdominal or perineal pressure and still feel that evacuation was incomplete.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from impaired colonic propulsion and enlarged, hard stool mass. In latent constipation, compensatory mechanisms—like straining—mask slow transit and reduced reflex action, maintaining stool frequency but perpetuating dysfunction.

Prevalence

In general adult populations, 17–23% report straining during at least 25% of bowel movements without meeting clinical constipation criteria (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, aafp.org). For patients with functional constipation or IBS‑C, the Rome IV criteria note straining in more than 25% of defecation episodes as a defining symptom (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Related Conditions

Feeling of incomplete evacuation, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, rectal prolapse, diverticular disease, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, reduced rectal sensitivity, loss of post-meal urge.

Diagnostic Implications

Straining is frequently perceived as benign or lifestyle-related. In latent constipation, it signals compensatory behavior needed to overcome weakened colonic motility and large stool bulk. Frequent straining indicates progression towards organic changes.

Reversibility

Early-stage straining often resolves after normalizing stool consistency and transit through diet modification, improving motility, and breaking the cycle of forced evacuation.

5. Pain During Defecation

Primary Symptoms

Sharp, burning, or tearing sensation in the anus or rectum during bowel movements, often described as severe or stinging pain. Patients commonly report associating the pain with passing firm or hard stool.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from mechanical trauma to anorectal mucosa, including hemorrhoids, fissures, or anal stretching by hard stool. In latent constipation, insufficient colonic motility leads to the formation of denser stool masses that damage sensitive tissues during defecation.

Prevalence

Anal pain during bowel movements is reported by up to 30 percent of patients with chronic constipation and is included in practice guidelines as a key symptom for diagnosis (Sitzler et al., 2021; MCG Clinical Pathways, 2020). Among patients with functional constipation meeting Rome IV criteria, anorectal pain is reported about 25–35 percent of the time.

Related Conditions

Hemorrhoids, anal fissures, straining, rectal prolapse, feeling of incomplete evacuation, SIBO.

Diagnostic Implications

Often dismissed as hemorrhoids or stress-related. In latent constipation, recurring pain during defecation signals persistent stool hardness and unnoticed colon dysfunction, even if frequency remains in the daily range.

Reversibility

Pain usually resolves once stool consistency is corrected, motility improves, and latent constipation is addressed. Early intervention prevents development of chronic fissures or anal pathology.

6. Large or Hard Stool (BSF Types 1–3)

Primary Symptoms

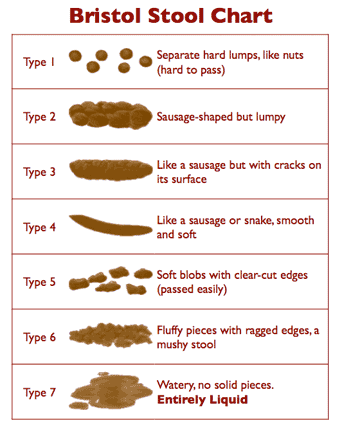

Stools that are hard, lumpy, flat, or sausage-shaped with cracks (Bristol Stool Form Scale Types 1–3), even when passed regularly. They require noticeable effort to expel.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from slowed colonic transit and elevated water absorption. In latent constipation, stool remains in the colon longer than normal, becoming compacted, dry, and bulky, leading to BSF Type 1–3 stools that are mechanically difficult to pass.

Prevalence

A large cross-sectional study in India found that, among individuals reporting daily bowel movements, 20.5 percent regularly experienced BSF Types 1 or 2; Types 3 and 4 were most common overall (35.6 percent and 32.5 percent, respectively) (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). A U.S.-based survey reported hard stools in 19.3 percent of participants.

Related Conditions

Straining, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, rectal prolapse, colonic redundancy, SIBO.

Diagnostic Implications

Often overlooked if frequency remains daily. BSF Types 1–3 indicate stool characteristics consistent with latent constipation and should prompt evaluation of transit and evacuation efficiency.

Reversibility

Improves when transit time and hydration are normalized. Persistent hard stools in regular defecators suggest ongoing colonic dysfunction.

7. Fecal Impaction

Primary Symptoms

A hard mass detectable by abdominal or rectal examination in the ascending colon or right lower abdomen, even when bowel movements are regular.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from slow colonic transit and localized stool retention. In latent constipation, stool can become compacted and remain in the ascending colon, leading to partial impaction that becomes palpable during physical examination.

Prevalence

Fecal impaction occurs in up to 42% of geriatric inpatients and is commonly detected as a palpable mass in the descending or sigmoid colon. Although studies in the general ambulatory population are limited, clinical guidance notes that palpable stool in any location is a strong indicator of stool burden and reduced motility (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The Medscape review on constipation also notes that patients with slow transit may demonstrate palpable stool in the sigmoid or descending colon.

Related Conditions

Large or hard stools, straining, intermittent diarrhea (overflow), SIBO, colonic distention, diverticular disease

Diagnostic Implications

A palpable abdominal mass suggests a significant stool burden and should prompt evaluation of transit time even when patients report daily bowel movements. It is a clinical sign often overlooked in routine exams.

Reversibility

Strongly reversible with appropriate disimpaction, normalization of motility, and treatment of underlying latent constipation.

8. Decreased Urgency or Rectal Sensitivity (rectal hyposensitivity)

Primary Symptoms

Reduced sensation of rectal fullness or urge to defecate, often unnoticed until bowel movements occur at scheduled times or under pressure.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from repeated foam-like retention and distention of stool leading to desensitization of rectal afferent pathways. In latent constipation, prolonged overstretching blunts the reflex loop that signals the need to defecate, weakening the normal urge response.

Prevalence

Studies using anorectal manometry and sensory testing report rectal hyposensitivity in 15–25% of patients with chronic constipation and defecatory disorders. One study involving 1,351 patients showed 16% overall prevalence, ranging from 23% in those with constipation to 33% in obstructed defecation cases (gutnliver.org, researchgate.net, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Another review found up to 25% rectal hyposensitivity among adult cases of chronic constipation. Abnormal urge perception—often a proxy for reduced rectal sensitivity—occurs in about 50% of women with chronic constipation (researchgate.net).

Related Conditions

Straining, incomplete evacuation, SIBO, dependence on laxatives or fiber, rectal prolapse.

Diagnostic Implications

Decreased urge is often overlooked when stool frequency remains “normal,” but effort is high. In latent constipation, it signals neural adaptation and progressive anorectal dysfunction that increases the risk of worsening motility impairment.

Reversibility

Partial recovery is possible with behavioral retraining, biofeedback, and restoration of normal rectal tone. Advanced desensitization is less responsive but can still improve with prolonged intervention.

9. Dependence on Laxatives

Primary Symptoms

Habitual need to take laxatives—stimulant, osmotic, or bulk-forming—to produce a bowel movement. Patients may believe they can only go when using these products.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from chronic reliance on agents that override weakened colonic motility. Latent constipation diminishes intrinsic propulsive force, creating a feedback loop where the bowel becomes conditioned to external stimulation rather than natural reflexes.

Prevalence

Among adults in the general population, regular laxative use ranges from 1 percent to 18 percent, depending on age and definition. Among individuals with chronic or episodic constipation, use increases to between 3 percent and 59 percent (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). In hospitalized elderly patients, 29 percent had been prescribed laxatives at admission, rising to 60 percent during their stay, often without documented constipation (bmcgastroenterol.biomedcentral.com).

Related Conditions

Dependence on laxogenic foods, dependence on dietary fiber, straining, reduced urge after meals, loss of colonic tone, SIBO, hemorrhoids.

Diagnostic Implications

Chronic laxative use is frequently considered benign self-care. In the context of latent constipation, it often signals loss of colonic autonomy and progression toward organic dysfunction.

Reversibility

Partial in early stages. Discontinuation of stimulant laxatives helps restore motility, especially when combined with bowel retraining and treatment of underlying latent constipation.

10. Dependence on Laxogenic Foods

Primary Symptoms

Habitual reliance on foods with laxative properties (e.g., prunes, dried fruit, flaxseed, olive oil, or coffee) to initiate or maintain bowel movements. Unlike occasional use, this pattern suggests an underlying inability to evacuate without external stimulation.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from impaired colonic motility (reduced peristalsis, weakened gastrocolic reflex) and prolonged stool retention. Over time, the colon becomes conditioned to depend on stimulatory foods, masking latent dysfunction. May coexist with pelvic floor dyssynergia or slow-transit constipation.

Prevalence

In adults with self-reported constipation, approximately 16% use over-the-counter laxatives; however, habitual use of natural laxogenic foods is poorly studied. Surveys indicate that up to 40% of individuals with functional constipation regularly rely on foods, like prunes or flaxseed, to promote bowel movements, especially when avoiding pharmaceutical options.

Related Conditions

Dependence on laxatives, dependence on dietary fiber, straining, SIBO, hemorrhoids, anal fissures.

Diagnostic Implications

Reliance on laxogenic foods is often dismissed as health-conscious or natural. In latent constipation, however, it often reveals failed intrinsic motility and hidden bowel dysfunction.

Reversibility

Often reversible once colonic motility and reflexes are restored. Continued dependence signals progression toward structural or neurologic bowel damage.

11. Dependence on Dietary Fiber

Primary Symptoms

Routine reliance on fiber supplements, such as psyllium, bran, or prebiotic mixes, to trigger or normalize bowel movements. Patients often feel unable to move their bowels without regular fiber use.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from a weakened colonic reflex that no longer initiates motility independently. Latent constipation conditions the colon to depend on external bulk to produce stool, suppressing intrinsic peristalsis over time.

Prevalence

A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials including 1,251 adults with chronic constipation found that fiber supplementation (daily doses over 10 g for at least 4 weeks) significantly improved stool frequency and consistency, but 66% of fiber users also reported increased flatulence (Eswaran et al., 2022). Fiber use is standard first-line therapy in clinical guidelines and appears in over 50% of treatment plans for chronic constipation, despite limited evidence of long-term resolution.

Related Conditions

Dependence on laxatives, dependence on laxogenic foods, straining, flatulence, bloating, hemorrhoids

Diagnostic Implications

Reliance on fiber is often viewed as benign or healthy. In latent constipation, it signals ongoing motility failure: frequency remains, but function is impaired without the aid.

Reversibility

It can be reversed when bowel reflexes are retrained and natural motility restored. Ongoing fiber dependence despite daily bowel movements suggests progression toward organic constipation.

12. Absence of Strong Post-Meal Urge

Primary Symptoms

Weak or absent urgency to defecate following meals, despite routine bowel movements. Patients may feel nothing until prompted or constrained by time.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from the blunted gastrocolic reflex and rectal hyposensitivity. In latent constipation, the bowel adapts to reliance on external triggers, causing neural reflexes responsible for post-prandial urgency to diminish gradually.

Prevalence

In a cohort study of adults with functional constipation, 54% reported no urge or feeling of rectal fullness after meals, despite bowel movements occurring at least once daily (Philpott et al., 2019, Neurogastroenterology & Motility, DOI: 10.1111/nmo.13592). Studies of healthy controls show normal gastrocolic response in 80–90% of participants, underscoring the reflex impairment in constipated individuals.

Related Conditions

Straining, decreased rectal sensitivity, dependence on laxatives, loss of motility, feeling of incomplete evacuation, SIBO.

Diagnostic Implications

Often overlooked when stool frequency is preserved. The absence of normal urge reflex indicates neural adaptation and advancing latent constipation.

Reversibility

Partial to full recovery is possible if colonic transit is improved and natural reflexes are retrained through behavioral interventions or biofeedback.

13. Hemorrhoidal Disease

Primary Symptoms

Enlargement, swelling, or prolapse of the vascular cushions in the anal canal. Patients may report painless bleeding, itching, or discomfort during bowel movements and often describe a tender lump at the anus.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from increased intraluminal pressure and repeated straining on hardened or bulky stools. In latent constipation, mechanical stress on anal cushions leads to vascular engorgement, inflammation, and prolapse.

Prevalence

Anal symptoms consistent with hemorrhoids affect an estimated 4.4% of the global population, while up to one-third of US adults report hemorrhoid-related complaints within any one year (Haas & Haas, 1990; Medscape, 2022). Hemorrhoidal disease has been identified in 16.6% of healthy adults undergoing colonoscopic screening (Chi et al., 2021).

Related Conditions

Straining, pain during defecation, anal fissures, rectal prolapse, diverticular disease, SIBO, recurrent bleeding

Diagnostic Implications

Often treated as an isolated anorectal pathology. In the context of latent constipation, hemorrhoidal disease signals chronic stool burden and mechanical stress, and suggests broader colonic motility dysfunction.

Reversibility

Early-stage hemorrhoids often regress when stool consistency, transit, and straining are corrected. Persistent or advanced cases may require procedural intervention.

14. Anal Fissure

Primary Symptoms

A tear of the mucosal lining of the anal canal that causes sharp or burning pain during and sometimes after bowel movements. Patients may also notice bright red blood on the stool or toilet paper.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from mechanical trauma: hard or bulky stool stretches the anal mucosa, often combined with increased anal sphincter pressure during straining. In latent constipation, weak colonic motility and impaired stool reflexes cause passage of firm stool that injures the mucosa, leading to fissure formation.

Prevalence

Anal fissure has an annual incidence of approximately 0.11% in general practice, peaking at 0.18% among adults aged 25–34 (The epidemiology and treatment of anal fissures, 2014) with up to 40% of cases linked to chronic constipation on presentation (Alomair et al., 2019). One study in reproductive-age women found a 15% prevalence, with chronic constipation as a significant risk factor (mayoclinic.org, jsogp.net) (mayoclinic.org, jsogp.net).

Related Conditions

Hemorrhoids, straining, pain during defecation, rectal prolapse, dependence on stimulants, SIBO.

Diagnostic Implications

Often attributed to isolated anorectal pathology. In latent constipation, fissures indicate mechanical injury from unresolved stool hardness and underlying bowel dysfunction, even in regular defecators.

Reversibility

Most acute fissures heal with stool softening, dietary adjustments, and improved transit. Chronic fissures may require topical treatments or sphincterotomy if motility issues persist.

15. Rectal Prolapse

Primary Symptoms

Partial or complete protrusion of the rectal wall through the anal canal, occurring during straining or after a bowel movement. Patients may describe a visible or palpable mass at the anus, often accompanied by discomfort or soiling.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from repeated straining against hard or bulky stools, leading to stretching and weakening of the pelvic floor and rectal supportive structures. In latent constipation, weakened motility and persistent reliance on forced evacuation increase intrarectal pressure and facilitate tissue descent.

Prevalence

Community-based studies report that full-thickness rectal prolapse occurs in approximately 0.5 per 100,000 children and 2.5 per 100,000 adults annually (Baumann et al., 2020, Colorectal Disease, DOI: 10.1111/codi.15205). Prolapse is more common in older adults and those with chronic straining due to constipation or pelvic floor dysfunction.

Related Conditions

Straining, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, incomplete evacuation, SIBO, pelvic floor disorders,

Diagnostic Implications

Often treated surgically without evaluating the underlying bowel function. In latent constipation, prolapse indicates long-standing anorectal strain and should prompt assessment of motility and stool consistency.

Reversibility

Early mucosal prolapse may reverse with normalization of stool and cessation of straining. Full-thickness prolapse typically requires surgical repair along with correction of bowel habits to prevent recurrence.

16. Intermittent Diarrhea

Primary Symptoms

Episodes of loose or watery stools alternating with periods of firm, difficult-to-pass stools or constipation. Patients may report sudden urgency during diarrhea episodes and normal or reduced frequency during constipation phases.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from overflow incontinence or irritation caused by impacted stool. In latent constipation, fecal stagnation can lead to plaque-like impaction or bacterial overgrowth, triggering periodic loose stools that pass around retained fecal masses. This condition is called ‘paradoxical diarrhea.’

Prevalence

In general adult populations, chronic diarrhea affects 1–5% of individuals. Studies show that up to 60% of patients with IBS‑C or functional constipation report alternating constipation and diarrhea, indicative of intermittent diarrhea linked to transit irregularity and latent bowel dysfunction (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Related Conditions

IBS‑C, SIBO, bloating, flatulence, straining, reduced urge after meals.

Diagnostic Implications

Intermittent diarrhea is typically attributed to IBS‑M or dietary triggers. When associated with other symptoms of latent constipation, it may instead reflect stool impaction and overflow, signaling deeper motility impairments.

Reversibility

Often reversible once bowel transit is normalized and stool burden is reduced. Persistent alternation suggests progression toward mixed or organic dysfunction if untreated.

17. Diverticular Disease

Primary Symptoms

Outpouchings of the colon wall called diverticula may cause cramping, altered bowel function, and bleeding.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from high intraluminal pressure from bulky or hardened stool and chronic straining. In latent constipation, delayed transit and mechanical stress on the colon wall weaken muscle layers, allowing mucosal herniation.

Prevalence

In Western populations, diverticulosis affects up to 60% of individuals over age 60 and 5–45% of those over age 40 (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Studies link constipation with an increased hazard for acute diverticulitis—approximately 15% increased risk per constipation severity point in symptom scales (irjournal.org).

Related Conditions

Straining, hemorrhoids, SIBO, intermittent diarrhea, abdominal pain, anal fissures.

Diagnostic Implications

Diverticular disease is often managed as a dietary or age-related issue. Within latent constipation, its presence signals chronic bowel dysfunction and significant mechanical stress on the colon.

Reversibility

Diverticulosis does not reverse fully, but progression—stricture, bleeding, or diverticulitis may be prevented by normalizing bowel habits and reducing intraluminal pressure.

18. Redundant Colon (Dolichocolon)

The term dolichocolon literally means “elongated colon,” from the Greek dolicho (δολίχος), meaning extended. It is a medical term used to describe a colon that is longer than normal, often with extra loops or redundancy. This anatomical variation can slow stool transit and contribute to chronic constipation.

The term has been used in gastrointestinal literature for over a century. It was formally described in radiographic studies in the early 20th century, particularly through barium enema imaging, which revealed these anatomical variations more clearly.

After death, the colon can be stretched to up to twice its resting length and diameter due to complete muscle relaxation. This demonstrates that the anatomical capacity for distention already exists under passive conditions.

Another commonly used term for the same condition is tortuous colon, although this term may also refer to increased diameter or exaggerated looping, not just elongation.

Primary Symptoms

An abnormally long colon forming extra loops and tortuous segments, often detected via imaging or colonoscopy. Patients may not know it exists until complications arise.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from chronic overstretching and distension of the colon due to repeated retention of large or hard stools. Latent constipation leads to prolonged colonic transit time, weakening muscle tone, and creating anatomical redundancies.

Prevalence

Clinical studies report dolichocolon in 1.9 percent to 28.5 percent of adults undergoing imaging for bowel symptoms. In a tertiary care cohort with constipation, 63 percent met criteria for redundancy on CT or transit studies (Dilmaghani et al., 2024 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38697236/; Raahave, 2018 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29492185/).

Related Conditions

Constipation, bloating, abdominal pain, straining, diverticular disease, intermittent diarrhea, volvulus.

Diagnostic Implications

Often dismissed as a normal anatomical variant. In latent constipation, redundancy signals indicate advanced structural adaptation from chronic motility compromise and stool burden.

Reversibility

Structural redundancy may be permanent, but symptom control is possible with normalized transit and stool volume. In refractory cases with obstruction or volvulus, surgery may be required alongside treating underlying latent constipation.

19. Colon Distention Noted During Colonoscopy

Primary Symptoms

Endoscopists observe an abnormally enlarged or distended colon during colonoscopy. This is typically not purposefully looked for but noticed when insufflated air fails to reduce colonic lumen size.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from chronic retention of large stool volumes and prolonged gas accumulation. In latent constipation, slow transit and incomplete evacuation cause gradual colonic stretching. During colonoscopy, even insufflation cannot revert this baseline distension.

Prevalence

A prospective series of patients undergoing colonoscopy for constipation showed mild to moderate colonic distention in approximately 20–30 percent of cases without evidence of obstruction (frontiersin.org). A case report of colonic inertia similarly documented pan-colonic dilation in the absence of mechanical causes (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Related Conditions

Redundant colon, bloating, abdominal pain, straining, intermittent diarrhea, SIBO.

Diagnostic Implications

Distention is often attributed to acute over-insufflation or bowel preparation. However, when observed after sufficient air insufflation, it indicates pre-existing colonic dilation from chronic stool retention, a hallmark of latent constipation.

Reversibility

Early-stage distention may improve with normalization of transit and stool reduction. Long-standing dilatation—colonic redundancy-is—is usually permanent, but symptoms can still be managed.

20. Megacolon

Primary Symptoms

A pathologic enlargement of the colon marked by excessive diameter, not length. Diagnostic thresholds typically include a transverse colon over 6 cm, sigmoid colon over 10 cm, or cecum over 12 cm Patients may present with abdominal distention, constipation, cramping, and, in acute forms, fever and systemic signs.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Results from prolonged stool retention and chronic intraluminal pressure. In latent constipation, gradual loss of motility and persistent colonic stretch may eventually cause irreversible neuromuscular dysfunction, leading to megacolon.

Prevalence

Chronic megacolon is rare but recognized in long-standing constipation and colonic inertia. A review of radiographic cases found sigmoid diameters ≥10 cm in patients with refractory symptoms. Toxic megacolon, an acute complication of colitis, affects 1% to 4% of hospitalized IBD patients.

Related Conditions

Colonic inertia, abdominal distention, palpable stool, SIBO, ischemic colitis, perforation, rectal prolapse.

Diagnostic Implications

Megacolon is distinct from colon distention observed during colonoscopy. It represents a structural and functional endpoint, often requiring radiologic confirmation and, in some cases, surgical evaluation. Chronic latent constipation is a known predisposing factor.

Reversibility

Chronic megacolon is typically irreversible, though symptom control is possible with aggressive bowel management. Acute toxic megacolon is a medical emergency. Identifying and treating latent constipation early may prevent progression to megacolon.

21. Non‑Genetic Polyp Formation

Primary Symptom Description

Development of one or more growths (polyps) on the colon lining in individuals over age 50, without underlying genetic syndromes. Most polyps are asymptomatic but may occasionally cause bleeding, altered stool caliber, or obstruction if large.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

Polyps form primarily due to genetic and cellular changes in the colonic epithelium, often influenced by age, diet, inflammation, and metabolic factors. In the context of latent constipation, chronic stool retention increases mucosal exposure to mechanical pressure, fermentation byproducts, and bile acids. This prolonged contact time may contribute to local inflammation, oxidative stress, and epithelial remodeling—factors that can support polyp development in susceptible individuals.

Prevalence

While colorectal screening now begins at age 45, the prevalence of adenomatous polyps rises significantly after 50, particularly in those with chronic bowel dysfunction. Polyps are found in 20–30% of average-risk adults over age 50 during screening colonoscopies (Lieberman et al., 2008). In large Asian cohorts, prevalence reaches 35% in men by age 60

Cancer Potential

Approximately 5–10% of adenomatous polyps progress to colorectal cancer over 10–20 years if left untreated. Risk increases with polyp size, histologic type (villous or serrated), and presence of dysplasia. Polyps larger than 10 mm carry the highest malignant potential. Apologies for the technical language in this section. Unfortunately, there is no simple way to explain how colorectal cancer develops.

Related Conditions

Colorectal cancer, intermittent diarrhea, altered stool caliber, straining, bleeding, constipation.

Diagnostic Implications

Polyps in adults over 50 are typically considered age-related. In the context of latent constipation, their presence may instead reflect longstanding mucosal strain from retained stool and poor motility, especially in patients with other symptoms.

Reversibility

Polyps themselves must be removed endoscopically to eliminate cancer risk. Treating latent constipation may help reduce recurrence by lowering mechanical and inflammatory stress on the mucosa.

22. Appendectomy in Adults

Primary Symptoms

History of surgical removal of the appendix in adulthood following acute appendicitis. Most patients recover fully, and the procedure is often considered a resolved event with no long-term implications.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

In adults, appendicitis often results from fecalith obstruction at the base of the appendix. A fecalith is a hardened mass of stool that forms into a stone-like material of varying size. The related term fecaloma, used in the context of fecal impaction, refers to a giant fecalith. Apologies for the pun, but much shit happens down there, and the medical profession has a name for every one of them.

Latent constipation increases the likelihood of this obstruction by promoting stool impaction. The prolonged presence of firm stool in the cecum and ascending colon can compress or block the appendiceal lumen (cavity) and trigger inflammation.

Why Pediatric Cases Are Excluded

In children and adolescents, appendicitis is more likely to result from lymphoid hyperplasia, viral triggers, and obstruction with undigested food particles, such as bones, pits, and skins, rather than fecaliths. These cases do not typically reflect a history of chronic constipation and are therefore less relevant to the context of latent bowel dysfunction.

Prevalence

Appendectomy is performed in approximately 1% of the U.S. population per decade, with over 300,000 cases annually. In adult appendicitis, fecaliths are present in up to 40% of cases.

Related Conditions

IBS, SIBO, straining, altered stool patterns, slow transit constipation.

Diagnostic Implications

Appendectomy in adults may serve as historical evidence of severe right-colon fecal stasis and latent constipation. Postoperative changes in microbial and motility patterns may persist, especially if no dietary or lifestyle corrections were made.

Reversibility

The surgery is permanent, but functional consequences such as residual slow transit or altered gut flora can often be improved by addressing the underlying latent constipation and optimizing motility.

23. SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth)

Primary Symptoms

Excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine causes bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and sometimes diarrhea or constipation.

Mechanism / Cause in the Context of Latent Constipation

In patients with latent constipation, feces reflux back into the small intestine after the large intestine fills to the rim. Incomplete emptying of stools is the primary cause of this condition. In some cases, it is exacerbated by an ileocecal valve defect. Under normal circumstances, this sphincter between the small and large intestines remains tightly shut and only opens to allow the contents of the small intestine to pass into the large intestine and be converted into stools.

Prevalence

A 2020 meta-analysis of 3,192 IBS patients and 3,320 controls found methane-positive SIBO in 25.3% of IBS-C patients versus 8.8% of IBS-D patients (OR ≈ 3.5 for methane SIBO in constipation cases) (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, time.com). SIBO occurs in approximately 14–25% of individuals with motility disorders or chronic constipation.

Related Conditions

Bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain, intermittent diarrhea, reduced motility, straining.

Diagnostic Implications

SIBO is often diagnosed when patients report IBS-like symptoms. In latent constipation, its presence reflects upstream bacterial stagnation due to slow transit and impaired reflexes.

Reversibility

Responsive to targeted treatment (antibiotics or dietary) combined with restoration of normal motility. If underlying transit issues are not addressed, recurrence rates are high.

Takeaways

A few years ago, a client told me that his GI doctor described his twice-a-week bowel movement as “normal for him.” He didn’t think much of it until he needed emergency surgery for a ruptured diverticulum. That’s how latent constipation is usually discovered. Too late.

Latent constipation refers to incomplete or strained bowel movements that appear “regular” by clinical or social standards but require effort, triggers, or workarounds to maintain.

It is a silent condition—often undiagnosed and mischaracterized—that precedes a wide range of colorectal disorders, including polyps, megacolon, IBS, IBD, and colorectal cancer.

A total of 23 early indicators of latent constipation are outlined in this article. They are measurable, progressive, and commonly dismissed by patients and physicians alike.

Many of these indicators appear decades before formal diagnosis and are often first visible in late adolescence or early adulthood. Left uncorrected, latent constipation becomes organic constipation—structural, irreversible, and often requiring surgical intervention.

Most patients with colorectal cancer, diverticular disease, or severe hemorrhoids report long-standing bowel irregularities that were normalized, self-treated, or ignored.

Clinical guidelines and diagnostic norms—such as the Merck Manual definition of constipation—miss most early signs because they are based on frequency, not effort or completeness.

Common treatments like fiber, laxatives, and hydration may conceal symptoms temporarily, but do not reverse the underlying pathology. In many cases, they contribute to it.

Recognition and correction of latent constipation is possible and most effective in its early stages. Once the transition to organic damage occurs, dietary and lifestyle changes are no longer sufficient.

If your work or lifestyle keeps you seated on your behind for most of the day, the least you can do for yourself is pay attention to what, when, and how things come out of it. It may not seem urgent now, but by the time the proverbial ‘pain in the ass’ becomes real, it may be too late to fix.

Author's Note

After 25 years of studying constipation, I guess that makes me a leading expert in crapology. It's not exactly a glamorous field, but someone had to get to the bottom of it.

One of the most important things that I learned — it’s never too late to start reversing colorectal damage. Some of the conditions described above may already be in full swing, but that doesn’t mean they’re irreversible. Even a partial reversal is better than none.

In my case, I first noticed an external hemorrhoidal bump when I was 19 years old. I suffered from excruciatingly painful external hemorrhoids into my late forties. Until early 2000, every trip to the bathroom was a dreaded and painful affair, often with a streak of blood from internal hemorrhoids. Severe IBS kept me in constant pain from my mid-thirties. Switching to a vegan lifestyle to stuff myself with more fiber and water only made matters worse.

I discovered the constipation ‘miracle’ of Hydro-CM by accident in 2000 while helping a client find a diet that would work for her after losing her stomach to cancer surgery. To make sure the recommendations were sound, I tested them on myself first and noticed the formula's pronounced laxogenic effect.

If you aren’t yet familiar with Hydro-CM, unlike commercial laxatives, this hypoallergenic formula acts as a ‘colonic moisturizer,’ stimulates natural and on-demand bowel movements within 40 to 60 minutes, is non-addictive, and supplies essential calcium, magnesium, and vitamin C. [Mechanism of action] [Benefits].

As I looked deeper, I found that Dr. Linus Pauling, the only person to receive two unshared Nobel Prizes, had experienced something similar. He reportedly took 10 grams of vitamin C a day for much of his later life and lived to 93.

The discovery of fiber’s harm came in 2003 while I was investigating the causes of constipation associated with the then-popular Atkins Diet. Along with Hydro-CM, these insights transformed my colorectal health and gave me the conviction to write about this subject and share the supplements with my readers and clients.

Despite all of the prior damage, most of it irreversible, I have been free of latent constipation and related problems ever since.

Please don’t keep this information to yourself. Share it with your siblings, children, and grandchildren. Families tend to pass down not only genes but also bad habits. Help your relatives to fix them, and the earlier they do it, the better.