How to Check If Your Stool Is Normal?

Your stool is a crystal ball for your health that, ideally, you get to see every day. Its appearance and smell can reveal more about your gut health, diet, and digestion than an annual physical, and it's free to boot.

That’s, incidentally, why paranoid heads of state do not use public bathrooms while on state visits abroad. Host country intelligence agencies often collect their stool and urine samples to assess their health, medications, genomes, and other insightful markers.

In that spirit, I wrote this guide to help you analyze your own stool the way a spy agency might analyze a world leader’s. All you need is good lighting, good eyes, and a good nose.

If you are obsessive-compulsive over your bodily functions, you may want to record the foods, fluids, and supplements you consume, along with the timing and characteristics of your bowel movements, including stool appearance, bloating, and flatulence. This will help you observe the connection between what goes in and what comes out.

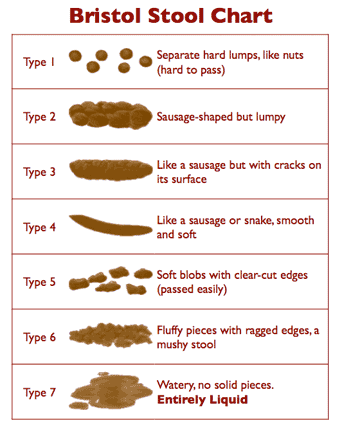

Bristol Stool Form Scale

The Bristol Stool Form scale, or the BSF scale for short, is a self-diagnostic chart designed to help skittish patients discuss this delicate subject with their doctors without getting embarrassed.

The 'Bristol' in the BSF refers to the Bristol Royal Infirmary — a hospital in Bristol, England — from where this scale originated. You just look at the picture, point to what approximates the content of your toilet bowl, and your doctor tells you whether your type is good or bad:

» Type 1: Separate hard lumps, like nuts

Typical for acute dysbacteriosis. These stools lack a normal amorphous quality because bacteria are missing, and there is nothing to retain water. The lumps are hard and abrasive, the typical diameter ranges from 1 to 2 cm (0.4–0.8”), and they‘re painful to pass because the lumps are hard and scratchy. There is a high likelihood of anorectal bleeding from mechanical laceration of the anal canal. Typical for post-antibiotic treatments and people attempting fiber-free (low-carb) diets. Flatulence isn‘t likely because fermentation of fiber isn‘t taking place.

» Type 2: Sausage-like but lumpy

Represents a combination of Type 1 stools impacted into a single mass and lumped together by fiber components and some bacteria. Typical for organic constipation. The diameter is 3 to 4 cm (1.2–1.6”).

This type is the most destructive by far because its size is near or exceeds the maximum opening of the anal canal‘s aperture (3.5 cm). It‘s bound to cause extreme straining during elimination and most likely to cause anal canal laceration, hemorrhoidal prolapse, or diverticulosis.

To attain this form, the stools must be in the colon for at least a week or more instead of the normal 72 hours. Anorectal pain, hemorrhoidal disease, anal fissures, withholding or delaying of defecation, and a history of chronic constipation are the most likely causes. Minor flatulence is probable.

A person experiencing these stools is most likely to suffer from irritable bowel syndrome because of the continuous pressure of large stools on the intestinal walls. The possibility of obstruction of the small intestine is high because the large intestine is filled to capacity with stools.

Adding supplemental fiber to expel these stools is dangerous because the expanded fiber has no place to go and may cause a hernia, obstruction, or perforation of the small and large intestines alike.

» Type 3: Like a sausage but with cracks in the surface

This form has all of the characteristics of Type 2 stools, but the transit time is faster between one and two weeks. Typical for latent constipation. The diameter is 2 to 3.5 cm (0.8–1.4”). Irritable bowel syndrome is likely. Flatulence is minor because of dysbacteriosis. The fact that it hasn‘t become as enlarged as Type 2 suggests that the defecations are regular. Straining is required. All of the adverse effects typical for Type 2 stools are likely for type 3, especially the rapid deterioration of hemorrhoidal disease.

» Type 4: Like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft

This form is normal for someone defecating once daily. The diameter is 1 to 2 cm (0.4–0.8”). The larger diameter suggests a longer transit time or a large amount of dietary fiber in the diet.

» Type 5: Soft blobs with clear-cut edges

I consider this form ideal. It is typical for a person who has stools twice or three times daily after major meals. The diameter is 1 to 1.5 cm (0.4–0.6”).

» Type 6: Fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool

This form is close to the margins of comfort in several respects. First, it may be difficult to control the urge, especially when you don‘t have immediate access to a bathroom. Second, it is a rather messy affair to manage with toilet paper alone unless you have access to a flexible shower or bidet. Otherwise, I consider it borderline normal.

This kind of stool may suggest a slightly hyperactive colon (fast motility), excess dietary potassium, or sudden dehydration or spike in blood pressure related to stress (both cause the rapid release of water and potassium from blood plasma into the intestinal cavity). It can also indicate a hypersensitive personality prone to stress, too many spices, drinking water with a high mineral content, or the use of osmotic (mineral salts) laxatives.

» Type 7: Watery, no solid pieces

This type, of course, is diarrhea, a subject outside the scope of this chapter with just one important and notable exception — so-called paradoxical diarrhea. It‘s typical for people (especially young children and infirm or convalescing adults) affected by fecal impaction — a condition that follows or accompanies type 1 stools.

During paradoxical diarrhea, the liquid contents of the small intestine (up to 1.5–2 liters/quarts daily) have no place to go but down because the large intestine is stuffed with impacted stools throughout its entire length. Some water gets absorbed, and the rest accumulates in the rectum.

The reason this type of diarrhea is called paradoxical is not because its nature isn‘t known or understood but because being severely constipated and experiencing diarrhea all at once is, indeed, a paradoxical situation. Unfortunately, it‘s all too common.

Interestingly, the interpretations and explanations of the BSF scale that accompany the original chart differ from my analysis. To this, I can only say: thanks for the great pictures, but no thanks for the rest.

Latent constipation is the term that I coined back in 2005 in my book titled Fiber Menace: The Truth About the Leading Role of Fiber in Diet Failure, Constipation, Hemorrhoids, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn's Disease, and Colon Cancer.

If you aren't familiar with Fiber Menace, brief information is in order because I'll be referring to this term many times throughout this page, and its understanding is essential to the understanding of stool abnormalities described on this page.

A generation or so ago, the term “costivity” was broadly used to describe hard stools and straining, while the term “constipation” was used to describe “irregularity,” meaning “a failure to move the bowels daily.”

Since then, the terms costivity and constipation have blended into one, while the “failure to move the bowels for three consecutive days” has become the 'official' definition of clinical constipation.

On the other hand, painful and bloody stools within these three days have become a mere irregularity, or a doctor-speak for “don't bore me with your problems until the fourth day.”

In practical terms, this means that the definition of “constipation” has become too vague and unspecific — a situation akin to doctors not knowing the location of your heart or liver. Indeed, how can you get proper treatment when constipation for you means “pain while moving the bowels,” while it may mean the “failure to move the bowels for three consecutive days” for your doctor?

For this and other practical reasons, I reclassified constipation (see Fiber Menace, p.p. 97-128 for more details) into three distinct stages: functional (reversible), latent (hidden), and organic (irreversible):

Functional constipation. This condition commonly follows a stressful event, surgery, colonoscopy, diarrhea, temporary incapacity, food poisoning, treatment with antibiotics, the side effects of new medication — the circumstances that damage intestinal flora, interfere with intestinal peristalsis, or both. A person becomes irregular, stools correspond to the BSF scale type 1 to 3, and straining is required to move the bowels. The person resorts to fiber or laxatives for help.

Latent constipation. If the intestinal flora, stools, and peristalsis aren't properly restored following adverse event(s), functional constipation eventually turns into the latent form (i.e., hidden) because fiber‘s or the laxative's effects on stools create the impression of normality and regularity. The stools become larger, heavier, and harder, usually, the BSF type 3, straining more intense, but for as long as you keep moving your bowels every so often and without too much pain, there is still an impression of regularity. This is, by far, the most dangerous form of constipation because of what happens next...

Organic constipation. As time goes by, large and hard stools — between type 2 and 3 — keep enlarging internal hemorrhoids and stretching out the colon. This, in turn, reduces the diameter of the anal canal even more, causes near complete anorectal nerve damage, and slows down or cancels out completely the propulsion of stools alongside the colon (motility). At this juncture, the person no longer senses a defecation urge and becomes dependent on intense straining and/or laxatives to complete a bowel movement. If you don't use 'hard' laxatives, you fail to move the bowels even with a good helping of fiber. That is, in fact, what most people mean nowadays when they say: “I have been diagnosed with constipation.”

So, as you can see, you can indeed use fiber to coax your bowels into regularity for a good while, but at the expense of enlarged stools. At some point in that 'while,' you'll also end up with damaged bowels and a life-long dependence on more and more fiber and 'hard' laxatives.

How long that 'while' may last depends on how early you get started with this crazy therapy. If you are in your teens today, you'll pay the price in your early forties. If you are in your early forties, damnation will come by your early fifties. If you are a woman, things will go downhill even faster for reasons explained on this page: Why Women Get Constipated More Often Than Men?

With the BSF scale and Latent constipation explanations completed, let's go to the 'meats and potatos' of stool morphology!

Quantitative stool characteristics

Quantitative (related to quantity) stool characteristics refer to measurable properties such as frequency, weight, length, diameter, moisture, and transit time. These metrics provide objective data that can be tracked over time and compared against clinical norms.

They differ from qualitative (related to quality) characteristics further down this page, which are based on visual, tactile, or olfactory observations like color, texture, and odor. While qualitative traits offer immediate clues about stool composition and digestion, quantitative markers are better suited for identifying trends, assessing severity, and evaluating improvements or declines.

Stool Weight

The total weight of stool per bowel movement is primarily influenced by the presence of insoluble (same as indigestible) fiber.

In pre-industrial societies, high fiber intake was mostly common among the very poor, who had no access to meats, fish, and milled flour and primarily subsisted on a plant-based diet.

Their stools were bulky and frequent. In modern settings, most people consume low- to moderate-fiber diets unless intentionally supplementing with processed fiber or fiber supplements or following vegetarian/vegan lifestyle.

Water isn’t a significant contributor to stool weight. Normal formed stool contains between 70% and 75% water. Anything above it causes diarrhea. In fact, dehydrated stools become smaller and lighter, not larger and harder.

Non-fibrous food contributes little weight to stool bulk. Proteins, fats, and processed carbohydrates without added fiber are digested and absorbed almost completely. The undigested residue of food typically makes up under 5% of the total stool weight.

Thus, even if a person eats two times more low-density food without added fiber, the weight of their stool will only rise from 5 grams per 100 grams of stool to 10 grams, which is not enough to change the total stool output significantly.

Normal range

Typical adult stools weigh between 100 and 150 grams per evacuation. This range reflects modern mixed diets that include both digestible and indigestible components. Most healthy individuals fall into this bracket.

Abnormal range

Very low weight (<50 g). Often indicates reduced food intake, prolonged stool retention, slow transit, or partial evacuation. Common in chronic constipation. The stool may appear hard, dry, or fragmented.

Excessive weight (>200 g). Extra weight may reflect excessive fiber, latent constipation, or insufficient frequency of bowel movements. In this situation, stools increase in weight with each missed bowel movement.

Stool Frequency

Frequency refers to how often bowel movements occur, typically measured per day or week. It reflects the regularity of colonic motility and coordination of the defecation reflex.

Under ideal circumstances, healthy people should move their bowels after each major meal because the gastrocolic reflex triggers colonic contractions in response to stomach stretching. This reflex promotes the movement of stored feces toward the rectum.

In well-functioning systems, this process results in one to three bowel movements per day, each occurring shortly after a large meal. Regular evacuation after meals prevents stool retention, prevents colon distention, and ensures consistent stool quality.

Unfortunately, this "normal" pattern is disrupted in modern settings because people may lack immediate access to a clean, private bathroom after meals, especially at work, in schools, or during commutes.

Public restrooms may be unsanitary, crowded, or socially awkward to use for defecation. These constraints suppress the natural urge and delay evacuation, leading over time to stool retention, longer transit, harder stools, and latent constipation.

Frequency alone doesn’t define pathology. A person with one effortless stool every other day may be healthy if stool size, weight, ease of passage, and absence of symptoms are normal. Likewise, 2 to 3 smaller bowel movements per day may be healthy in individuals with active gastrocolic reflexes and more daily meals, which is typical for healthy and active younger men and women.

That said, low frequency, even when asymptomatic initially, may lead to stool retention, hardening, and progressive anorectal damage. In elderly individuals, the low frequency is common due anorectal damage and decreased motility. In children, it may result from withholding behavior.

Normal Range

1 to 3 times per day. Most healthy individuals fall within this range. Once-daily is most common, often in the morning after waking or after breakfast, due to the gastrocolic reflex.

3 times per week to 3 times per day is considered clinically acceptable. Variations within this range are benign if not associated with discomfort, pain, or other abnormal stool characteristics.

Abnormal range

Fewer than 3 bowel movements per week. This is the clinical threshold for diagnosing constipation. Often accompanied by straining, hard stools, incomplete evacuation, or bloating.

More than 3 bowel movements per day. Suggests rapid transit. Common causes include dietary shifts, infections, laxative use, malabsorption, or inflammatory disorders. If stools are loose or urgency is present, further evaluation may be needed.

Stool Diameter

Refers to the cross-sectional thickness of stool. Influenced by stool volume, hydration, colonic tone, and the width of the anal canal. Diameter is measured in cm or compared to finger width. Normal range: ~1.5–2.5 cm.

Normal range

In healthy individuals with regular evacuation and adequate hydration, stool diameter typically reflects the natural resting tone and distensibility of the rectum and anal canal. Stool size may vary slightly from day to day, but the consistent passage of moderate-caliber stools without strain is a reliable marker of functional motility.

The diameter roughly equal to the index or middle finger. Indicates timely evacuation with normal colonic pressure and unobstructed anorectal passage. This size is the most common and physiologically neutral range.

Smaller-caliber stool. It may occur in individuals with softer or faster stools, reduced bulk from low-residue diets, or anatomical differences. Acceptable if not accompanied by fragmentation, frequency changes, or sensation of incomplete emptying.

Variable size. Occasional fluctuation in diameter, when not associated with discomfort or difficulty, falls within normal variation, especially with dietary shifts or transient withholding.

Abnormal range

Persistent deviations in stool caliber can reflect mechanical restriction, retained mass, or disordered colonic tone. Size abnormalities often coincide with changes in shape, effort, or frequency.

Large-caliber stool. Often caused by prolonged stool retention, excessive fiber, or incomplete evacuation. It may reflect a distended rectum or colon from chronic constipation. Associated with a higher risk of fissures, hemorrhoids, and nerve desensitization.

Very small-caliber stools. When persistent, it may indicate increased anal pressure, chronic spasm, or external compression. Thin stools may also result from narrowing due to internal scarring, advanced hemorrhoids, or colorectal tumors, especially if accompanied by blood, weight loss, or altered smell.

Stool Length

This parameter refers to the linear measurement of stool during the passage. It reflects the holding capacity of the colon—specifically the descending and sigmoid segments—before evacuation.

Normal range

The sigmoid colon is typically 25 to 40 cm (10 to 16 inches) in length. The rectum adds another 12 to 15 cm (5 to 6 inches). Most well-formed stools are limited to this combined length, so a typical bowel movement measures between 20 and 50 cm (8 to 20 inches).

Abnormal range

Very short stools (<20 cm / <8 inches) may reflect partial evacuation, a weak gastrocolic reflex, or storage limited to the rectum. Common first thing in the morning.

Excessively long stools (>60 cm / >24 inches) suggest chronic retention extending into the descending colon. This is seen in cases of slow transit constipation, colonic redundancy, or impaction.

Segmented stools with abrupt transitions or irregular shapes may signal spasmodic motility, uneven hydration, or partial obstruction.

Stool length provides indirect insight into transit time and bowel usage. Evacuations limited to rectal length suggest prompt reflexes. Lengths exceeding the sigmoid colon imply backlog, poor motility, or delayed defecation, especially when infrequent and dense.

Other Qualitative Clinical Markers

There are, of course, other clinically relevant parameters that only a specialized lab can measure, and they include:

Moisture Content (%). Normal range: 70–75%. Below 65% indicates hard or dry stools; above 85% is typical of diarrhea.

Acidity. Normal adult range: 6.6–7.6 pH. Deviations may reflect excess fermentation, infection, or altered gut flora.

Fat Content (%). Should be less than 6% of dietary fat intake. Higher values suggest fat malabsorption (steatorrhea).

Occult Blood (ng/mL or mg/g). Abnormal if over 50–100 ng/mL, depending on test type. Indicates possible bleeding from tumors, ulcers, or inflammation.

Bacterial Load (CFU/g). Colony-forming units per gram of stool. Markedly reduced after antibiotics or in dysbiosis.

Electrolyte Concentration (Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻). Useful in evaluating diarrhea types; abnormal levels suggest secretory or osmotic imbalance.

Parasites. May require specialized tests for identification, including antigen assays or concentration techniques.

Qualitative stool characteristics

Qualitative characteristics are based on direct observation of stool appearance, texture, odor, surface features, and other visible or olfactory characteristics. Cumulatively, they provide insight into how the digestive process is functioning and whether there are signs of disease. While not always precise, qualitative parameters often reveal patterns that lab tests may overlook, especially when evaluated regularly.

This type of observational analysis requires attention and awareness and can literally save your life. And in between, make it far more enjoyable and free of bloating, flatulence, constipation, diarrhea, enlarged hemorrhoids, anal fissures, diverticular disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and non-genetic colorectal cancers.

All that you need is a glance into the toilet bowl and a check of the toilet paper after a swipe. And, of course, reading this page to the end.

Stool Color

Visual hue and tone are affected by bile, transit time, impaction, and oxidation.

Normal range

Normal stool color ranges from pale yellow to dark brown. This variation reflects the concentration and chemical state of bile pigments, primarily stercobilin, which is produced by the bacterial breakdown of bilirubin, a yellow pigment produced during the breakdown of old red blood cells in the intestines.

Lighter yellow/brown stools often result from faster transit or lower bile concentration, while darker shades reflect slower transit or higher levels of oxidized bile pigments.

Temporary shifts within this range can also result from diet, supplements, and medication, but in the absence of other abnormalities, yellow and brown in any tone between tan and deep mahogany is considered physiologically normal.

-

Pale-yellow to yellowish-brown. Common in individuals with faster transit times. Also typical in infants and toddlers due to immature bile metabolism and rapid digestion. Not pathological if other characteristics remain within normal range.

-

Medium brown. This color is the most common color of adult stool. It reflects the normal breakdown of bile pigments into stercobilin by intestinal bacteria. Variation in shade depends on bile concentration, oxidation, and transit time.

-

Dark brown. Considered normal if there are no other pathologies. Indicates longer transit time. It may indicate latent constipation and incomplete emptying.

-

Temporary reddish or darkening. These variations are transient and harmless when related to known causes. It may result from foods with strong coloring pigments, such as beets, wine, chocolate, iron supplements, or medications with bismuth. Typically resolves within 24 to 48 hours after removing the cause.

Abnormal range

Stool colors that fall outside the yellow/brown spectrum typically indicate a disruption in bile flow or hepatic (liver) functions. Persistent discoloration warrants attention when accompanied by other anomalies discussed on this page:

-

Pale white, gray, or clay-colored. Indicates a lack of bile pigment reaching the colon. Common causes include bile duct obstruction, cholestasis, or severe liver dysfunction.

-

Green. Usually caused by rapid transit that limits bile pigment oxidation, green food dyes, high intake of green vegetables, supplements (chlorophyll, chlorophyllin, iron sulfate, or iron fumarate), or laxatives that increase intestinal transit time. It isn’t abnormal unless accompanied by diarrhea or other pathologies.

-

Black. When not caused by iron or bismuth, it may indicate bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract. It should be distinguished from dietary causes and confirmed by Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) strips if persistent or accompanied by fatigue or abdominal pain.

Black stool can appear after eating certain foods or taking supplements rich in dark pigments. Iron supplements, multivitamins containing iron, or iron-rich foods such as liver and red meat often darken the stool.

The same effect can follow meals with black licorice, blueberries, blackberries, or large amounts of dark chocolate. Some pastries and candies colored with artificial black dyes can have a similar result.

If the stool stays black after these foods are excluded, it may indicate bleeding in the stomach or upper small intestine, commonly from ulcers or prolonged use of anti-inflammatory drugs.

-

Streaks of bright red. Indicates fresh blood on the surface of the stool, usually from hemorrhoids or anal fissures. Red mixed into the stool itself may suggest bleeding higher in the colon or rectum and should be evaluated further.

-

A small amount of blood along with white mucus. If not accompanied by other symptoms, it may indicate localized tissue inflammation or ulceration in the rectum, sigmoid colon, or descending colon. The blood is usually bright red or maroon and mixed with stool rather than coating it. A common cause is ulcerative colitis. In rare cases, it may reflect tumor necrosis (an advanced stage of colorectal cancer) in that area. A tumor is usually accompanied by unexplained weight loss.

When you notice abnormal stool color or other irregularities that persist for more than a few days, you must consult a physician. Persistent changes can signal internal bleeding, infection, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, or impaired bile flow from the lgallbladder. Early evaluation helps identify the cause before it leads to more serious complications or chronic conditions.

Stool Shape/Form

External contour or structural outline of the stool as shaped by colonic motility, stool moisture, and anorectal anatomy.

Normal range

Normal stool form reflects timely evacuation, balanced hydration, and intact peristaltic motion. In the absence of impaction, inflammation, or withholding, healthy stools maintain structural consistency but remain pliable.

-

Cylindrical, smooth, and unbroken. The most common and physiologically desirable form in adults. Indicates normal transit, adequate moisture, and intact bacterial fermentation. On the Bristol Stool Scale, typically type 4.

-

Soft segments with visible indentations. Considered normal, especially in individuals with higher motility or lighter stools. Slight segmentation is acceptable as long as the stool passes easily and completely.

-

Flat or ribbon-like stools. May reflect lower anal pressure or adaptive relaxation in the presence of pain, sensitivity, or hemorrhoids. It can be normal when other parameters (ease, frequency, color, and moisture) are within range.

-

Amorphous or loosely bound shapes. Common in infants, individuals taking laxatives, or during high-transit periods. Not pathological unless persistent or accompanied by urgency or incomplete evacuation.

Abnormal range

Deviations in stool form often indicate motility disruption, prolonged retention, or altered colonic tone. Structural anomalies may also reflect mucosal inflammation, pressure buildup, or anorectal dysfunction.

-

Hard, pellet-like pieces. Associated with slow transit, dehydration, or long retention. Often corresponds to type 1 or 2 on the Bristol scale. Common in chronic constipation or following withholding behaviors.

-

Thin, pencil-like stools. When persistent, it may suggest rectal stricture, enlarged internal hemorrhoids, or anal sphincter hypertonicity (spasm). These conditions should be evaluated if straining or pain is present.

-

Shapeless, mushy, or paste-like stools. In the absence of laxatives, this form may indicate mild mucosal inflammation (which impairs water reabsorption), high salt intake (which can retain excess water), certain naturally laxogenic foods (e.g., prunes, figs, high-sorbitol fruits), or incomplete fat absorption. While not immediately pathological, it is considered abnormal if persistent without identifiable dietary or pharmacologic triggers.

-

Flat but firm stools. Often reflects long-term adaptation to anorectal narrowing or sustained sphincter spasm. Usually accompanied by straining, discomfort, or pain. In such cases, evaluation and treatment are recommended. A colorectal tumor, particularly in the rectum or distal (further up) sigmoid colon, can also produce flat, ribbon-like, or narrowed stools. However, this is unlikely in the absence of additional signs such as blood and mucus in stool, unexplained weight loss, incomplete evacuation, or the characteristic stool odor associated with decaying tissue.

Stool Consistency

Stool consistency refers to internal firmness, continuity, and mechanical resistance. While this characteristic somewhat overlaps with the stool shape and form above, particularly in extreme presentations (e.g., pellets, amorphous stools), the focus in this section is on internal structure rather than external appearance.

Normal range

Healthy stool consistency reflects proper water content, microbial balance, and coordinated colonic motility. It supports smooth passage, structural continuity, and complete evacuation without residual sensation.

-

Soft, formed, and pliable. Retains shape while easily deforming during the passage. Corresponds to types 4 and occasionally 5 on the Bristol Stool Scale. Indicates normal hydration, functional fermentation, and intact anorectal sensitivity.

-

Internally cohesive. The stool mass holds together without crumbling, flaking, or disintegrating in water. Leaves minimal residue on toilet tissue and requires minimal wiping.

-

Mildly loose but intact. Softer consistency is acceptable when linked to faster motility, osmotic laxatives, or high water intake. Not pathological in the absence of urgency, bloating, or foul odor.

Abnormal range

Deviations in consistency reflect altered water absorption, fermentation breakdown, or mechanical disruption. These abnormalities often impair evacuation, increase anorectal strain, or reflect early mucosal dysfunction.

-

Hard or compacted. High resistance to deformation. Often associated with delayed transit or excessive water reabsorption. Frequently requires straining and may cause bleeding or pain.

-

Crumbly or brittle. Lacks cohesion and breaks apart on contact. Often linked to prolonged retention, dehydration, or insufficient mucus production. May result in a fragmented passage and incomplete emptying.

-

Loose, mushy, or paste-like. Deforms too easily and lacks internal resistance. May reflect mild inflammation, dysbiosis, or impaired fat binding. Often leaves residue and requires excessive wiping.

-

Oily or visibly greasy. Noted by sheen or oil droplets in the toilet water. Suggests fat malabsorption (steatorrhea) when persistent and unlinked to dietary oils or laxatives.

Stool Odor

The content of the small intestine entering the large intestine, known as chyme, is generally odorless. The volatile smell emitted by stool primarily reflects carbohydrate fermentation, protein putrefaction (rotting), fat oxidation (rancidation), gut bacterial composition, and intestinal transit time.

Volatile compounds are small molecules, mostly gases, produced by bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates, putrefaction of proteins, and oxidation of fats. They include hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, indole, skatole, and various sulfur-based gases, all of which contribute to stool odor.

Indole and scatole are organic compounds that occur naturally in human feces and have an intense fecal odor. But don't laugh − at very low concentrations, both have a flowery smell and are used in many perfumes.

The bulk gases produced during fermentation, such as hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide, are odorless. The smell of flatus, like that of stool, comes from the same trace volatile compounds released during bacterial metabolism.

Trace amounts of alcohol are also produced during fermentation, but they contribute minimally to stool odor compared to sulfur compounds, amines, and phenolic gases.

Putrefaction is the bacterial decomposition of proteins under low-oxygen conditions in the large intestine. Unlike carbohydrate fermentation, which produces mostly odorless gases, putrefaction generates a range of highly odorous compounds.

These include hydrogen sulfide (responsible for the smell of rotten eggs), methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide (sharp, sulfurous gases), ammonia (from nitrogen metabolism), and already mentioned indole and skatole, which give stool its characteristic fecal odor.

These volatile gases are the primary contributors to the unpleasant smell of both stool and flatus. The intensity of odor reflects the degree of protein breakdown, bacterial flora composition, and intestinal transit time.

In certain pathological cases, the odor of stool can take on a distinct and deeply unpleasant quality associated with tissue necrosis. When tumors develop in the rectum or distal colon and begin to ulcerate or outgrow their blood supply, areas of the tumor may undergo necrosis.

The breakdown of this dead tissue, especially in a low-oxygen environment, leads to the release of volatile compounds with a characteristically foul, sweet, and sickly smell. Clinically, this odor has been compared to rotting eggs, decomposing flesh, or drainage from infected wounds.

It is different from the usual offensive odor of stool or flatus — sharper, more persistent, and often accompanied by other signs such as blood, mucus, or incomplete evacuation. While not exclusive to malignancy, the presence of such an odor in stool, especially when recurring and unexplained by diet or infection, requires prompt medical evaluation.

It's a well-established fact that dogs could easily replace fluorograms (lungs), mammograms (breasts), and colonoscopies as first-line diagnostic tools, especially in population screening, given their speed, non-invasiveness, and ability to detect volatile markers of disease long before structural changes become visible on imaging.

The same olfactory diagnostic applies to vaginal, cervical, oral, and certian head and neck cancers. A trained dog can detect abnormalities simply by sniffing a person fully clothed or by evaluating a swab, mask, or pad worn for a few hours. In later stages, the odor may be noticeable to human observers as well.

I’m not making any of this up. A wide range of sniffing devices is in development to detect cancers of the colon, stomach, lungs, breast, oral cavity, cervix, and prostate, among others. Most are still in the research or early clinical phase but already show high sensitivity and specificity, comparable to imaging or biopsy in some early studies.

But I’m getting off-topic. Let’s get back to stool odor.

Normal range

Normal stool odor is unpleasant but not extreme. It reflects a balance between microbial metabolism and digestive completeness.

-

Mild to moderately offensive. The smell is distinct but tolerable, resulting from the breakdown of amino acids and bile pigments by colonic bacteria.

-

Transient and contained. The odor dissipates quickly after flushing and does not linger or permeate the bathroom.

-

Diet-dependent variation. Temporary intensification may follow an increased intake of meat, eggs, cruciferous vegetables, or garlic without indicating pathology.

-

Not accompanied by chemical sharpness. No acrid, sour, or rotting notes that suggest infection or malabsorption.

-

Increased odor with loose stools. Diarrheal stool often smells stronger not due to composition alone but because its increased surface area and water dispersion release more volatile compounds into the air.

Abnormal range

Excessively foul, absent, or unusual odors may reflect microbial imbalance, digestive inefficiency, or underlying disease.

-

Putrid or rotting smell. A strong, persistent odor resembling decomposing tissue may indicate internal bleeding, necrosis, or colorectal tumors. Comparable to the smell of spoiled meat left unrefrigerated.

-

Sour or acidic odor. Common in rapid transit, carbohydrate malabsorption, or during acute diarrhea episodes. Similar to the smell of fermented cabbage or sour milk.

-

Rancid or oily smell. May point to steatorrhea or undigested fat reaching the colon. Often likened to the smell of old frying oil or oxidized butter.

-

Unusually sweet or chemical-like. Occasionally reported in severe dysbiosis or during antibiotic-induced shifts in flora. It may resemble the odor of artificial sweeteners or acetone.

-

Little or no odor. A lack of stool smell may reflect severe dysbiosis or antibiotic use since most stool odor is generated by microbial fermentation.

Stool Buoyancy

This property describes whether the stool floats or sinks in water. It reflects gas content, fat presence, fiber intake, water retention, and overall stool density.

Normal range

-

Sinks slowly or settles neutrally. Typical stool sinks gently or remains near neutral buoyancy. This suggests normal bacterial fermentation, balanced gas production, and adequate hydration and composition.

-

Occasional floating. It can result from temporary increases in gas (from fermentation), high-fiber foods, or mild fat malabsorption. Common after abrupt dietary changes or the introduction of prebiotics or probiotics.

Abnormal range

-

Persistent floating with oily residue. Suggests significant fat malabsorption. Common causes include pancreatic insufficiency, bile acid deficiency, celiac disease, or chronic small intestinal infections. This stool may appear pale, bulky, and leave an oily film on the water.

-

Rapid sinking and compact. Indicates unusually dense stool, possibly due to dehydration, low salt intake, inefficient protein digestion, or reduced fermentation. Seen in cases of dysbiosis or high-protein, low-carb, low-salt diets.

-

Erratic or mixed buoyancy. Alternating floaters and sinkers may indicate segmented or impacted stool. The initial portions are often drier and denser than the later parts.

Stool Surface Texture

Describes the visible and tactile outer structure of the stool’s surface, often reflecting hydration, salt deficiency, dietary content, bacterial activity, and motility.

Normal range

-

Smooth. A uniform, soft outer surface indicates balanced hydration and well-formed stool. Most typical in diets with adequate fat, fiber, and water.

-

Slightly cracked. Mild superficial cracking or patterning may be normal, especially with slower transit. Indicates some water reabsorption in the colon without pathological dehydration.

-

Matte or lightly coated. A thin natural film on the surface may result from mucus, fat, or bacteria. Considered normal if color and consistency are otherwise within range.

Abnormal range

-

Rough or dry. A coarse, uneven texture suggests insufficient moisture, excessive fiber, or prolonged retention in the colon. Often associated with straining, hard stools, incomplete emptying, and latent constipation.

-

Deep cracks or fissures. It can indicate latent constipation, excessive dehydration, and salt deficiency. These stools are often dense, harder to pass, and may cause anorectal trauma.

-

Mucus-coated. A visible, clear, or white, slimy layer may reflect irritation, inflammation, or infection. It may also occur in IBS, proctitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or colorectal tumors.

-

Greasy or slick. A shiny, oily surface may indicate fat malabsorption, especially if accompanied by floating stools or oily residue in the bowl.

-

Foamy or bubbly. May indicate fermentation, dysbiosis, or excessive gas. Uncommon in well-formed stool, more often seen in loose or unformed types.

Stool Homogeneity

This parameter refers to the internal uniformity of the stool in terms of color, texture, and content. Homogeneous stool reflects effective digestion and absorption.

Normal range

-

Even texture and color throughout. Indicates complete digestion, proper enzymatic activity, and balanced microbiota. No visible residue, layers, or fragments.

-

Occasional specks or small inclusions. Undigested skins and seeds of fruits and vegetables may appear in the stool. In moderate amounts, these inclusions are benign. When consumed in larger quantities, they may obstruct the appendix, trigger appendicitis, and require surgical removal. Over 300,000 cases occur annually in the U.S. alone.

The peak incidence of appendicitis is seen in late childhood and early adolescence. Transient obstruction may no longer be visible by the time surgery is performed, and the connection with skins and seeds I mentioned is considered controversial. My counterpoint is: what else could explain such a high incidence of appendicitis in otherwise healthy children?

Notably, removing skins and seeds from fruits before offering them to young children it's a common practice in most of Europe. That's how I remember my childhood, and, probably, how I was spared appendicitis. My wife was less lucky, and her appendix was removed when she was around 6 years old. The surgeon found a few cherry pits and hard skins of roasted sunflower seeds inside her appendix.

In adults, the more likely cause of appendicitis is chronic or latent constipation that allows solidified feces to obstruct the narrow entrance of the appendix, which is attached to the cecum, the first section of the large intestine. Under normal conditions, the fluid consistency of cecal contents prevents such blockage.

Abnormal range

-

Heterogeneous or layered. Clear differences between outer and inner parts may reflect incomplete mixing, rapid colonic transit, or stool retention. Suggests fecal impaction and latent constipation.

-

Visible undigested food particles. Suggests poor mastication, fast transit, enzyme deficiency, or pancreatic or biliary dysfunction. Common in individuals with low stomach acid or after consuming poorly chewed high-residue foods.

-

Mixed consistency. A single stool with both hard and mushy sections may indicate inconsistent motility, partial impaction, or erratic colonic contractions.

Stool Residue

This property refers to visible streaks, smears, or oily films left behind in the toilet bowl or on toilet paper after wiping. It reflects fat content, mucus secretion, and stool consistency.

Normal range

-

Minimal residue. A well-formed, properly hydrated stool typically leaves little to no streaking on the toilet bowl and requires only moderate wiping. Indicates effective digestion, balanced hydration, and absence of excess fat or mucus.

Abnormal range

-

Greasy or oily residue. A slick film on the water surface or oily smears on the bowl suggest fat malabsorption. Often associated with a floating stool and pale color. Common causes include pancreatic insufficiency, bile salt deficiency, and intestinal infections.

-

Mucus streaks. Clear or whitish sticky residue on the bowl or tissue may reflect irritation or inflammation of the lower colon or rectum. Common in irritable bowel syndrome, proctitis, infections, or inflammatory bowel disease.

When mucus streaks on the toilet paper contain small droplets of blood, this pattern is typical of a colorectal tumor. I avoid calling it cancer since some tumors are benign. Regardless, if this mostly asymptomatic condition appears, you must see a GI physician without delay.

This concludes my list of qualitative (quality-related) observational parameters of your stool and your children's. It doesn't apply to pets because the structure, color, and consistency of their stools differ significantly from humans.

Although I've been an obsessive parent to two dogs and two cats for most of my adult life, they were perfectly healthy digestion-wise, so I have zero experience in pet crapology.

How to overcome functional, latent, or organic constipation by "normalizing" stools

Constipation rarely happens out of the blue in otherwise healthy adults. It is usually preceded by decades of semi-regular stools that are either too large, too hard, or both. These abnormal stools cause gradual nerve damage and enlargement of the colon, rectum, and hemorrhoidal pads until one day, the bowels refuse to move as was meant by nature — once or twice daily, usually after a meal, and with zero effort or notice. Therefore, it's best to recognize and eliminate abnormal stools long before they bite you in the butt, literally and figuratively.

To attain small stools and effortless bowel movements immediately— use the Hydro-CM program. The duration depends on the degree of acquired colorectal damage. The goal is to eliminate straining, reduce pressure on internal hemorrhoids, and restore anorectal sensitivity.

For a comprehensive, life-long recovery, start from this section: No Downside, Just Upside-down.

Takeaways

Stool observation is a lost but valuable skill. It can reveal more about your digestion than most lab tests or procedures, without cost or discomfort. Here are the main takeaways from the preceding discussion:

-

You don't need special training to notice major deviations. Color, odor, consistency, and surface changes are easy to spot if you know what to look for.

-

The odor is often more revealing than appearance when it comes to serious issues. Don't ignore it.

-

Most abnormalities reflect common, manageable issues: wrong diet, inadequate chewing, salt deficiency, or disrupted bacterial flora.

-

Persistent changes, especially those involving bleeding, mucus, odor shifts, or floating oily stools, require medical evaluation.

-

The biggest red flag is a new, recurring change in your baseline pattern that has no obvious cause. Don't wait and hope it goes away.

-

Doctors may dismiss stool observation as primitive, but that's shortsighted. Once you know what to look for, a single glance into the toilet bowl may save your life.

Author's Note

How do I know so much about stools? Well, I've observed mine at least 25,000 times throughout my long life. Humor aside, I am not a stool auteur or carnal deviant, so don't ask me to check the photo of yours. This subject is well-studied in clinical literature, and that's what's been on my desk since I entered medical university in 1972.

If you'd like to learn more or go in-depth on anything discussed in this article, here are some of the core sources I recommend:

-

Rome IV Criteria for Functional Bowel Disorders – the international standard diagnostic framework for IBS and related conditions (theromefoundation.org)

-

Bristol Stool Form Scale and validation studies – the basis for clinical stool classification (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

-

Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease – foundational GI textbook (Amazon.com)

-

Yamada's Textbook of Gastroenterology — same as above (Amazon.com)

-

Guidelines from the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) – especially regarding stool analysis and pediatric bowel health (espghan.info)

-

Stool analysis laboratory protocols – tests such as fecal occult blood, stool fat, pH, and differentiation between osmotic vs. secretory diarrhea. (Fullscript Academy)

-

Clinical observation standards. Used in clinical settings to check stool consistency, odor, appearance, mucus, and fat content. (Karger International)

All of these references are part of standard medical training. The only difference is that most doctors don't spend their careers studying them after cramming for finals. I did because colorectal disorders have been a central focus of my books and research for the past 25 years.

If the information in this article reaches even a small portion of millions of people who struggle with chronic colorectal disorders, it may prevent tens of thousands of avoidable surgeries, delayed diagnoses, and mismanaged conditions. Many of the worst outcomes, such as colorectal cancer, severe hemorrhoids, diverticular disease, appendicitis, and other irreversible bowel damages, begin with visible signs in the toilet bowl but go unnoticed or ignored.

Whether this work saves one life or hundreds of thousands depends not only on my writing about this topic but also on what you do with it. If you found this article useful, please share it with your family and friends to support my work!

Thank you!

Konstantin Monastyrsky